At 6:10 on a March afternoon in Montgomery, Alabama, Ginnie Lackland sat on the steps of Miss Lily’s acrobatics studio, watching her classmates get picked up by their mothers. Ginnie was a big girl, almost seven, who could do front splits and a perfect backbend and was learning to flip herself completely around without touching the floor—what flying must feel like, she imagined. Miss Lily told her to think of a perfect circle.

Alice’s mother was the last to arrive; she had wavy blond hair and bright eyes that gazed down at Ginnie.

“Do you need a ride home, sweetie?”

“Nome,” said Ginnie, squinting against the receding sun. She closed her eyes and pictured circles; when she opened them, Alice’s mother was still gazing at her.

“Maybe we could give you a lift? Where do you live?” Three lines creased her pretty forehead. The street was quiet, the air shifting into coolness as the sun lowered itself into a stand of tall pines across the street.

“The base,” Ginnie said. “We live at the airbase.”

“Oh,” Alice’s mother looked confused. “Well, we can’t even get in there.” She pushed a strand of hair from her face. Ginnie thought of a small, good lie.

“Yessum. Well, Mama had errands to run. She’ll be here any minute.” She turned a smooth face up, at which the little forehead lines sharpened again. A minute more and Alice and her mother had disappeared.

Miss Lily’s studio was just a regular house in a regular neighborhood. It looked like anybody else’s; only if you went inside did you see that the downstairs was one big room with mirrors and barres and thick, blue mats. Miss Lily lived upstairs, alone. She was a widow. Ginnie imagined that upstairs, too, mirrors maybe covering every wall and even the ceiling. Maybe before she went to sleep, Miss Lily would stare up at her sturdy little self in the mirror as she performed perfect front flips and think about her star pupil, Ginnie Lackland—who, as it happened, liked to picture what people did when they were alone, as she herself almost never had the chance to be, what with her sisters and her parents.

But now she did, because her mother was late. She sat on the steps and thought about the lie she’d just told, what Gramma Lackland called a white one. What was a black one, she wondered. Ginnie’s mother had a secret right now that had to do with black and white. She imagined what her Grandmother Sparks would think of that secret, back in Red Hill, South Carolina. A different world, Ginnie had heard her mother say: We grew up in a different world.

On the street only a few cars passed now—it was a weeknight, fathers already home from work, mothers putting dinner on tables, children studying. Lights glowed on, house by house. Behind her, Miss Lily’s stayed dark. Her teacher was a private person, Ginnie had heard her mother say; she had no family, was maybe a foreigner. Even though Ginnie wasn’t foreign, she felt a connection. Sandwiched between her baby sister Hannah and that know-it-all Kari, she felt alone most of the time. And where was she from? Not from this neighborhood anymore, not from the base, not from Red Hill. Maybe her mother and father weren’t even her real parents. She could be an abandoned child, maybe even a foreigner.

The happy idea of kinship with her teacher propelled her from the steps. The stony chill had penetrated her thin pink tights and black leotard; she turned two double somersaults and kicked her legs—one, two, one two—high over her head to warm up, then pulled on a pink sweater from her bag. The streetlamps lit the sidewalks; on her teacher’s mailbox Ginnie saw the address: 1341 Lee Street. Last year, before they moved to the base, she and her family had lived four blocks over from here: 475 Commodore Circle. She would never, she thought, forget it, since she’d spent the happiest days of her life on that regular street, with her best friend Beth next door and the Millers’ collie across the road and on summer nights they had played Red Rover and Blindman’s Bluff every night until fathers and mothers called them in. On warm weekends, people had cookouts and parents sat in lawn chairs late into the evenings, sipping drinks and slapping mosquitoes while the children called Olly olly, in come free from the fringes of moonlit lawns. Ginnie had started her acrobatics lessons back then; that’s why her mother still brought her to Miss Lily’s on Wednesdays—for continuity, she said, even though, as she would sometimes add, it was kind of inconvenient.

