That old-time feel of can in hand loosens tongues as much as the contents do—our first beer and really our first chance to kick back since the two-day drive from Kabul last month. This is September 1971, Farah province on the border with Iran. Keynote honors go to the eldest: your humble servant. Sitting on the landing outside Werner’s room, I begin by saying Afghanistan was a big mistake.

“Mistake?” Werner pauses the Heinekens at goatee level, his grin in neutral. He’s German, like the UN honcho who brought the beers. The latter left this morning with driver and two assistants. He seemed pleased, relieved. We’ve launched a pilot program, food for work in the midst of a multiyear drought. Keen hopes ride on it—for the hungry peasants, obviously; the masterminds, professionally; the King, politically, local players, guardedly; and us, personally. Besides Werner and me, our team consists of two American volunteers and three Afghan engineers. The observant engineers are on the roof with Al, Peace Corps supervisor for western Afghanistan.

Eight cans total—our benefactors might have emptied a few on the way—equals two each for us in our first and only nonbelievers happy hour. We sip slowly to extend the duration. Irony if not humor alleviate the mid-mission slump reflected in posture and eyes. And it reverberates in my voice as I allow a hint of emotion. “Okay, Afghanistan wasn’t the mistake. It made up for one.” Or more.

* * *

A year ago spring, the Peace Corps offered Tunisia. The info packet portrayed a southern California without the smog. I’d escaped to northern California, I tell my beer buddies, both poles so different from the places I’d been.

As is Farah, which lacks electricity, running water, and women you can talk to. In area and entropy, the provincial capital where we live compares to my hometown in Pennsylvania with its family lumberyard that shut down this summer, a railroad track that last supported a train in the Fifties, and a movie theater that hasn't opened since the Twenties. Here, young men leave for Iran. There, homies asked about California. Employment wasn’t the draw. Let-it-all-hang-out was.

“You have a degree,” my father said. “Use it.” He meant get a job or go. Hello, San Francisco. I arrived late for the party, summer of ’69. The city quickly ate away at my savings and intention to postpone office routines as long as my body could handle the load. Imagining myself outside the box, I applied for a job as a reporter in Vietnam. Given the war’s unpopularity, I figured any application would be snapped up. I should have known journalists were drawn to disaster like flies to teahouses. Career was not a motivator, I told the editors. Nor glory. Like an auditor, I’d lay out the facts and let the reader decide. Perceptions evolved, including my own. Facts changed. Few Americans understood how complex the whole thing was—Afghanistan if it were organized, with more people, money, partisans, and foreigners. Shrimp with your rice. Chopsticks. Vegetables. Beer. Coffee! Oh yes, rain. Violence. Can’t forget that. You need experience, the editors said; start small. No thank you, I came from small.

The Peace Corps wasn’t so particular. That should have raised a red flag. By then I’d hired on with an accounting firm. Do-the-math paid the bills. It also allayed parental concerns.

I gave my firm two weeks’ notice. “That was the question with you,” the personnel director said: “Will he stay?”

I called my parents. A sniffle came over the wires; spring fever meant hay fever to my mother. “Tunisia,” I repeated. They’d never been overseas. “On the Mediterranean.” A sigh. “Good for the sinuses. Mom?” She was the talkative one. My father cleared his throat. “Dad?”

The practical one. My mother’s sisters saw a lot of him in me. We went to the same barber until I left for college—flattops, his without the Butch wax. Glasses, check; lean as a bean, check; both good with numbers. “Doing what?” he said finally.

“Teaching English.” As a foreign language.

“College?” It sounded like he was speaking through a handkerchief.

“High school.”

Was that a snort? Those who can’t do, teach, he liked to say. “How’s the pay?” He should have been the accountant. “And for how long?”

“Two years.” You could always quit early.

“What about after?”

I cleared my throat. That also ran in the family.

“Wasn’t Vietnam enough?” As the Arctic had been for him in The Big One.

Maybe if I’d been a journalist.

“Tunisia!” my mother exclaimed. It took a while to sink in.

“South of France,” I said. “You can visit!”

