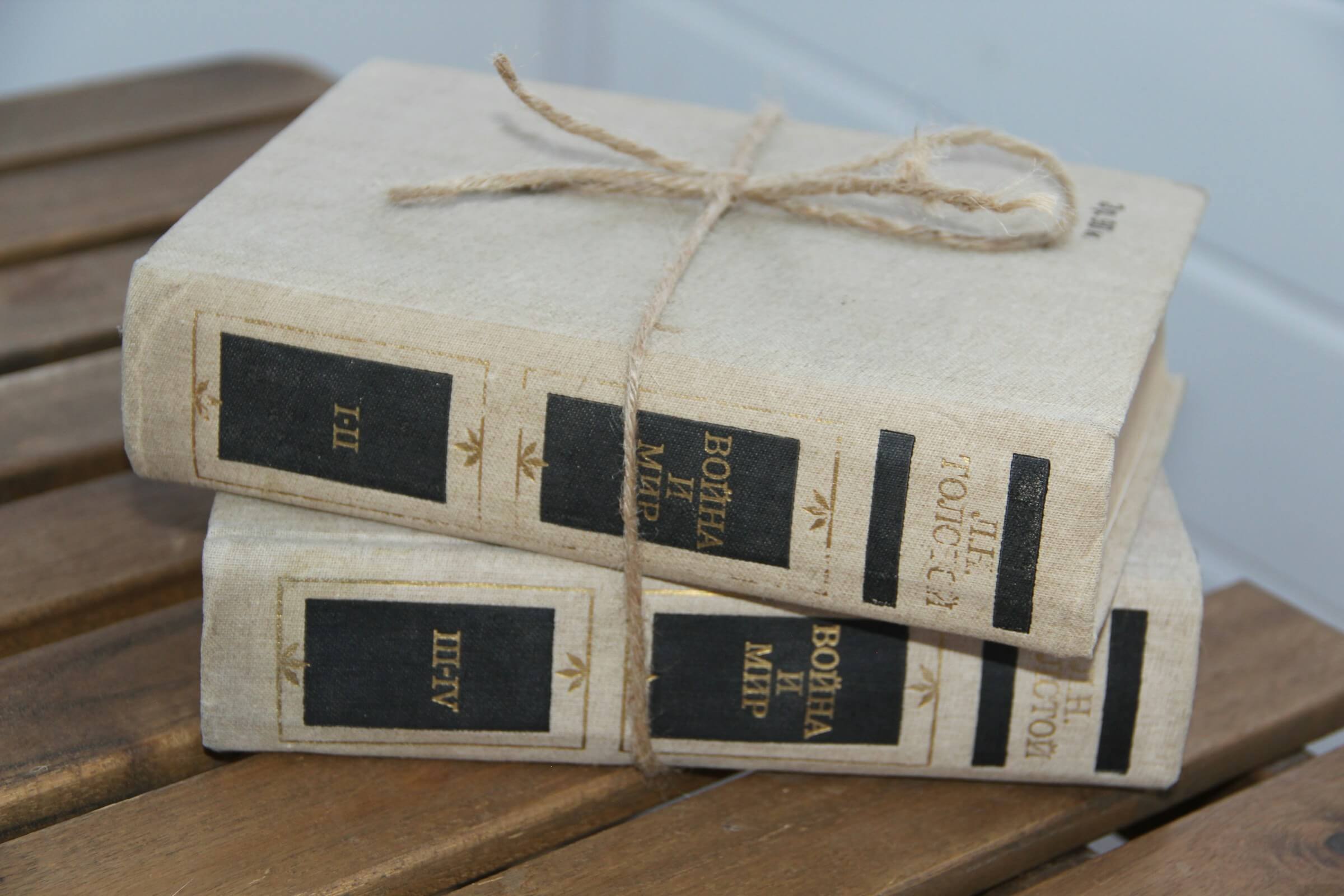

Good-Bye Leo Tolstoy

I am finally admitting

that I am never going to read War and Peace.

I started a number of times,

printed out a cheat sheet with the cast of characters,

made many a tasty snack,

read to around page 100,

and each time abandoned the project.

My momentous decision to kiss Leo good-bye

was made last week

when I organized my office,

saw that the pages of the paperback were yellowed

and the thick spine broken from using the book

on windy spring days as a doorstop,

not to mention the chocolate stains

smeared over the Norton notes.

I cleaned the book up the best I could

and placed it carefully in a donation box

for a sale at the local library.

Surely someone else will be thrilled to own it.

However, I feel abandoning this masterpiece

is a failure of character on my part,

though I did read Anna Karenina start to finish,

cried at the end when she gave herself to the train.

I also read the interesting parts of a Tolstoy biography.

How he gave up most of his copyrights to live as a peasant,

altruistic fellow that he was.

Pissed his wife off because of their 13 children

and who can blame her?

But none of that is relevant

or a good defense for my literary turpitude.

I’ve moved on to staring down Ulysses.

The Language of Trees

My son tells me

more trees are falling

because of global warming.

I feel sad

and it strikes me how magnificent

my favorite oak is.

How it shades the driveway,

the trunk rugged, broad and tall,

a network of roots

like tributaries

rippling in all directions,

the crown of leaves

a thousand tongues,

the strong limbs a portrait of its foreign grace.

A few months after,

the summer wind whirls

and plucks the tree out of the ground

as if it were a daisy,

drops it on my house,

on timbers,

measured, sawed, framed,

and nailed together

by the carpenters among us.

With its last breath,

the tree makes a final statement.

If only we had ears to hear

the language of our trees.

I Detect Lord Byron

Gneiss, a common rock in Connecticut.

Some are gray with white stripes

stacked up the sides like a layer cake.

I find a small one with distinct rings

to edge my garden,

but I keep looking for a showstopper.

The oldest gneiss, found

in the Minnesota River Valley,

dates back 3.6 billion years.

I think about how old the stone

in my pocket might be

as I walk slowly through the woods

carrying history,

eyes peeled.

A friend I hike with tells me

we breathe the same molecules

as dinosaurs and Abraham Lincoln.

I inhale deeply and imagine

I detect Lord Byron.

A miniscule bubble

could have drifted over the ocean

and floated into my woods

like a speck of Don Juan still in wanderlust.

I stumble upon the prize rock

to the side of the trail along the river.

Smooth in my palm

from years in the water,

it has a band around the edge

and a white circle on its face

like an antique clock.