Creative Nonfiction

Since assuming a second term of office on January 20, 2025, Donald Trump, with the assistance of his zealous lieutenants, has, among other “accomplishments,” pardoned every one of the 1,500 rioters who were charged with participating in the attack on the Capitol in 2021; forced universities to capitulate to ideological demands at the risk of losing their federal funding; deployed the National Guard to traditionally liberal cities, where it is neither needed nor wanted; gutted or largely dismantled USAID, the Department of Education, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and other essential governmental bodies; licensed the abduction by masked agents of immigrants, students, and others for perceived crimes against the state; created a meme coin in his likeness that is thought to have enriched him and his family by more than a billion dollars; and produced a charming video which shows him as a fighter pilot gleefully dumping excrement over the heads of Americans gathered in protest against his presidency.

And what have I accomplished in the same time span? Well, I published essays on literary and cultural topics in The Hedgehog Review, Plough Quarterly, The Write Launch, The Republic of Letters, and Pop Matters and won a small literary prize, while accumulating about thirty rejections in the process. Do I sense a slight discrepancy, not merely in volume, but in order of magnitude? Here I am, writing my reflective, gently ironic essays while a criminal psychopath and his goon squad burn the world to the ground. What’s a minor littérature to do?

My dilemma is the dilemma of slightly more than half the adult population of the United States. Whatever our vocations and avocations may be, merely going about our ordinary lives can’t help seeming incommensurate with the thorough-going assault on decency and democracy that constitute the essence of Trumpism. What are any of us to do?

Well, we can vote for Democrats, march in protest rallies, write letters to the editor, volunteer for election monitoring duty, mail off checks to ActBlue, Indivisible, and other opposition groups. What we shouldn’t do, in the face of the MAGA catastrophe, is question the validity of the vocations and avocations – not excluding the writing of essays for small literary magazines – that bring meaning and purpose to our lives. Never has the inessential seemed more important. The merely human will never topple the monstrous. Even as I write this, the Trump administration is shutting down pediatric brain cancer research. How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea, / Whose action is no stronger than a flower? Well, it can’t. What beauty – you could call it curiosity or kindness or generosity, if you prefer – can do is assert its right to existence. Trumpism can kill – has already killed – a great many things. It can’t kill that.

I'm not especially political, and I’ve always envied those friends of mine who read Antonio Gramsci for fun or relish diving into a microscopic analysis of a disastrous Supreme Court ruling. What for them is a passion is for me a citizenly duty. Although I wouldn’t want to deprive myself of the intelligence and acuity I find in the political journalism of Anne Applebaum or Sean Wilentz or Mark Lilla, for example, I generally turn to the literary and cultural pages first. I'm Blanche DuBois with a social conscience – I want my political analysis served up with a dollop of Art and Beauty. Contrary to the dogma asserted by my fellow progressives, I have never believed that the personal is always and everywhere the political, and I proudly assert my right to redemptive frivolity.