Next day, the Peace Corps called to say Tunisia had fallen through. We’ll get you something, they promised. Two weeks max.

* * *

Day before deadline, my grandparents flew in for a long-scheduled visit. Forty-eight years earlier, the biggest adventure of their lives, they left their only child, my toddling father, with Grandpa’s sister and brother to join a couple driving to San Francisco. When I asked at the baggage carousel what they remembered about the city, their heads wagged fondly. “Ooh.” Grandma flicked her wrist. “All that water.” She laughed. “Hills.” They’d had no occasion to go back. “Flowers.” I didn’t expect that. Her hands fluttered. “Palm trees! Fog. Foghorns. Ooh, it was chilly.” She looked up, the sun between clouds. “Like now.”

“Rough road,” Grandpa said. “Motorcar got stuck in the mud.”

We piled into my vintage roadster, an off-black Triumph, its trunk secured with twine to accommodate the luggage. “You shouldn’t take off work for us,” Grandma protested as she scooched into the jump seat. “We could have gotten a taxi.”

Unemployed as of that morning, I was free to show them around. My father saw his father six days a week at the lumberyard. “Didn’t Dad tell you?”

No. Their first trip out of state in nearly fifty years, their first grandchild reveals he’s fallen—make that jumped—off the career ladder. Again. If a kid did the Peace Corps at all, he did it right out of college instead of the Army. They were detecting a pattern.

“Where will you go?” It’s what everybody asked. The Peace Corps kept sending materials about sun-drenched, postcolonial, multicultural Tunisia.

“I’ll find out tomorrow.” The world was my oyster.

The next day I stayed in, phone at the ready, and let my grandparents recover from jet lag, breakfast and lunch on their own. For dinner we’d do Chinese, a first for them. After checking the mail—no news being bad news—I dialed up Washington, DC.

You need to talk to Mr. So and So, the receptionist told me.

“He’s in a meeting,” his secretary said. “He’ll call the minute he gets out.”

It must have slipped his mind.

The following day we planned to take the cable car from my grandparents’ hotel to dinner at Fisherman’s Wharf—after I spoke to Washington.

Five minutes before East Coast quitting time, I called.

“Oh dear,” the secretary said. “He’s on another line.”

“I’ll hold. And by the way, I called collect.”

Mr. So and So came on fast, like he talked. He had the perfect job for me—budgetary advisor in Malaysia. Ministry of Finance.

The Peace Corps conjured up villages, not finance ministries. I told him I was looking for a new direction. I wrote that on my application.

“Summer cycle about filled.”

Could he promise something if I waited till fall?

“We’ll start over.” Already he was tired of me. “No guarantees.”

“Don’t you have anything?” I lived in a boarding house. My room was ten by twelve, closet the size of a phone booth, bathroom across the hall. “Besides Kuala Lumpur.”

“We’re down to Iran and Afghanistan.”

On the map and probably other ways, Iran was between Afghanistan and the West. “Afghanistan,” I blurted. It had a ring.

Tunisia represented a course correction. Afghanistan, a step beyond.

* * *

My grandparents were the first to know, at dinner after we tasted a chardonnay recommended by our waiter. They swirled it around their glasses, wishing, they later admitted, for whiskey sours. Grandpa studied the menu in a manner that made me realize he, like everyone, had feelings as well as stories to share or, in his case, not. He spoke Pennsylvania Dutch as a kid. Football got him into college and off the farm. I know because Grandma told me. She met him at the town bakery across the street from her house.

“Caravans!” She recalled James Michener’s novel, a bestseller when I was in college, although she hadn’t read it. None of us had. “Oh, Frank. That’s exciting!”

“Between Russia and India, right?” Grandpa put the menu down. “Stuck in the past.”

Grandma laid her hand on my sleeve. “That’s why they have the Peace Corps.” The lumberyard had been her father’s.

The waiter suggested abalone. Freshly caught, it paired well with the chardonnay. Grandma and Grandpa had never tried either. Grandpa’s treat. He had helped with college costs, and in my senior year he’d offered to do it for grad school, business or law degree, something with a future, anything but the Army.

