Synopsis

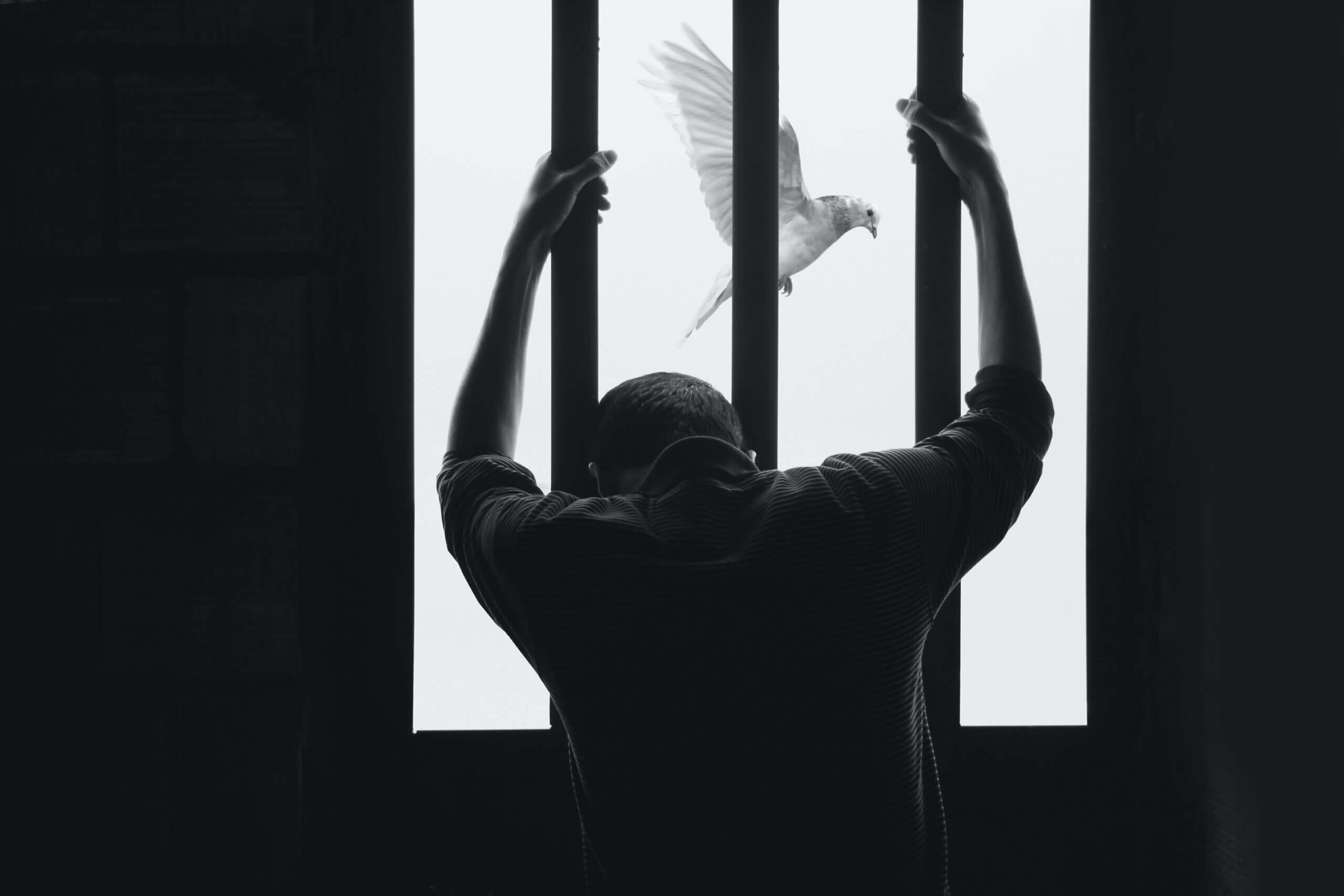

When a "snitch" accuses a homeless man of the murder of a Bronx police officer, lives are disrupted, and justice is fleeting for all persons involved.

