Synopsis

When a "snitch" accuses a homeless man of the murder of a Bronx police officer, lives are disrupted, and justice is fleeting for all persons involved.

Kelly

Kelly couldn’t remember the last time she drove a car. She didn’t take the driving test until she was in law school and she had nearly failed it. Now, she was on the far eastside of Harlem at a cut-rate car rental place that looked more like a chop shop than a legitimate business. A friend had recommended it. She sat in the driver’s seat of a small, battered car and listened to the attendant explain its basic functions. The only vehicle available was a subcompact with a stick shift. What was a subcompact anyway? The car most likely to get crushed by a tractor trailer? The price was right and she was passably competent with a stick. She hoped that her driving skills, or what little driving skills she once had, would come back to her as soon as she got on the road.

“You sure everything is okay with the paperwork?” she asked the attendant. She envisioned being pulled over by a New York State Trooper and forced to explain why she, an officer of the court, hadn’t bothered to check that the registration was valid and that the VIN number on the car matched the paperwork.

“Totally legit.”

The guy seemed insulted that she asked. He leaned in and popped open the glove box, brushing Kelly’s shoulder and forcing her to press back against the bucket seat. He smelled like sweat and gasoline. The attendant pointed to a sheaf of papers inside. They looked crumpled and greasy and they didn’t inspire confidence. Kelly fought the urge to pull them out and review them with a magnifying glass.

The attendant walked back to his office. Kelly balanced her foot on the brake and pressed down on the clutch. She shifted the car into first gear and leaned on the gas. The tires squealed and the transmission made a grinding noise. She smelled burning rubber. Panicked, her right hand banged against the steering column. Water sprayed the windshield, the wipers squeaked several times, and then stopped. Kelly looked around the garage. The attendant jogged over to the car and opened the driver’s side door. He pointed to a lever on the floor, to the left of her seat.

“The parking brake is on. You gotta use it on hills and shit.”

Kelly scanned the garage. “It’s flat in here.”

“It’s like a precaution.” The attendant grinned. “You know. Safety first.” He pointed to a sign hanging above his office door. It read “We Have Worked ‘0’ Days Without A Lost Time Accident.”

He showed Kelly how to release the brake and then he made her do it. She popped the button, lowered the lever and maneuvered the car out of the garage and onto 102nd Street. Then she headed east, to get on to the FDR Drive. She felt relieved when she made it to First Avenue. She eased the car onto the highway and rolled down her window. The air was damp but the breeze felt cool and it helped assuage her anxiety. The sun was still low over the sky. As she entered the traffic, it sat just above the Harlem River, and cast an orange glow over the water. She passed the Ward’s Island Bridge on her right, then a barge, pulled upriver by a dingy tugboat. It was stacked with steel drums, and their sides, slick with dew, glistened in the early morning light. Kelly cruised past the boats and when she hit the New York Thruway, the traffic thinned, she picked up speed, and her body began to relax.

For the drive, she had packed a CD wallet and placed it on the front passenger seat. Now, she leaned over and pulled out a random CD and pushed it into the player. When the song began to play, she heard a snaky guitar line and then a horn section kicked in. She could tell right away it was “Vampin,” the first cut on the album The Mack, by Willie Hutch. It was one of her dad’s favorites. When Kelly was a child, her father played the album all the time. When the third track from the record came on, “I Choose You,” he would dance around the living room of their apartment with her mother. They twirled and dipped, with exaggerated hand movements that made Kelly and her siblings laugh and clap. When the song ended, he would bow and her mom would curtsey. Even her brother, who was already a teenager and had begun to build a wall around himself, couldn’t help but smile. She pushed the seek-track button on the car’s CD player, jumped to the song and settled in for the five-hour trip. With only a brief stop or two, she could arrive around 11:00, when visiting hours started for the day and not lose too much time going through security. She needed some answers to settle her mind, and she hoped she could get them with her visit.

Urban congestion gave way to suburban sprawl and then came the vast emptiness of rural New York. Lush and green with rolling hills, farm silos and cows, it almost seemed like a different country. Even from the highway, through her open windows, Kelly could smell the sweet and earthy scent of hay and manure, the odor familiar to her from her years of living in Kentucky, before her dad left the military and her family moved to New York. Unlike Kentucky, as she got closer to Dannemora, the scent of fir and pine and spruce also permeated the air, a different kind of sweetness, that smelled like life and of permanence, rather than decay. In some spots, old trees towered over the Thruway, blocking out the sun, their trunks and needles throwing strange shadows on the road, ancient creatures guiding her passage north.

Six hours after she had started, Kelly sat at a table in the inmate visiting room of the Clinton Correctional Facility, a maximum-security, men’s prison in the Adirondacks, 400 miles from the Canadian border. Many lawyers she knew referred to the prison as Dannemora, the name of the town where it was located. The visiting room was busy, the sounds around her more like those of a primary school than a prison, but she knew that most families could rarely, if ever, make the trek. The distance and the cost of the trip made it a once a year endeavor even for families who could save for it. They skimped and sacrificed for the journey, which often required an overnight stay, especially if you traveled with children. Christmas time was tough because the weather made the prison impassable from New York City, the home of most of the men incarcerated there. The long, brutal weather inspired some inmates to call the prison Little Siberia. Old timers said that there were only two seasons at Clinton, winter and July.