Ginnie knew she could knock on her teacher’s door and call her mother, but the thought of walking to her old neighborhood by herself made her heart feel light; she might do cartwheels the whole way. Her friend Beth’s mother could take her home. She imagined her family’s surprise when she walked through the door. Ginnie’s my independent one, her mother would always say, but not necessarily like she was happy about it.

Right or left? She still had trouble figuring out which was which. She turned towards a lightness of sky and walked one block, then two. And wasn’t this the street where that little girl had drowned last summer, right in her own backyard, because her mother had left her in the pool just long enough to answer the phone? It was, she decided. Taking giant steps and missing all the cracks, she looked into the lit windows of the houses she passed, imagining the families inside. One mother was drawing her curtains as Ginnie walked by. She waved but the woman didn’t. Was she maybe the one who’d lost her child, and behind her a sad house, an emptied pool? Did she cry herself to sleep at night? The hair on the back of Ginnie’s neck prickled as she walked on, craning her neck back, pink tights light against the coming darkness. The mother closed the curtains, staying private.

Ginnie’s father wasn’t a private; he was a major, which meant that since they’d moved to the base, they lived in officers’ quarters (a house connected to four other houses in a line of many, many houses just like theirs, facing another line with a strip of grass and a sidewalk between). It meant they swam at the officers’ pool and had Sunday brunch at the officers’ club. Her father had medals for flying airplanes in the war and now he taught soldiers to fly; she wanted to learn too, but he said he didn’t teach girls. Ginnie aimed to fly anyhow, one of these days.

But here was a street corner, Jefferson and Sayres—she could read better than Kari, she’d heard her mother admit quietly, which had made her happy, and one day soon she might spill that secret to her sister. But right now, she had to figure out which way to turn. She went towards the lightness, humming under her breath and thinking about her mother’s secret, which was this: Mama was driving colored people around, and Daddy knew it, and Kari. Her parents probably thought Ginnie was too young, but she’d heard them talking about it one late night when she was listening at doors how she did when she couldn’t sleep.

She had heard Mrs. Solomon, too, when she’d come to talk to her parents about Mama’s driving for what she called the Officers’ Wives’ Taxi Service—OWTS— she said, like the opposite of ins. Mrs. Solomon was a Yankee, and Ginnie’s mother called her the smartest woman she knew. Her parents had talked about Mrs. Solomon’s idea late into the night and finally Mama said yes. Her father thought her mother was brave. Like he had been in the war, Ginnie guessed.

Like she was, now, finding her own way home.

The next crossroad was a big one—cars whizzed by, lights zipping white streaks—and when Ginnie read the street sign, she wanted to do a perfect circle flip on the spot. It was Carter Hill Road! Last year, her mother and father had gathered the girls in the living room of 475 Commodore Circle for a family meeting. Good news! her mother had exclaimed. An opening had come up in base housing and they were moving—right away, in two weeks!—and wasn’t it grand! She had clapped her hands, her voice excited. The schools were very, very fine and there was a pool and a rec center and things were different on base, just safer, and—

Kari had started crying then. It was the middle of the school year, she loved her teacher (which Ginnie knew she did not, but she did admire her sister’s quick lie). And oh, she said, her Girl Scout troop was going to Tallahassee next month and her science project was only halfway done and her boyfriend—but their father interrupted here and said boyfriends had nothing whatsoever to do with eleven-year-old girls and she’d best shape up and fly right and if he and her mother said start packing tomorrow, then that’s what she would do, with a smile on her face. Was that clear, young lady?

Kari said yessir and asked could she go to her room and Hannah started whimpering, even though she was too little to understand that they were getting ready to lose everything: again. Just like two years before, Kari told Ginnie bitterly, when they’d all had to move from Virginia to Montgomery, and before that from England. Kari had lost touch with her best friend Alice, from Virginia. They’d sent letters every day after they first moved, then every week, and now nothing. For all she knew, Kari said bitterly, Alice could be dead.