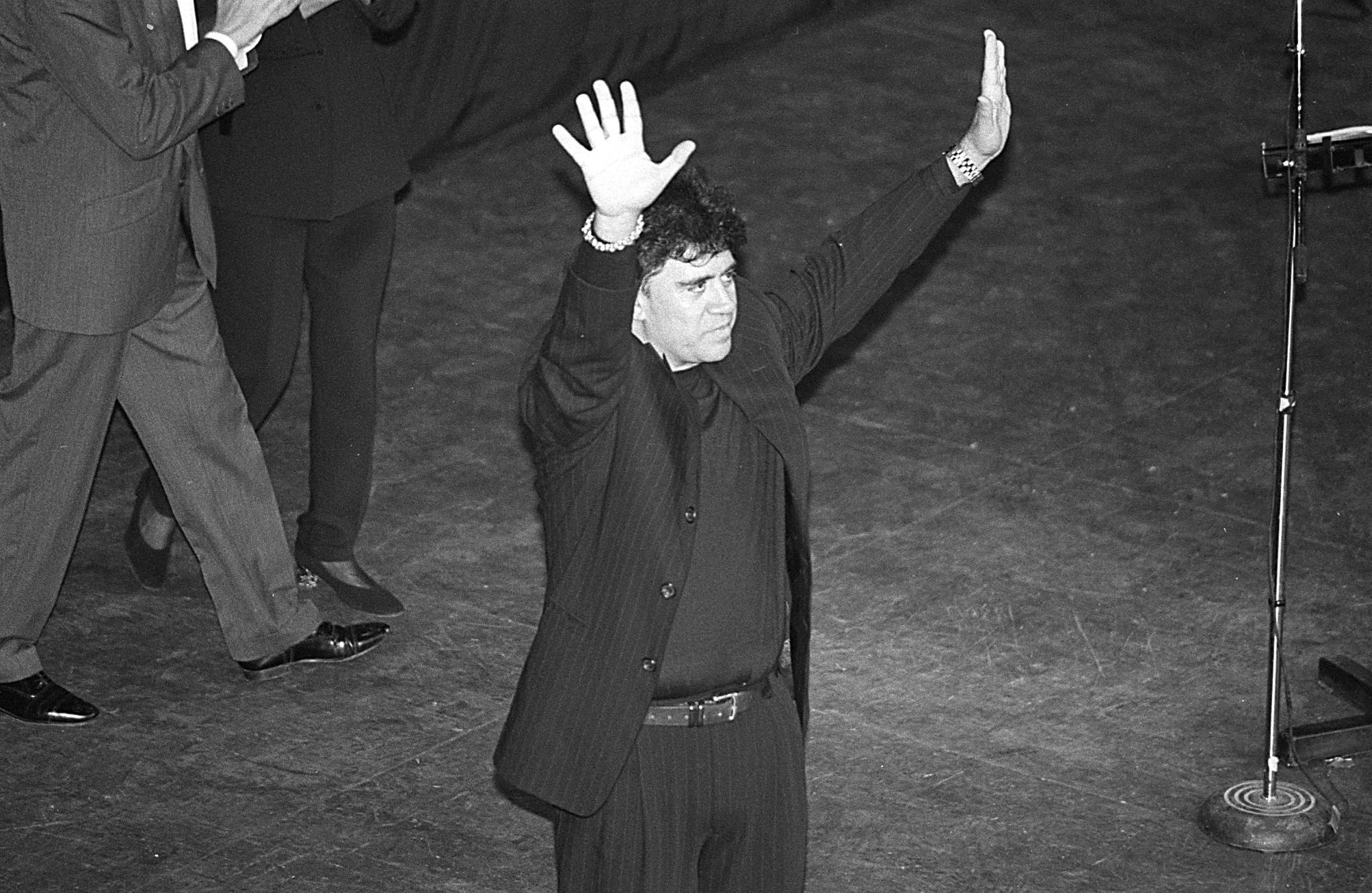

My guide to the apolitical, the patently irresponsible, the deliriously giddy, is Pedro Almodóvar. He’s also my guide to the socially informed, the historically aware, the judiciously partisan. When he came to fame in the mid-eighties with a series of outrageous, gaudy, gender-bending farces, Spain was still emerging from decades of spiritual torpor imposed by the National Catholic dictatorship of Francisco Franco. Those movies were conceived as if in fulfillment of a credo that Almodóvar stated as follows: “My rebellion is to deny Franco. . . I refuse even his memory. I start everything I write with the idea, What if Franco had never existed?” And in a way, Almodóvar won and Franco lost – if we can overlook, for the moment, the pile of bodies left by four decades of Francoist repression. It wasn’t the Generalissimo who restored Spain’s reputation in the world; it was, at least in part, Almodóvar and the punk rockers and comic book artists and cabaret performers who formed the nucleus of “La Movida,” an explosion of bohemian energy starting in Madrid and radiating outward to other Spanish cities. When Almodóvar’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (about as perfect a farce as has ever been put on film) burst upon the world in 1988, Spain suddenly looked open and vibrant and sexy again.

It would be hard to argue that the lesbian junkie Mother Superior who presides over her equally debauched vestals in Dark Habits (1984) represents a serious or searching critique of institutional corruption. A nun casually tying up and shooting smack in the presence of her (female) lover is, above all else, a good joke – if you find that sort of thing amusing. (I do.) But if the personal isn’t necessarily the political, it isn’t necessarily apolitical either. From the first, Almodóvar sought to avenge himself on Francoism in the form of a camp sensibility that affirmed hedonism, recreational drug use, polymorphous sexuality, and other non-normative practices that could get you killed or locked up in Franco’s Spain. Luckily for us moviegoers, he had the wit not to frame his agenda in those portentous terms.

