Photo by Hasan Almasi on Unsplash

Synopsis

When a "snitch" accuses a homeless man of the murder of a Bronx police officer, lives are disrupted, and justice is fleeting for all persons involved.

Some say that Rikers Island is the largest penal colony in the world, and that contention is difficult to confirm or refute. The New York City jail complex may hold more prisoners than the gulags of the Soviet Union, but perhaps less than the re-education camps of the People’s Republic of China. Nobody has tried to count all the bodies.

Geographically, Rikers likely occupies more acreage than the torture chambers of Syria, but it is smaller in size than Robben Island, another notorious tract of land surrounded by water, with which it shares part of a name, and a geographic designation. Unlike Robben Island, Rikers Island holds male and female prisoners and never served as a leper colony. It was a city garbage dump until 1934, when architect and “master builder” Robert Moses ordered that the accumulated refuse be relocated to Staten Island. He didn’t want the unsightly, smoldering effluvium to mar the view from the upcoming 1939 World’s Fair, held across the East River and Flushing Bay, at a site in Queens. After its prodigious rat population was nearly exterminated, a by-product of its time as a landfill, the city built a jail complex on the island. Today, ten thousand men and women are locked up on Rikers and more than three-quarters of them have not been convicted of a crime. Most of those men and women are Black and Brown and poor.

Jails tend to be more frenetic than prisons. The men and women housed there are awaiting trial or transfer to a state facility, or are serving sentences of one year or less. Training and educational programs are mostly absent. Criminologists have found that jail inmates are not yet “institutionalized,” and disciplinary infractions are more common than in a prison. Similarly, a Bronx judge once opined that offenders need to “marinate” in the unique brine of Rikers before they accepted the reality of a prison sentence and the collateral damage that such a sentence brings to them, their loved ones, and society as a whole. In other words, in jails, many guys are bugging out, acting out and trippin’, and engaging in mayhem in all its varieties as they come to grips with the loss of their freedom and the other deprivations that come with a prison bid. Some short-termers simply resist being placed in a cage, a reasonable human reaction to such a circumstance.

The thing about men’s prisons or large urban jails like Rikers Island is they’re never quiet. Gates slam shut. Feet shuffle. Metal clangs. Voices murmur. Bodies toss and turn. There are sighs and shouts and cries, sobs and shrieks. Men scream. Flesh pounds flesh. Piss streams into stainless steel commodes. Farts crack like thunder. And, for some reason, the sound of an actual thunderstorm in a large jail or prison is scary as shit. The thunder booms and the lightening crackles as though the world was coming to an end. God is getting warmed up for the devastation that is about to erupt.

The noise is both collective and individual; it comes from everywhere and from nowhere at the same time, along tiers and on blocks, in corridors and in open spaces, during all hours of the day, and through the night. The sounds are both natural and unnatural. They include the sounds of hundreds of men inhaling and exhaling in the early hours of the morning, some who are asleep, and some who are not. The sounds of machines buzz and hum and thump. The thrum of that machinery is constant and without end, and there is no respite from the pervasive institutional noises that inhabit every corner of the jail and the brain of every man who lives or works there. It is insidious. But the noise and the sound and the fury does not drown out the thoughts of men, who try to imagine that they are somewhere else. The sound reminds them of where they are, and who they are, like a sailor who still feels the pulse of the sea, even when he walks on concrete.

All of that noise churned around in Javan Patterson’s head, as if his brain were a garbage disposal, the swirling mess mixed with his own, random thoughts, that came and went without order or direction. Sometimes, he thought he would never eat again, that his stomach had shriveled up, and it was simply taking up space, made useless by his lack of appetite. Sometimes, he felt hungry. At other times, he felt hot or even cold, despite the oppressive heat in his cell, and the lack of air conditioning or even air that circulated. He felt lonely. He felt alone. Sometimes he felt as though his legs didn’t work, but he couldn’t remember if this was part of a dream or if somehow his legs had really atrophied, succumbing to the general inactivity that marked the almost twenty-three hours a day he spent in his solitary cell. Then, he would swing his legs over the metal plank he slept on, plant his feet on the ground and stand, the earth beneath his feet, reassuring him that everything was working okay. This was comforting, even though he knew, if he leveled with himself, that his feet weren’t really touching the earth and things were, in general, definitely not okay.

He didn’t talk to other men in protective custody, but some guys in here tried to talk to him. In response, Javan just nodded his head. He didn’t want to encourage anyone. One guy said that the key to surviving the bing was discipline of the body and the mind. Pace your cell to keep the blood circulating. Do sit-ups and push-ups. Grab a book from the library cart when it made the rounds. Stimulate your brain. Some of the volunteers who pushed the cart along the block were friendlier than others and could recommend a book. Javan didn’t bother to tell anyone that he couldn’t read. He lacked the energy to explain and respond to the questions such an admission provoked. Most of the time, he stared at the filthy white walls of his cell and tried not to bang his head on the toilet, which sat inches from his face, when he tossed and turned in the night or when he lifted himself from his bed.