The next afternoon Buzz and Grace had to go to an important meeting about moving into base housing. The regular sitter couldn’t come, but they were going to trust Kari to look after her sisters for a few hours. This was a big responsibility, their father said, putting his hand on Kari’s shoulder. Was she up to it? Yessir, she said and they left. Ginnie went into her room and closed the door. Lying on the bed she shared with Hannah, she got thinking about how much she didn’t want to leave her friend Beth and their summer nights, about how she had no choice but to shape up and fly right. Then an idea came to her: She could take off now and hide out somewhere and, after the rest of them left, she could come back and live in the house.

This made her so glad that she started jumping on the bed. Kari came in and yelled. Ginnie told her to get out—she needed her privacy. Kari picked up the hairbrush and said she’d whip some privacy into her—her mouth got hard the way their father’s did—and Ginnie scrambled under the bed so fast that Kari couldn’t catch her, scrunching herself up in the middle and screaming one high-pitched squeal after the next, which crazed Kari; but she couldn’t reach Ginnie with the hairbrush and every time she started to push herself under the bed, flailing the brush, Ginnie scooted away and Kari would have to run to the other side and Ginnie would just move again, screaming all the while. It wasn’t hard. Her throat hurt but it seemed worth it. Kari finally threw the brush across the room and said Ginnie could go to hell for all she cared, which word Ginnie stored up (right next to the bitterness in her heart) as a secret to spill later.

Ginnie didn’t move till she heard the door click and Kari’s steps fade. She crept from under the bed to find a teary Hannah in the corner, sucking her thumb. I’m leaving, she told her, getting a bag and putting in underwear and pjs and—what else would she need—socks and the white piqué Sunday dress her mother had made for Kari that was hers now. And you can’t tell, she told Hannah, or you’ll go to hell.

Hannah looked at her with big fat tears in the corners of her eyes and that dumb thumb in her mouth until Ginnie said, Oh, all right, and put two shirts and a dress in the bag for Hannah. Okay kiddo, she said, let’s go. Kiddo was what Beth’s father called her; Ginnie wished her father had a silly nickname like that for her.

She could hear Kari’s voice on the phone complaining about her stupid little sister to one of her friends. She took Hannah’s hand and got the two of them out to the carport, where she settled her and the bag into the Red Flyer and set off down Commodore Circle. She made good time; they’d gone halfway up the slope of Carter Hill Road before Kari, breathless and red-faced, had found and dragged them back. By the time their parents returned, Kari had the two of them blowing bubbles out by the picnic table: a perfect picture of happy order. Everything had gone fine, Kari said, beaming. Later she’d given Ginnie fifty cents and said she’d kill her if she told. She hadn’t.

They moved to the base two weeks after that, and there was a pool and a rec center and everything was different. For one thing, they never had bomb drills where everybody had to dive under their desks and cover their heads, waiting for something they couldn’t quite imagine; for another, they went to school and church with colored people now (though they didn’t swim or eat brunch at the club with them). When Ginnie asked her father about the drills, he said nobody was bombing anybody around here; this was America. Her mother just said the airbase was a whole different world. How many different worlds were out there, Ginnie wanted to ask.

But here at least was a familiar one. She’d gone up Carter Hill Road last year when she ran away, which meant she should head down now, towards Beth’s warm house and her mother’s relieved voice on the other end of a phone line. Standing on the sidewalk as cars and trucks and buses whizzed by, Ginnie missed her mother suddenly. She could hardly believe her abandonment, but she knew it was for what Mrs. Solomon called a good cause. Pulling herself up, she headed downhill, into the glare of headlights.

The houses she passed were fewer now and less cared for. Ginnie didn’t recognize anything, and she almost longed for the safety of base housing. Ever since Christmas time, her parents had been talking about the trouble downtown. Crosses were being burned in yards; some colored people’s houses had been blown up and a white minister’s too; people weren’t acting human, her mother said. It made her ashamed to be a Southerner, she told Daddy, when he read her a letter in the newspaper that called for all the whites to rise up against the blacks, use guns and knives to kill them. It made her mother cry. What was the world coming to, she wanted to know. So now she was doing something about this latest trouble, which had to do with colored people who had to ride buses to get to work but had decided to quit doing it till white people started treating them like humans.