Farah is the bottom of the barrel to our young engineers, a place for paying dues. For us foreigners, it’s an adventure, summer camp with a purpose. “Look at us,” I say. Cold water discourages shaving. It comes out of a bucket we hoist from our well with a windlass. A larger bucket handles laundry. Once a week we visit the public bathhouse. “Would this make anybody’s grandparents happy?”

“Go out in the town.” Perseverance hardens Werner’s smile. “We making anybody happy?”

“Ourselves?” Paul’s written a book about Thailand’s snakes, focus on king cobras. We heard the short version on a long drive to a dry oasis. Charlie hates his home state of Mississippi but isn’t ready to discuss it. That makes him a good listener.

“The farmers?” Werner once was a carpenter, and he behaves like one. Measure twice, cut once. His goatee says think again. “That’s the question.”

“Hopeful?” We’ve seen signs.

Werner strokes that goatee, brown and bristly in keeping with an ursine build. “Will it last?”

Paul and Charlie watch, like a jury, for my response.

“Every day a new day.” Tra-la-la. What else can I say?

Here’s what I leave out. Aerograms to an increasingly enigmatic girlfriend carry disembodied phrases looking for a home. The time lag drives me and, I think her, around the bend. I reply to her last letter after she’s written another, one I have yet to receive, that’s in response to my previous aerogram. Or is it two back? That morning I crumpled up a draft.

It seems, she last wrote, you’ll start over. I heard her voice curve into a question it hurt to ask, to answer. I pictured her eyes, the intensity. We saw the world the same. But we came at it from different places, speeds, and routes. We didn’t connect until after my grandparents left. In our brief time together, she and I assumed Afghanistan would exhaust the wanderlust. We now appreciate how little we knew ourselves or each other.

My too-pooped-to-party bros nurse their beers as I reach for a second. Most of this is new to them. They’re either stunned, bored, or patiently waiting their turns. A swig allows me to pick up where I left off.

* * *

On the spur of the moment, she joined me for the drive from San Francisco to the Peace Corps staging center in Philadelphia. Although the roads weren’t rough anymore, at least my grandparents knew their destination. They returned by train.

She and I accomplished it in the Triumph. The headlights didn’t work, so we couldn’t drive much past sunset. Rain, when it fell, squiggled between the windshield and dashboard, and the top wouldn’t stay up above twenty miles an hour. That’s what made it fun.

The country we drove through wasn’t much fun. The toll collectors, truck drivers, mechanics, servers, fellow diners, and motel clerks we met seemed down in the mouth. The Sixties were over. Nixon had his hands on the reins, and nothing changed. San Franciscans saw Middle America as foreboding—there be dragons—and the estrangement was mutual. San Francisco was too sweet, the heartland too sour. I wanted both, like in that Chinese restaurant.

For a few days we had it—the thrill of quasi-elopement, the agony of impending separation. Pushing the Triumph to its limits, we felt like Bonnie and Clyde without the crime or soundtrack. The radio shorted, and we filled the airwaves with our voices, so much—even the silences—to ponder.

Do you really have to do this? was the question she never asked. I wasn’t her first, she wasn’t mine. She’d be better off if I went. “Get it out of your system” was as much as she said.

The Peace Corps, I told her, could get me in step with my generation.

“What?” Such musicality in that! She could look astonished, peeved, and jaded at the same time.

It was hard to explain. “Different drummers.”

She waited me out. Wyoming ahead.

“They made other choices.” My generation made the music. They made the movies.

“Or no choices,” she said.

“Exactly.”

“Like me.”

“You.” I downshifted for a curve. The engine puttered. It purred. “Everybody.”

“You mean Vietnam? I don’t care. Your friends don’t care. We care about now.”

Motivations were many: do right, for example, do it well, and do it far from home. I shifted into high. “What are you going to do?”

We’d gone over that. She wrung her hands, straightened her arms, hair in red-ribboned pigtails to withstand the wind. Like me, she’d worked in an office, had her degree. She wanted a family, she’d said in Nevada. Who didn’t? Timing was everything.