Mary

It was dark when the alarm went off. Mary Patterson lifted herself from bed, splashed cold water on her face, brushed her teeth, then dressed in the clothes she had laid out on the chair the night before. She wore a dark blue dress, something that she had worn to church on many occasions, and flat shoes. She listened to the news on the radio as she got ready, and opted for stockings, despite the predicted heat, but she ultimately rejected the idea of a hat. She packed her bag and allowed herself one sip of coffee. (She was worried she would have to pee at an inopportune moment on her journey.) Then, Mary Patterson rode an elevator down to the lobby and walked out into the cool dawn air.

By the time she exited the apartment building, the moon had faded into the firmament and, to the east, first light peeked up over the horizon, smudged stripes of yellow, orange and purple, the sun partially obscured by thin clouds, molten in the morning sky. The air still felt clean and comfortable.

Mary Patterson turned left on 138th Street and walked down the steps to the subway. She waited on the platform for a Number 6 train and rode it to 59th Street and Lexington Avenue, in Manhattan. She disembarked from the train, trudged up the steps of the station and across the upper-level concourse and transferred to an R train. That train carried her to Jackson Avenue and 42nd Road, in Queens. Once there, she exited the station and walked over to Jackson Avenue to catch the Q100 bus. She waited at the stop for fifteen minutes, during which time mothers, fathers, girlfriends and boyfriends, and children, joined her on line for the next stage of her ride. The sun hung low in the sky, just above the taller buildings on Jackson Avenue, smoldering the oxygen out of the air. There was no shade at the bus stop and Mary Patterson could feel the sweat begin to trickle down her forehead and the back of her dress.

A dark-colored dress was a poor fashion choice for summer in the city, but no matter. She looked neat and proper and impressions mattered if she was to avoid some of the routine humiliations that were a feature of the place she had arisen so early to visit. Most were respectful. After all, the C.O.s had mothers, but you never knew. When Mary passed through security at the jail, some of the officers who interrogated her or patted her down, were most certainly mothers themselves. She could tell. They treated her with respect and with dignity and when their eyes met hers, the women would give her a slight head nod or a rueful smile or a gentle pat on the back. She had too many lines on her face and grey in her hair to be somebody’s girlfriend. And these women just knew.

The trip had now become routine, almost routine, she corrected herself, and she had saved enough vacation and sick days to endure it as often as she could. Her bosses at the sorting facility where she worked did not reproach her for using her time. They had children, too, and many of them had grown up on the same streets and experienced the same challenges, the same fears, as she had with both of her boys. Besides, they knew her as a good and kind and reliable worker, with nearly twenty years at the Postal Service, one who never tarried and whose absence before this was infrequent enough to be remarked upon by all who knew and worked with her.

Mary Patterson boarded the Q100 bus. She shared a seat with a young woman holding a baby, who was swaddled and quiet during the trip. In twenty-five minutes, the bus made eight stops and by the time it reached Hazen Street and the bridge, every seat was taken, a jumbled mass of mostly women and small children, many of whom were sleepy but fitful in their comportment. Mary Patterson stared out the bus window and counted down the stops, which she had now committed to memory.

Once, a Jewish man who worked with her at the Postal Service told Mary about a game called Jewish Geography. It was a silly and innocuous thing but at the same time, a way for strangers to build rapport, their mutual acquaintances forming a primal connection in a disparate and hostile world. She noticed that in church, when the service was over and members mingled and caught up with each other after another week had passed, people there played a version of this game, too, even if they didn’t know it. Coxsackie, Gowanda, Ogdensburg, Shawangunk, Wallkill, Sing-Sing, the place names from a child’s rhyme, that sounded nonsensical, and knotted your tongue when you said them quickly. Hale Creek, Lakeview, Riverview, Great Meadow, Green Haven, idyllic places, for a picnic by the water or, nestled beside lush, verdant hills, fragrant with spring. Attica, Albion, Altona, Elmira, in another story, places of legend, inhabited by upright knights and ladies, dragons and ogres, quests and battles, on behalf of gods and men. White folks’ business. In different stories, the stories that Mary heard on Sundays, the human geography of the Bronx was reduced to the names of correctional institutions, stops along the way to adulthood, places from which some children never returned.