As his career progressed, Almodóvar gradually turned from the camp exuberance of his early movies to a more sober consideration of certain intractable social and political realities – without, however, surrendering his fondness for the despised and disreputable conventions of Hollywood melodrama. For me, that progression found its maximal expression in Parallel Mothers (2021), a movie that brought together the plotty convolutions of a 1950s “woman’s picture” (Penelope Cruz as a single mother with a terrible secret to hide), with a counternarrative concerning the inescapable burdens of the Spanish Civil War reaching into the present. No gritty black-and- white cinéma vérité for Almodóvar. Few movies have ever looked so color coordinated, and Penelope Cruz brings an unabashed movie-star glamour to every scene. These two apparently contrasting elements – the cinematic artifice, the historical realism – come together in a scene in which Cruz (romantically involved with a forensic anthropologist working to discover the unmarked graves of citizens assassinated by Franco’s Falangists during the Civil War), loses all patience with an infatuated and willfully apolitical younger woman who believes in “looking to the future” and thinks that any such investigation into the Spanish cataclysm merely “opens new wounds.”

“It’s time you know what country you’re living in,” Cruz tells her in exasperation, and says that until the bodies of the grandparents and great grandparents are found, disinterred, and given a decent burial, “the war won’t have ended.” And then Almodóvar, the former orchestrator of riotous camp excess, ends the movie with an image of ordinary people from the present day lying in the graves in exactly the positions of the skeletons that had just been excavated by the team of forensic anthropologists.

Then the lights came up. I could barely stand.

“It’s time you know what country you’re living in” is an admonition that applies to us all. Until Donald Trump was elected – twice (though losing the popular vote by almost three million in 2016) – I thought I had no illusions about the imperfections of American political life. Look how wrong you can be. As I struggle to reconcile myself to unimagined political realities, I find myself deriving lasting sustenance from the uselessness of the art and music and literature I have always loved. With American democracy threatened as at no time since the Civil War, is this the time to hash out with a friend the five greatest R.E.M. songs? Yes, more than ever. First of all, “Shiny Happy People” is a masterpiece masquerading as a bauble, but more to the point, I refuse to allow the moral degenerate in the White House to colonize my consciousness. He has already taken up far too much space in the national psyche. Really, Trump is too stupid (a “fucking moron,” as his first Secretary of State called him) to have any coherent political ideas. All he wants is your exclusive, undeviating, enrapt attention. Don’t give it to him.

How much bad news can you take anyway? I balance my citizenly responsibilities with a due regard for my mental health. I vote, I march, I donate, I stay informed, but I carefully ration my consumption of political news, and I'm certainly not going to listen to the most odious sycophants in Trump’s cabinet suck up to their fickle and insecure patron. I had a friend who used to get up in the middle of the night to catch up on the day’s outrages as reported on CNN and MSNBC – and this was during the far less extreme first Trump administration. Not only could she rarely get back to sleep, but it seemed to me that she had conceded victory to the Trumpists, whose dearest goal has always been to “own the libs.” One of the things I’ve come to appreciate about living in New York City for decades, is that the multi-cultural, multi-racial, nonbinary, lavishly tattooed and pierced hipsters, who can be (let’s face it) rather annoying in their righteousness, will not be “owned” by anyone. Although the MAGA faithful may decry New York as a Gomorrah of woke socialism, no amount of bullying and intimidation from the White House will stop its citizens from attending off-Broadway plays in which the principal performer and playwright drugs herself into unconsciousness and, as a symbolic protest against male sexual violence, allows cast members to violate her body. Personally, I’d rather go to a Knicks game, but you can’t say the performers and the audience lack the courage of their convictions.

Although it is, thank goodness, a stretch to invoke the French Resistance, that distant historical parallel might be worth considering. It wasn’t the Maquis that drove the Germans out of France; it was the big guns of the Allied armies. The important thing about the Resistance, however, was that it existed. Try as they might, the Nazis couldn’t extinguish that feeble, flickering light. Similarly, no coteries of avant-garde artists and their camp followers are going to vanquish Trumpism. That will happen only when Democrats start winning more elections and the Republican Party renounces authoritarianism and the cult of personality. How these goals are to be achieved is more than I can say. Resistance takes many forms, and while I would prefer the practical political form that defeats Trumpism and all the cruelty and recklessness it stands for, I’ll gladly take the less practical form of avant-garde protest so long as that protest signals a refusal to be cowed. Fortunately, I'm not required to sit through excruciatingly “transgressive” performance pieces in converted warehouses. I have the example of Pedro Almodóvar, whose movies offer a model of resistance that encompasses pretty much everything worth fighting for: the gloriously silly, the flamboyantly melodramatic, the irreducibly human, and, when push comes to shove, the fiercely committed.