Little Siberia held nearly three thousand men, making it the largest prison in New York State; it is also the third oldest. Lucky Luciano was a resident and so was a famous rapper, who served nine months last year on a rape conviction that he vociferously denied. Robert Chambers, the “preppy murderer,” who was convicted of killing Jennifer Levin during what he dubiously claimed was rough sex, also spent some of his nineteen-year sentence for that crime at Clinton. The facility was notable, too, because inmates throughout New York State wear uniforms manufactured by prisoners there.

The prison’s North Yard is famous among corrections buffs for its so-called Clinton Courts, patio-like areas where inmates can claim quasi-proprietary rights to small, scrappy patches of land, abutting a hill. Prisoners can outfit the spaces as they please, within Department of Correction rules. This characteristic is unique among corrections institutions in the United States. Many inmates plant flowers and vegetables on the patios during the area’s short growing season, and erect low, make-shift fences to mark their property lines. DOC rules prohibit installing any items that would obstruct the view from the guard towers that surround the yard. Corrections officers armed with long guns man the towers, which can be entered only from outside the walls of the prison, in case of a riot or an insurrection. In the event of an uprising, this practice prevents cons from gaining access to the weapons in the towers.

The man Kelly came to visit had his own Clinton Court. Other convicts had planted marigolds, daffodils and lilacs there for him, as well as rosemary, basil and mint. When spring days were bright and clear and warm, and the flowers bloomed orange and yellow and purple, he enjoyed sitting in his court, in a plastic lounge chair some do-gooder had donated to the prison, specifically for this purpose. The garden reminded him of one that his mother had tended and nurtured when he was a child, on a tiny plot of land behind his family’s apartment building.

That man, sitting across the table from Kelly, wore a dark green jumpsuit, with his inmate number stenciled above his left breast. The suit looked starched, with the wrinkles pressed out of it, and his sleeves were rolled up in matching two-inch cuffs, revealing arms knotted with muscle. He wore his hair in tight cornrows, his face was smooth and unlined and his body compact. The man sighed and pursed his lips. They had both grown weary of the small talk but the man voiced his impatience first.

“I know you ain’t come here for our trip down memory lane. Why are you really here?”

“What do you know about the drug trade around the Mitchel Houses?”

“You put some money in my commissary? The government tying up every dollar I have. Even in here, there are things you need. You ever try state issue toothpaste?”

“Please. I need to know.”

“What I hear, Dominican crew has that place locked down. They small-time players, though. No ambition. Happy with the slice of pie they got. Nobody moved on them. Yet. But rumor has it, some Jamaicans dudes are gonna test their defenses. The man in charge, Tino, let his guard down. Some people say he’s losin’ it and the spot is ripe for the taking.”

“You think they put Javan to work?”

“He’s black, right? No. Those boys too parochial. Mostly kin working for them. No brothers with that outfit. Black man need not apply. Strictly Dominican. You worried your man is clocking, or maybe a soldier?”

Kelly hesitated. “Not me…

“…Oh. It’s that white boy you working with. You know what I always say. Never underestimate the white man’s predilection for assuming the worst about black folks. That goes double for lawyers. What’s your gut say?”

“He didn’t do this. What are you hearing?”

“Everybody’s chattering in here, but nobody’s saying nothing. Tino, that benighted muthafucker who runs the spot is volatile but he ain’t that volatile. I doubt he’s connected. After the shooting, TNT brought fire and brimstone down on him. If he did order it, he made things worse for himself. He’s not moving any product now. His market collapsed, his market presence toxic. Seems random to me. Hard to see how anyone benefits from droppin’ the cop. A beat cop? C’mon.”

Alton clucked his tongue.

“This is the act of someone who’s aggressive and can’t control that aggression. Acting out with no purpose. ‘Cept maybe makin’ a rep.”

“Javan is way too passive.”

“Guys in here say your man is a simpleton. Collects garbage and sells it? How’s he gonna get it together to pull this off? And for what? Doesn’t take Sherlock Homes to figure out they busted the wrong guy.”

Alton thought for a moment. “Any witnesses you know of? That could be trouble.”

“We think it’s the cop’s word against our guy’s. The partner. No other witnesses.”

“Sound familiar, don’t it.”

“Alton, I just came to talk.”

“Why do you do what you do? After what happened to both of us? You grease the wheels is all. You’re a cog in their war machine. Make it easier for them. This shitstem will never be fair to people like you and me.”

“I’m doing my job. The system needs people like me.”

Alton’s demeanor softened and he smiled. “Even as a baby you thought you were born just to light up the room, that you were special. Pops couldn’t stop talking about your eyes. Always with that ‘African princess’ shit.”