The yards Ginnie walked by now had scraggly bushes and peeled paint and old cars out front. Across the road shone no house lights at all, and soon Ginnie saw why: A lighted sign read Oak Lawn Cemetery; seeing that, she got a shiver all through. Dead people lay there, maybe thousands. Ginnie sped up. At the next corner she saw two colored women and a man. She walked past, looking down at the sidewalk cracks like her life depended on it. She thought she could feel their eyes on her. They didn’t like her. Who could blame them? She felt a hot, dark shame spread from chest to belly, its weight shorting her breath like she’d just done a triple flip.

The only colored people she knew beyond the ones she’d come across in first grade were her Aunt Cat’s maid, Sarah, and her little girl, Ruth. For three weeks every summer and a week at Christmas, her father drove the family to Gramma’s house for what he called RNR; that’s how Ginnie had gotten to know Ruth.

Most summer days, Ruth would come with her mother to Aunt Cat’s. Ginnie would wrangle an invitation and she and Ruth would play in the backyard or up in one of Aunt Cat’s guest bedrooms. Ruth, a year older, loved to tell stories. Ginnie’s favorites, the scariest ones, were about the Plat-eye, a haint-man who lived in dark alleyways and was especially partial to little white girls, and of Wish-plop, another haint who was forever dragging his legless black body after one little white girl who had stolen his treasure. The name came from the terrible sound the haint’s body made, first hoisting the weight up on its arms and pulling itself forward in a drawn-out whhussshhh, then the quick, soft plop of landing—all the while, his terrible eyes burning a hole into that white girl’s back. After a day of Ruth’s stories, Ginnie would dream at night the whhusshh-plopp of that body dragging its dark self up her gramma’s stairs. In dreams, she was always trying to give back the treasure, but she didn’t know what it was.

Sometimes Ginnie rode with her aunt to take Sarah and Ruth home. She wanted to sit in the back next to Ruth, but Aunt Cat made her sit up front instead; Sarah and Ruth always sat in the back. When Ginnie asked how come she couldn’t, Aunt Cat looked hard at the road up ahead and made a little clickety, disappointed sound with her tongue. Sarah and Ruth just looked out the window.

Ginnie liked the look of Ruth’s house, which had bright blue shutters that Ruth said guarded against haints. Your aunt should have some, Ruth said. The house sat in the middle of a row of other little wooden houses, each with bright-painted shutters, a tar-paper roof, and a sloped front porch with flowers and a rocker on it. Ginnie wanted to see inside, but Aunt Cat said no: Sarah and Ruth deserved their privacy. Can’t I just go over and play sometime, Ginnie finally asked, and Aunt Cat looked at her with pity and said, almost to herself, that she had no idea what kind of upbringing Buzz and Grace’s children had, never living in one place long enough to know the simplest thing about what was right. She didn’t invite Ginnie over for a week or so.

At the next corner, the street looked nothing at all like Commodore Circle, and down at the intersection Ginnie could see a group of colored people gathered under a streetlight. The road rose from there and beyond the rise shone a much brighter light that Ginnie thought might be the little downtown area where her family used to go to the movies. She looked behind her. How many blocks had she come? Was this even the hill she remembered? Back there loomed the cemetery; in her head she heard a soft whhussh-plopp, pictured a dark form dragging itself across the street to meet her.