The man in the cell next to him was a Black Hebrew, named Yaakov Ben-Yahweh. Before dawn, Ben-Yahweh would start the day with a benediction that he shouted out to the tier. He listed the names of Black and Brown folk killed in New York City – Yusuf Hawkins, Gavin Cato, Ernest Sayon, Nicholas Heyward, Jr., Eleanor Bumpurs, Michael Griffith, Michael Stewart – and asked the other inmates to join him in a prayer to bless their memories. The police had killed many of them. Javan thought that the list of names grew longer every day.

“Ain’t no concrete or stone to their memories,” Ben-Yahweh preached to his reluctant congregants. “Just dead flowers mark the spot where they passed.”

In response, the other men in p.c. yelled and cursed him down. When he acted especially vocal or unruly, the c.o.s threatened to cut his dreadlocks, which reached down to the middle of his back. They were worried Ben-Yahweh’s daily jeremiad would inadvertently start a riot. Mostly because the other men wished that he would shut the fuck up. Ben-Yahweh was a voluble person and he continually tried to engage with Javan, who never responded to his queries.

The routine was always the same. The Black Hebrew’s voice rang out over the tier.

“How you doing today, young blood? Keeping your head up?”

Javan listened but said nothing.

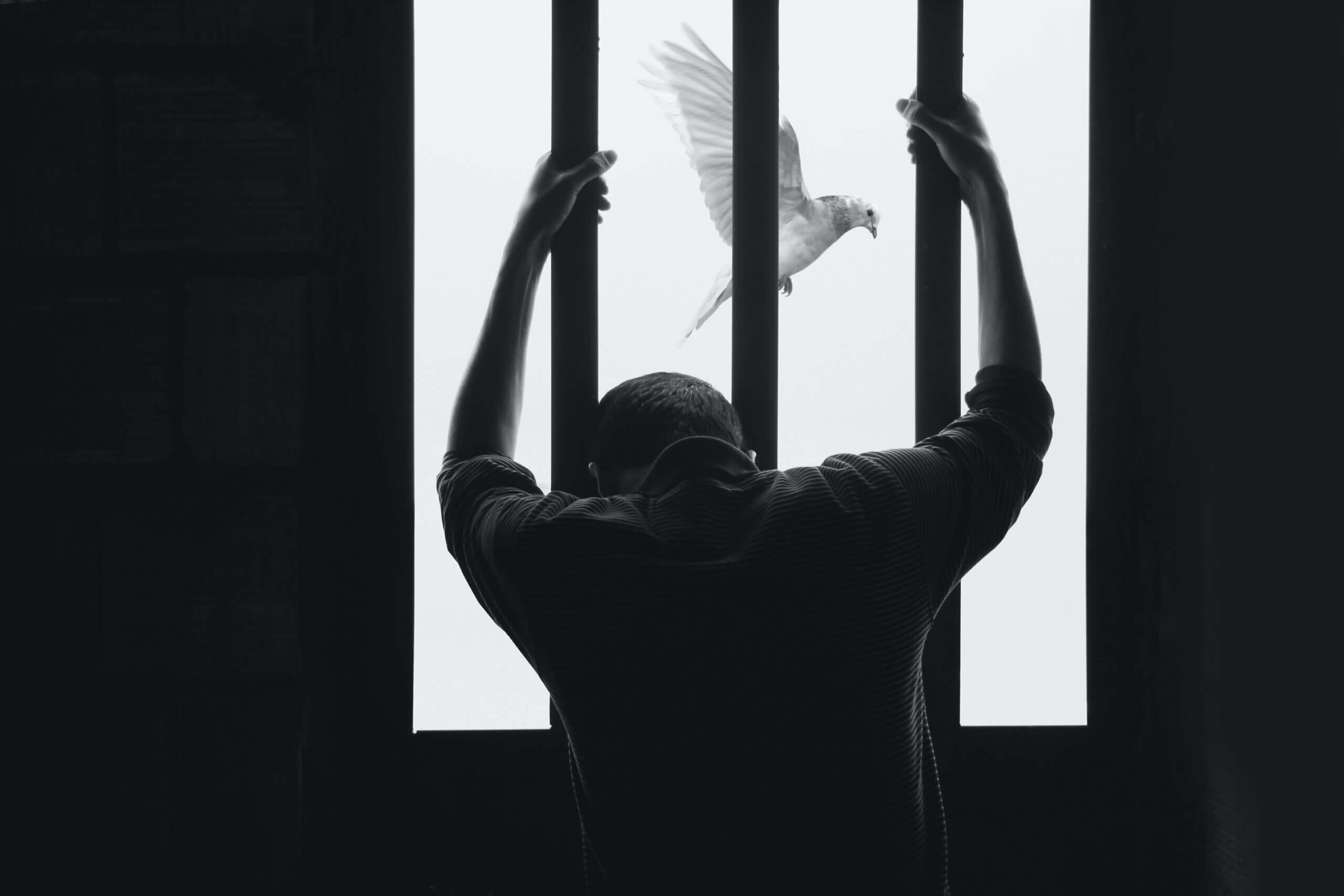

“Remember my brother, they can put a man’s body in a steel cage but they can’t keep his mind from flying away.”