“I must have been an annoying baby sister.”

“Me and Kim plotted ways to make you disappear. We wanted to tell Mom and Pops that somebody kidnapped you. Flip the script. Make it a childless, old white lady.”

Kelly smiled at the thought. Alton scrutinized his sister, the anger brewing in him again.

“Been up north how long since we last saw each other? Or even talked?”

“I’m working a lot. And it’s not easy to get here. You know I don’t have a car.”

“Didn’t get any visits at downstate either.”

Alton Matthews sat back in his chair and folded his arms across his chest. He softly shook his head, and looked around the room, his expression a rictus of bitterness. He shrugged his shoulders and stared at his sister.

“Alton, you said you wouldn’t do this.”

“You believed the worst about your own brother. And Pops? He wrote me off a long time ago.”

“He was sick over what happened…”

Alton Matthews met his sister’s gaze and locked his eyes on hers.

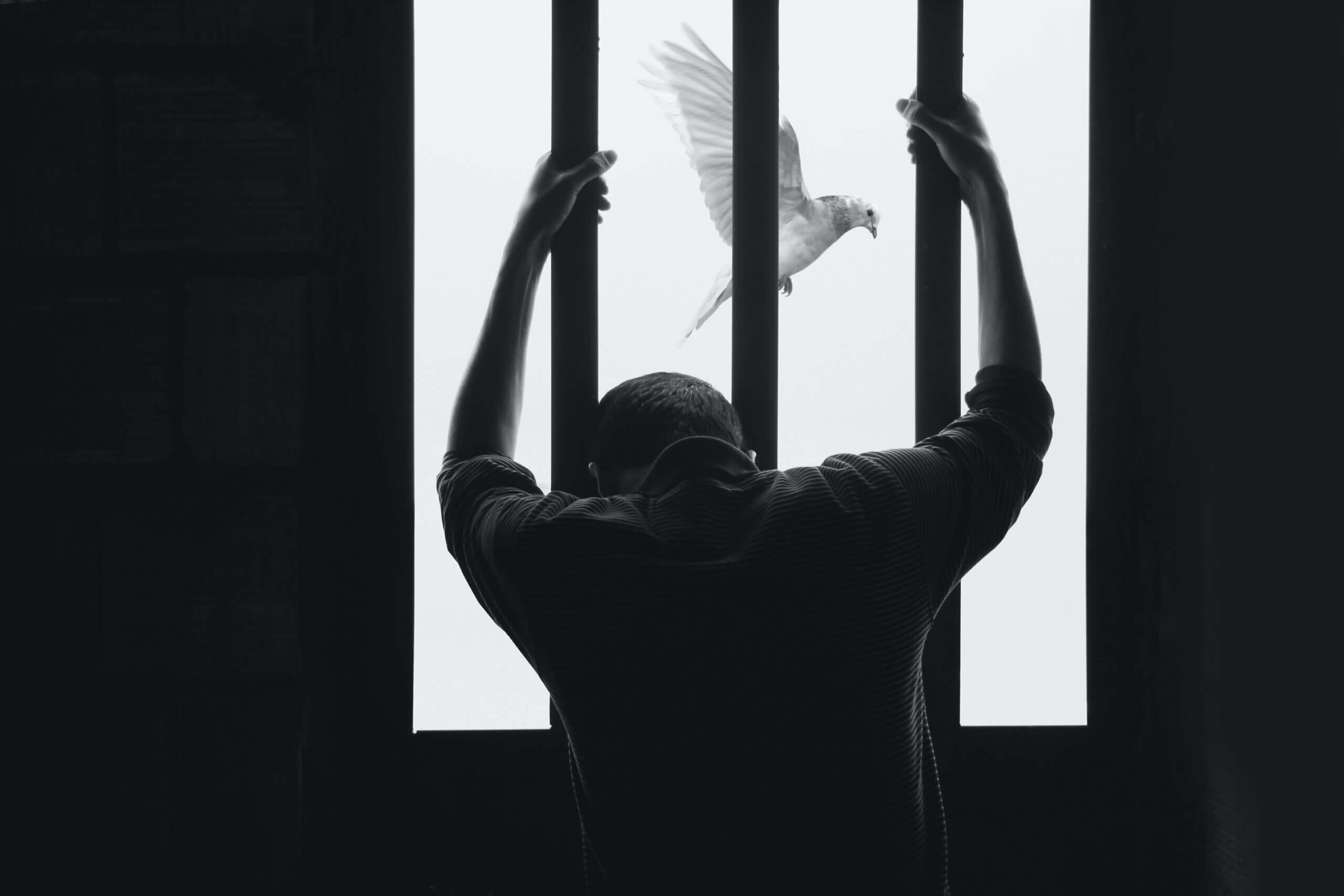

“Don’t believe everything you read in the papers, little sis. Like your man, a lotta guys up in here? They guilty of nothing more than growing up in the projects.”