Heading towards the lights, Ginnie was halfway up the block when a big city bus stopped right beside the knot of colored people. The bus doors opened—Ginnie was close enough to hear the whoosh of them—but nobody got on. The colored people turned their backs instead. Off stepped an old couple; Ginnie could see the lady’s white hair shining under the streetlamp; she held tightly to her husband’s arm. Keeping their backs to the bus, the group parted to let them pass. After the white couple walked off, the bus doors stayed open, then Ginnie saw a silvery something fly out from the open door. A colored man shouted and slapped his hand to the back of his neck. He lunged towards the bus; the others held him back, and the bus doors closed.

Ginnie had only five or six sidewalk cracks between her and the group now, so she heard the man say Shit! while he wiped his neck with a handkerchief and she heard the others saying, He gone, Sammy; let it go, Sammy; hush now. She thought of the darkness behind her and the man in front of her who’d just been spit on and she kept putting one foot in front of the other, looking down.

When she was almost to them, everybody stopped talking. Ginnie was afraid to look up—how would she treat the next white person she met after being spit on? She stared down at her pink tights and the straps of her black dance shoes. She imagined flipping herself rapidly, end over end, right through the middle of these people and on down the sidewalk towards the lights, like the tumbleweed she’d seen in a cartoon.

She was in the middle of them now and into her down-turned vision came a man’s brown-shoed foot and a lady’s creased black flat, the toes turned slightly up. Ginnie sidestepped towards the grass but found more shoes there—some sneakers and a lace-up. She looked up into a sea of black faces. The ladies wore hats or scarves and both men had on glasses, so she couldn’t see their eyes—she couldn’t see anything but the outline of dark heads with the streetlamp lighting the night above them. She was encircled. She squeezed her eyes shut. Whusshh-plopp: she heard. The hot, dark thing that had slid from chest to belly moments before rose now, right into her throat and out, into a piercing wail.

The crowd around her broke away at the sound, people rocking backwards like they’d been shot. A path cleared. She was free to go—and she meant to, but her legs wouldn’t move. She crumpled into a pink heap, tears scalding her cheeks. She wasn’t brave at all, she saw; she couldn’t fly, or even walk.

Ginnie felt a hand on her shoulder. “What’s wrong, child,” came a soft voice, near her ear. “Where you headed, this time a night?”

“Leave her be, Esther,” came a rough voice. “Let her get on past. No trouble—that’s what y’all told me. No trouble, which this is. Let be now.”

Ginnie saw the colored man who’d been spit at: Sammy. He might spit on her now, the way his mouth was twisted. Instead, he looked at her without blinking and said: “Get yourself on home, little girl. Too late for one a y’all to be out on these streets.”

No one else spoke. Ginnie stood on wobbly legs. She took two steps before the choking thing in her throat rose again. She was lost forever; she saw that now. She couldn’t turn around—behind her were dead people and colored people; in front were the lights, which she might never reach.

“I just want to go home,” Ginnie wailed, and the sobs she’d held back came in a gush. She stood with head bent, hugging her bag to her chest. When she felt a hand on her shoulder and the same soft voice calling her child again, she looked up into the kind face turned down to her. The woman wore a small, dark hat set close on her head and a sweater buttoned against the evening chill. When she put a hand on Ginnie’s arm, it was gloved and soft. “Please, can I go home?” Ginnie croaked.

She’d no more spoken the words when a car pulled up to the curb. The woman turned to look, as did Ginnie. It was a huge black station wagon with silvery chrome shining down its sides. Ginnie blinked, her mouth gaped open. It was one of those cars dead people rode to cemeteries in, she thought, and the fear emerged in a squeaky gasp, at which the woman said, “Hush, honey, nothing to be afraid of; it’s come for us”—which did not at all relieve the tight knot of Ginnie’s fear.

The door next to the sidewalk opened and a man’s face loomed out over the passenger seat, his darkness gleaming inside the dark of that black car—a hearse, they called it, like the one that had carried her great-uncle Franklin to the Red Hill Presbyterian cemetery last year.

“Y’all ready?” he asked. Another whimper escaped; the woman brought her face level with Ginnie’s so she could see into her eyes, which had nice crinkles at the corners.