This was Ben-Yahweh’s favorite saying. The only time Javan missed hearing it was when officers woke him at 4:00 a.m. to transport him to the courthouse and he was gone before his neighbor awoke.

Javan had never been in jail for more than two or three days. When cops arrested him, it was almost like a game, with carefully orchestrated rules that each side was hesitant to break. If uniforms saw him pushing his shopping cart, they usually stopped their patrol car, exited the vehicle and asked him a few questions. He made sure to keep his hands still, in front of his body and not make any sudden movements. He presented his wrists, the cops slapped on the bracelets and placed him in the car for the ride back to the precinct. Sometimes, while he sat in the cruiser, the uniforms debated about what to do with him. It was disconcerting to be the subject of their discussion with no vote on the outcome of his fate. He sat in the car, his wrists cuffed behind his back, his body hunched forward, and he stared out the window and waited. In the winter, when the heat blasted from the car’s air vents, he thawed out.

If they decided to arrest him, he often spent a couple of hours in a holding cell. He was then transported to Central Booking in the Bronx Criminal Courthouse, where he waited for his court appearance. Occasionally, he was released from Central Booking without seeing a judge. Usually, he was released a few hours after his court appearance, sometimes even from the front doors of the courthouse itself. This routine repeated itself every couple of weeks, but it lacked vigor. To the cops, it was mostly inconsequential, banal even. The arrest, the paper work, the incarceration, the constitutional rights, the cost, the deprivation of liberty, the bull pens, the jail cells, the criminal record, the humiliation, the emotional distress, the fear, the pain, all reduced to afterthoughts or even no thoughts, by routine and common occurrence. Cops got more hyped when they had bigger fish to fry. To them, Javan was a minnow in a sea teeming with sharks.

Javan knew many of the cops who arrested him by name. There were Murphy and Perez, who apologized when they hauled him away. Perez bought him pretzels from the precinct snack machine and Murphy cracked jokes, telling Javan that one day he’d be rich from selling his junk, but that it was probably easier to buy a Lotto ticket. Collins and Stanton were humorless, by-the-book hard-asses who cursed at him and always tightened the handcuffs until his wrists hurt. When Stanton stuffed him into the RMP, he made sure he banged Javan’s head on the door every time, as if the arrest itself was an affront. That man was always angry. Fitzgerald and Harris sometimes commandeered his shopping cart but usually let him go, especially if it was late in their tour. Javan knew they religiously avoided the paperwork necessitated by a collar.

Tompkins and Rashad, the latter the only female cop he regularly encountered, always called Javan’s mom and let her visit him in the precinct bull pen before he went to Central Booking. Rashad comforted his mother and reassured her every time that her son would be released before the new day dawned. Rashad also bought him snacks from the vending machine, but, for some reason, she preferred potato chips to pretzels. Sometimes, when he saw Rashad on the street, she asked him how he was doing and offered to buy him a coffee, especially on a cold night.

Javan didn’t start to worry about his case until his Supreme Court arraignment. When the court officers escorted him through a door behind the judge’s bench and into the courtroom, he noticed that it was much larger than any he had ever seen before and it smelled musty and damp. Dappled light seeped in through the high, vertical windows. The walls were paneled with dark wood and the judge’s bench sat on an elevated platform, like the altar in a church. Police officers packed the audience, many of them in uniform, some wearing their shields on chains around their necks and over their street clothes. It looked like hundreds of them were there, more cops than he had ever seen in his life. When he plodded in, his leg irons jangling along with his footsteps, they stopped talking and sat up. Their pale necks snapped to attention. In unison, they puffed out their chests and held their shoulders erect, every eye focused on him and the doings at the bench.

Javan noticed that the prosecutor was speaking with a woman sitting in the front row, who was about the age of his brother. She was white, with short blonde hair and an upturned nose. Deep, dark circles framed her eyes, which were a luminous blue and wet. Makeup streaked her cheeks, as if she had held her face up to the sky and it had been washed by the rain. When he shuffled to the defense table, their eyes met for a moment, but Javan looked away first. He couldn’t hold her gaze. Her eyes possessed a strange light that seemed electric. She registered shock when she first saw him. If his hands were free and he stretched out his body, he would have leaned over the railing and touched her, fingertip to fingertip, in solemn recognition of the tragedy that had befallen them both. He wanted to tell her that he was sorry, that he was there because of a mistake and that this mistake was cataclysmic for her, too. He wanted to offer to help, to set everything straight.

Out of the corner of his eye, Javan saw that her surprise turned to anger. Some of the cops sitting around her stared him down. He could feel their eyes bore into him. They were angry, too, and no amount of explaining would soothe the anger and the hatred that he felt in the courtroom. They wanted his head. He was sure of this. There was a seething energy present in the room that felt poisonous, as if he had overturned a rock, and exposed the creatures underneath it to the sun. This realization made him sad, but in a strange way, it gave him a clarity of mind that had eluded him until now. He realized that the manner and time of his death was something over which he still had control. He may have lost almost everything, but he still had that.