Spring Bloom in Saguaro National Park

I was enthralled with a visit to Saguaro National Park in the spring. I had never seen the desert before and the flowers were breath-taking. I felt very lucky to bear witness.

Essence of Nature

In the last several months, I have been exploring minimalism as a way of projection and abstraction in my photography. The simplicity of minimalism reduces nature to its essence to reveal the underlying beauty of structure and form. These three images were made while hiking trails in the Sonoran Desert.

Dragonfly Out in the Sun

Hold On To Me,

Sunlit Beauty,

and Rose Petals and Golden Wings

Despair Paintings

The world seems to carry on as if there aren’t a million reasons to be shocked. But because I don’t want to go numb, I try to paint them, at least a few. For these, I paint figuratively, as I was trained, even though now, often, my desires, and my output, is abstract. Still, how can we ignore the drought in Afghanistan, the strife in Sudan, the war in Gaza, the invasion of Ukraine? Or even what goes on in our own lives?

Finding a Pathway

As an emerging artist, the art form I work with is primarily abstract painting and large-scale installations. My artistic process involves using various mediums and techniques to create physical manifestations of internal dialogues and personal judgments. In my abstract paintings, I use house paint, various tools, and textured canvases. The technique involves creating overconfident brushstrokes that mask my imposter syndrome, with multiple layers of paint partially hidden under the surface. The inner turmoil arising from self-doubt is expressed as geometric shapes woven together with texture.

Wholeness Through Fracture: Sculpting the Human Condition

Three works in clay by Aleksandra Scepanovic.

Each of these works tells a story of the complexity and beauty found in life’s fractures, embracing the wholeness that emerges through resilience.

Coastal Grey

This series of photographs, titled “Coastal Grey,” depicts elements of summer themes. My goal was to capture a vibrant setting and allow the viewer to realize it remains vibrant even though color is lacking.

Symphony in Green

I paint landscapes, interiors, exteriors, still life’s with figures interacting and posing for the camera displaying memorable moments with families, friends, and neighbors.

Friends, Triplets, and Family Narrative

Tianyagenv uses light clay to make miniature figures and wishes to capture the characteristics of femininity, vulnerability, and resilience in potential.

Green Canyon Bridge 1993, Thrive, and Tarot Deck: The Moon

My paintings explore the abstract simplicity of ordinary life and the deductive impulse to see ourselves reflected back in art.

Metamorphosis

The photographs are from the series, Metamorphosis. Each painterly creation constructed from dozens of layered photographs is driven by my reaction to nature’s extreme seasonal change.

Les Femmes Mondiales Black and White

Les Femmes Mondiales Black and White

Hurricane

Chicago Ice

Three Photographs

UNDER THE PIER, MALIBU CA

SUNSET OVER THE PACIFIC

and POOL, POST RANCH INN, BIG SUR

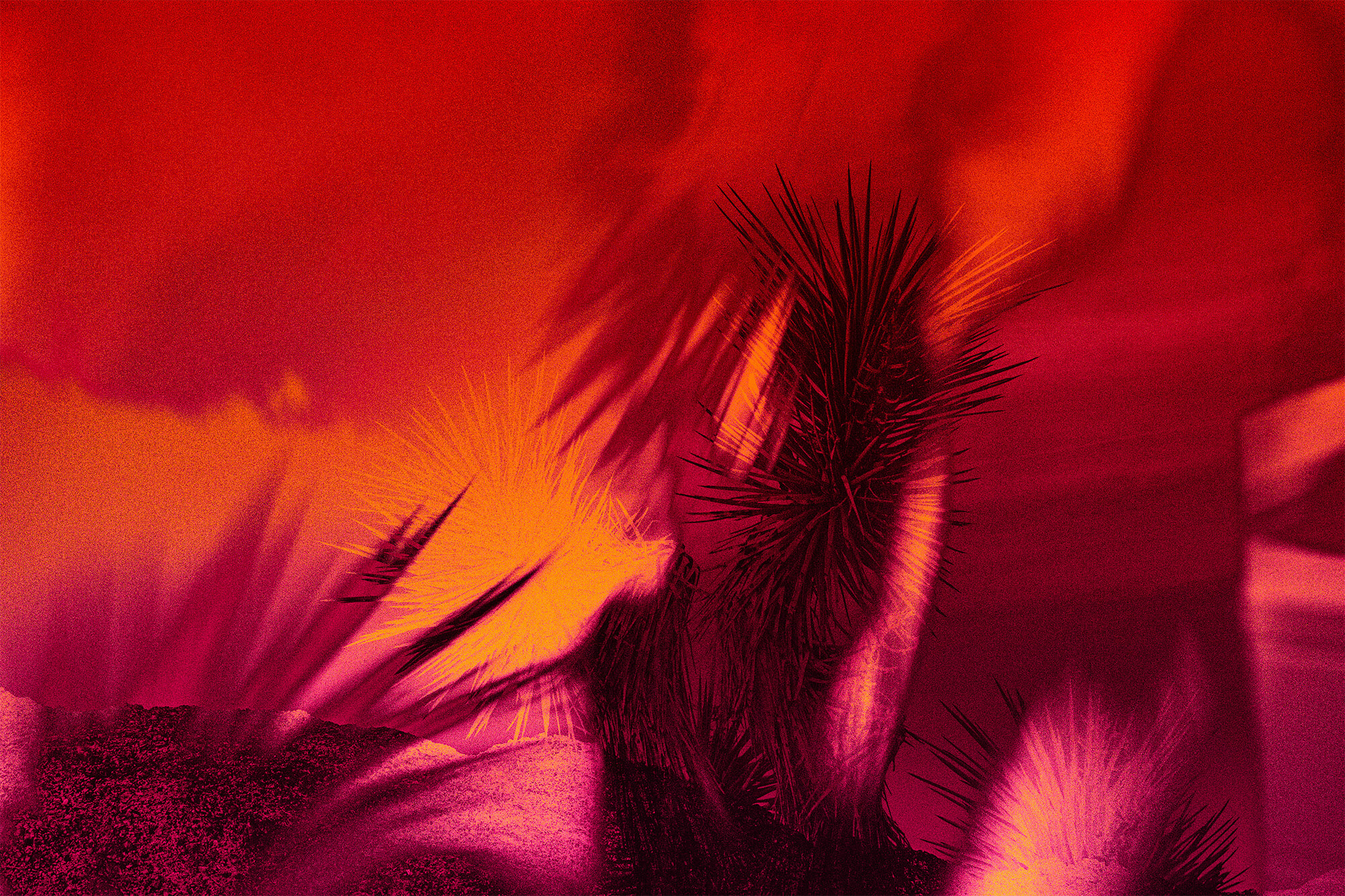

Joshua Tree Project

The images are part of a larger series created in the Mojave Desert around Joshua Tree in the fall of 2023 that explore the shifting state of the desert.

Chasing Paradise

This series, Chasing Paradise, draws upon my work as a fine artist in painting, as I create stylized photographs of flowers and plants found in my rural environment.

Ocean Sleep and Turtle Light

Turtle Light and Ocean Sleep are works of multimedia and sculpture mediums, respectively, depicting the natural world with fantastical elements.