“Hush, child,” she said, “this ain’t nothing but our rolling church.” Then she raised her voice, like she was talking to the whole bunch, though she kept her eyes fixed on Ginnie’s. “It’s our rolling church, honey, that’s gone get you home, and us, too.”

After that the woman left her. Ginnie kept her shoulders hunched against the cold. She heard tense whispering, a word or two: white child, trouble, just plain fool, Esther; black self in jail; but the last words she heard were Esther’s: Do what’s right. Things got quiet and then the woman led Ginnie to the back, where the door was swung open wide. Inside, Ginnie saw folding chairs lined up against the sides.

“Step right on in,” the woman told her. When Ginnie didn’t move, she bent again. “What’s your name, child? Mine’s Esther. And where is home?”

Ginnie had not a minute’s hesitation; she felt stronger even as the words left her mouth: “475 Commodore Circle.” She stepped into the darkness and took the seat Esther pointed out, in a chair backed up to the window separating the front and back seats. In her head she repeated 475 as the hearse filled up. Some of the colored people didn’t get in. Sammy and two women stood by the curb; Ginnie saw them shaking their heads. Esther spoke to the other passengers as they got in: “Come on through, Miss Nettie,” she said, patting the chair beside her; “Okay, Jess,” leaning across to touch a knee. Everybody seemed to soften when she spoke their names: “Deb and Verna, y’all good? Henry, sit.” Henry was the last in; he took his hat off as the driver swung the door shut and the inside went dark and quiet.

The driver—Benny, Esther called him—spoke to the three left outside, pointing to the empty passenger seat. They shook their heads. “Take it easy then,” he called. “Stay safe.” Then the door shut, and the world Ginnie knew was outside and she was sitting in a hearse full of colored people she’d never seen in her life. She didn’t feel like crying anymore, maybe because she was warmer and not trembling so hard, or because Esther was humming a soothing little something under her breath.

When Benny said, “Where to, Esther,” and she answered, “475 Commodore Circle,” Ginnie felt safe and almost happy. And suddenly starving. Just when she thought that very word, here came Esther’s hand holding a small, red apple. “Hungry, child?”

She bit and it was sweet; she tried to chew quietly. She listened as Esther and Benny talked back and forth about how to get to Commodore Circle. “This ain’t exactly my part of town,” he said.

While they rode, Ginnie glanced sideways at this face and that. The woman called Deb rocked some on her chair, pursing her lips without making a sound, and the man Henry moved his hat round and round in his lap; Miss Nettie’s eyes stayed closed. Benny stopped once to look for a map in the glove compartment but couldn’t find one.

“Why’s a hearse gone have a map, Benny,” Esther said, and they laughed quietly. But Benny stopped in midstream and said, “Cops.” Esther pulled Ginnie towards her, covering her head.

“Oh, Jesus,” moaned Deb, rocking harder; Henry’s hat made faster circles. A siren sounded: the hat stopped dead and other voices joined the Jesus chorus. Ginnie smelled her own rank fear, mixed with theirs.

Then came Benny’s voice, shaky: “Okay, okay. Look like the man got other business on his mind tonight, y’all.” He laughed again, but not like anything was funny.

Esther let Ginnie go and asked, “Where are we, Benny?” He took one more turn and answered, “Why, at Commodore Circle, Miss Esther, don’t you see that?”

The next minute he’d stopped and inside the car went completely quiet as Ginnie looked out at her old house sitting in darkness next to Beth’s, which was dark, too. The streetlamps shone on 475’s raggedy lawn with its sign: For Rent. The Millers’ house was dark, and the house next to theirs. Looking at all that emptiness, Ginnie felt her heart give a lurch as she remembered: It was spring break for Forest Hills. Beth was probably in Pensacola, the Millers in Atlanta. She remembered last year, the way the neighborhood had emptied out like a ghost town.

Her legs took up a shaking as she tried to stand. “Thank you for the ride,” she whispered, hoping politeness would propel her past legs and chairs.