Shaw-an-gunk. The Dutch bastardized the Lenape word schawan and used the name for a colonial hamlet they established in what became Ulster County. The word meant “in the smoky air,” and was inspired by the mist that settled over the quartz mountain ridge north of the town. In 1986, New York State opened a namesake maximum-security prison there to join others already in the area.

Mary had never traveled to Shawangunk or any other state prison. Before Javan’s arrest, she had never been to Rikers Island because Javan had never been sent there. She had once visited him at the Bronx House of Detention, but that was located on River Avenue, south of Yankee Stadium and a short trip from her apartment.

By the time the bus arrived at the Rikers Island bridge, the sun was high in the sky, the passengers dulled by the heat, the inside like a tin can baking on the asphalt. The passengers exited the bus and formed two lines, one for women and one for men. A school bus, painted the red and blue colors of the New York City Department of Corrections, sat idling at the entrance to the bridge. Next to the bus was a large blue, plastic garbage can. A uniform officer stood alongside the can and shouted at the passengers.

“Last call for contraband.” He pointed to the corrections bus. “Once you on, if you hold any contraband, you will be arrested and you will not see your loved one. You will spend the night in jail. Charges will be filed against you.”

The night before her first trip, Mary Patterson studied the New York City Department of Corrections Handbook for Family and Friends of DOC Offenders. She learned that contraband items included alcohol, drugs, drug paraphernalia, guns, knives, explosives, pagers, cigarettes, cameras, recording devices, two-way radios, money, medications, toys, stuffed animals, nude photos, postage stamps, toiletries, food, implements of escape, attire displaying obscene/offensive, derogatory language or drawings or promoting illegal activity, including but not limited to gang colors or other clothing that commonly signified gang affiliation. (Red? Blue? Pink? White? It was hard to tell. The pedestrian had somehow become sinister.) In addition, visitors were prohibited from wearing see-through or sheer clothing or clothing that exposed bare midriffs or backs, plunging necklines, short skirts or athletic shorts, mid-thigh length, low tops or backless tops or dresses, or bathing suits, although Mary Patterson had yet to see someone wearing a bathing suit on one of her trips to the island. (A bathing suit?) She had once observed a corrections officer examine the length of a young woman’s skirt with a tape measure, the woman and the child she was holding sobbing uncontrollably while they awaited the verdict.

At the head of each line was a female officer and a male officer, holding a metal detecting wand that they used to sweep over the bodies of passengers who wished to enter the corrections bus. From time to time the wand squawked and the object of its grousing was forced to search his or her body for errant metal, sometimes located in hairpins or bra straps, or stray coins, or even something whose source seemed to stupefy both the officer and the wand’s victim. For those select few, a strip search behind what looked like a shower curtain was the only alternative if the visitor wanted to make it over the bridge.

When she finally boarded the bus, Mary Patterson recognized the driver as the same man who had ferried the visitors over the bridge each time she had traveled to Rikers. His beard was long and unkempt and decorated with the remains from breakfast, the pallor of his skin like putty that had sat in the sun too long, his eyes practically weeping blood, his nose aggressively off-kilter. The nose of a pug. The nose of a guy who liked to mix it up and then brag about it. He gripped the stick of the bus’s accordion door like an oar, his elbow cocked as if he was going to row his charges over the bridge. As they climbed up the steps, he exhorted his passengers to hurry, his voice bubbling up from his chest, thick with smoke.

“Let’s go people. No dallying. I ain’t got all day.”

They didn’t dally. They lifted themselves up the wide steps of the bus, their voices muted, their emotions buried, and sat. Hazen Street. The last leg of the journey, no one lost behind the shower curtain, the island just over the bridge, the jail complex glistening in the noon-day light, the bars and the cages and the barbed wire momentarily obscured by the sun and the evanescent joy of those who had come to visit the people whom they loved, still.