She spoke softly, leaning in so I could hear. “You sound lonely.”

Okay, so Afghanistan was also a mistake.

Our trip happened soon after the Cambodia incursion and the bloodshed at Kent State and Jackson State. Vietnam split our nation apart. Culturally, I had grown close to the longhairs. Peace, love, let the good times roll—what wasn’t to like? Viscerally, I felt bound to brothers still in arms. Only the love-it-or-leave-it crowd left me cold. They formed the new majority, and they hadn’t earned it.

I took her to her parents’ house on a Sunday morning in Ohio. With her mother and father on the front stoop stiff and frowning as though we were way past curfew, we never had a proper goodbye. Flittery fingers, quick kiss, try again, once more, tear-washed eyes, an embrace to remember, a suitcase to deposit. A handshake and the briefest of introductions. Words failed. None of us knew how to get past the shock. My own parents lived in Philly’s outer suburbs, and I needed to be there before dark. The staging center expected us recruits the following day. Processing would take the better part of a week, with Friday reserved for personal business. Fly Saturday.

On that bumpety Pennsylvania turnpike I felt as empty as the passenger seat. Mixed with loss was fear the Peace Corps would be populated by ignorant, arrogant do-gooders. The Army lived up—and down—to its reputation. The Peace Corps surprised. True believers departed early, ceding the field to us improvisers who remained.

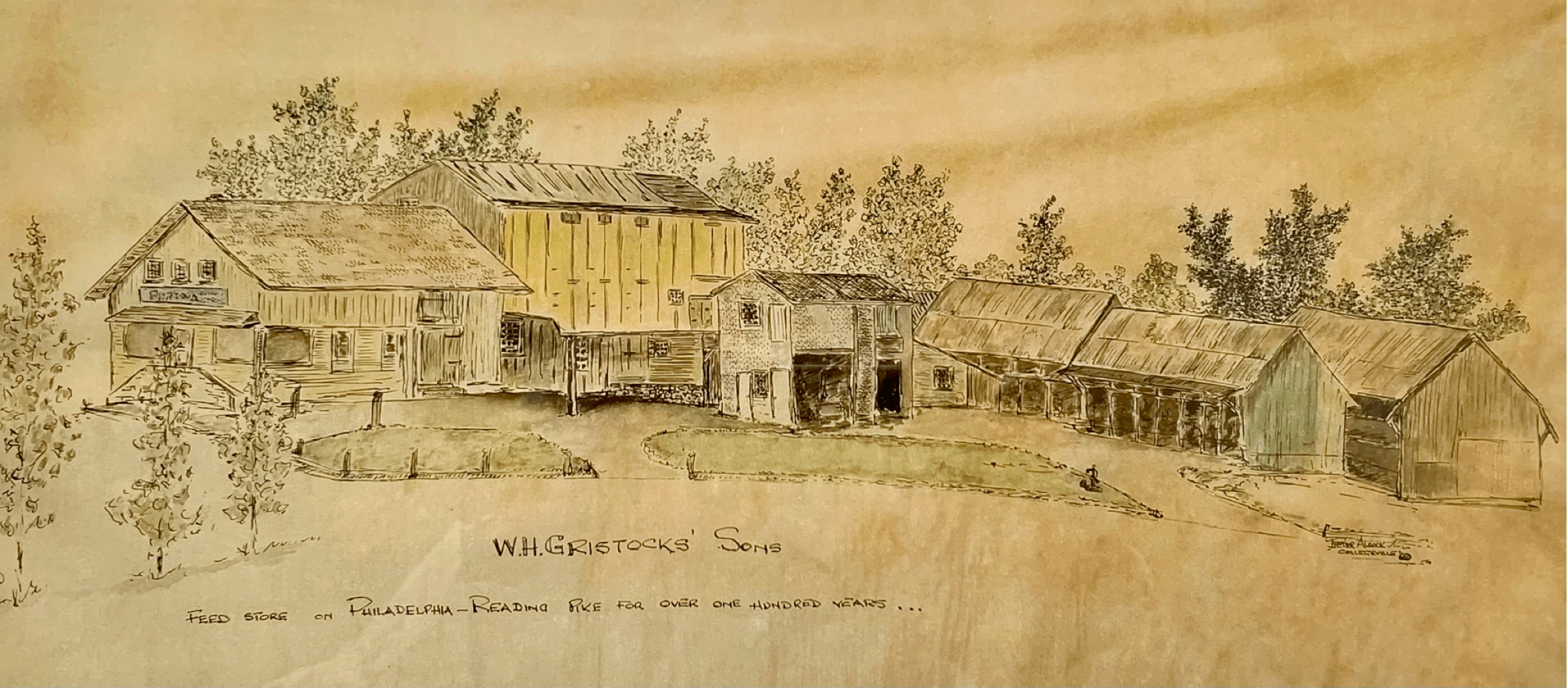

Driving in from Philadelphia, the first thing you noticed after the Bridge Hotel, where my grandfather said George Washington once dined and he now took his midday meals, was W. H. Gristocks & Sons, coal, feed, and lumber since 1865. Grandpa kept the books in a side office with desk and chair. Lacking such amenities, Dad stood in the showroom behind a high table with a phone, notepad, receipts book, cash drawer, and hand-cranked adding machine. Each day Mom made him the same lunch, which he tired of but accepted as his lot: Lebanon bologna with French’s mustard on Wonder Bread, Ritz crackers as accompaniment. Apple. He ate where he stood. They didn’t close for lunch. No sink or bathroom. You went behind the sheds.

Last winter, Dad wrote to gauge my interest in taking over the store. Grandpa was getting on in years, and they had an offer for the land. We always understood without speaking of it the question would arise, eventually. I just didn’t expect it so soon from so far away and to feel it like a punch in the gut.

Dad and Grandpa didn’t know how they’d manage if—when—the blue laws ended, and the chain stores moved in. “It’s a good deal,” Dad claims his father told him when he started. “You get Sundays off and a half day on Saturday.” Because Grandpa could no longer run it by himself, Dad hadn’t taken a vacation in eight years. Each evening he’d carry out a pouch with the day’s proceeds and stash it under the placemats in the dining room hutch. He’d deposit it at the bank on his way to work in the morning.

On discharge from the service, 1945, he thought about reclaiming his position as a government economist. He made a joke of it: after the war, he concluded, Washington would downsize. Also, Gristock was his middle name. And I’m a Junior. The day my draft notice arrived he told me I was making more than he ever did. I was a beginning auditor in Philadelphia, one week from graduation, and he hoped I’d do the smart thing, the safe thing, with the Reserves or the Guard.

Sell, I wrote back.

He’d seen the signs. He wanted to make sure.

The new owners tore everything down. An off-brand gas station will take its place. Grandpa retired to his rose garden, and Dad landed a position at an insurance company, with mates, bathroom privileges, pension, health insurance, sick leave, and accrued vacation. Neither has much regard for the Peace Corps because they associate it with Kennedy. They have the same problem with Vietnam. They’re old-fashioned conservatives who oppose foreign entanglements. They didn’t visit me there, of course, and they won’t here. They can’t afford the airfare, and my parents have to look after my kid brother. Our sister has already given them two grandsons. It wouldn’t do to see their eldest barefoot in native dress, not a chair to sit on.

My first year I taught English in a village the other end of the country. A start. This food emergency got me into the field. Our actions, our steadfastness, have shaken the status quo. Sky’s the limit, sand’s the floor.

Until leaving San Francisco, I usually just joked about my past. But the captive audiences associated with travel demand more. With accession comes vulnerability. Talking sets the process in motion. Listening lends balance. Writing gives direction. Our bonds went beyond words. Now that’s all we had. If there’s time tonight, I’ll try my hand at another aerogram.

Up on the roof, the engineers enjoy a hearty laugh. Al keeps them in stitches, forgetting for a moment the corruption that swirls outside like dust before a storm. Here at the landing, our backs to the wall, stars above, it’s Werner’s turn.

Another world.