Esther’s hand stayed her. Why had Ginnie brought them here, she asked softly. Why had she told them a story? The questions dropped Ginnie back into her chair. She covered her face and moaned, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry; I just wanted to go home.” She rocked herself a little, like Deb.

“Where is home?” Esther asked.

Ginnie said, through her hands, “I can get out here and walk.”

Esther asked again, her voice tired but still kind, and “1341 Lee Street” popped out of Ginnie’s mouth.

Benny put the car in gear, and they rode through quiet neighborhoods for what seemed like hours. Every time car lights came up behind them somebody sucked in a sharp breath and Deb rocked faster. Once a pickup pulled up next to them at a stop sign, and Ginnie got a glimpse of a white man’s face, flat and unsmiling, scarier than any Plat-eye. Benny didn’t turn his head; Henry circled his hat. The truck gunned by.

The car turned and turned and the silence grew so thick Ginnie thought she would explode. She wanted terribly to fill it with talking, to tell everything, even private things: about her father’s flying and the feel of his hairbrush on her bottom when she was bad; about her mother’s bravery and the way she cried sometimes at night, alone, on the living room sofa; about Wish-plop and the Plat-eye and Ruth’s bright shutters; about the hateful newspaper letter. But she could only think these things; they would not come out of her mouth.

Now they were parked in front of Miss Lily’s and Ginnie said, “Thank you for the ride,” and this time Esther didn’t stop her. The back door opened. Ginnie saw sneakers and flats and brogans as she got out, clutching her bag against her thumping heart.

“Thank you,” she whispered again as the hearse pulled away. Nobody said, you’re welcome, which she knew she didn’t deserve anyhow.

Ginnie looked down the street and up at the mystery of Miss Lily’s house, too dark to penetrate. She sat on the curb, the chill of which she felt instantly through her tights. She would wait here for morning, she thought. Someone would come looking by then. She imagined her mother crying over her lost daughter and her father tearing around in his car searching for her, Hannah sucking her thumb and maybe even Kari worried.

Ginnie moved to the damp, cold grass between the curb and sidewalk and laid her head on her bag. Shivering, she turned on her side and curled up, thinking about the colored people in the hearse. Maybe they lived in little leaning houses like Ruth did.

Once, she’d asked Ruth what she did when they weren’t together. Nothing, Ruth had said. But Ginnie insisted. Did friends come over, did her mama make big Sunday dinners, where was her daddy? Was her brother James sweet to her, or mean, like Kari? Don’t know, was all Ruth would say; funny, how she would tell haint stories all day long but never offer up a one about her own self.

Now Ginnie pictured Miss Nettie at a stove cooking up shrimp creole like Sarah did at Aunt Cat’s, the smell filling the house; she saw Henry playing catch with his boy in a little dirt-raked yard, Deb in a front porch rocker, Verna hanging laundry. Esther she imagined in the choir section of a big church, humming something rich and low. In the midst of shivering, Ginnie’s eyes grew heavy with imagining.

She didn’t hear the car at all, only felt a hand on her head and heard a voice calling, “Ginnie, Ginnie,” and thought it was her mother’s till she opened her eyes to find Esther. A minute later, the two of them were sitting in the front seat, next to Benny. The back of the hearse was empty now. The heat was turned on full blast and the air of it made her teeth chatter even harder. Her body was cold to the bone. Esther rubbed her shaking hands, saying, “Hush now, hush.”

Ginnie didn’t, though; instead, she broke down again, crying until her face was hot with it. When her shudders finally stilled and Esther asked her once more where home was, Ginnie said they lived on the base.

The car fell silent. Esther and Benny looked at each other and she said, “Benny?”

He shrugged. “Too far in to back out now, sister.”

The ride to the base was quiet. At the gate, Benny pulled to the side and sat, taking deep breaths. Esther put her hand on his and they looked at each other. Then he got out and walked to the MP booth. Watching his departing back, Esther closed her eyes.

After that, things happened fast. An MP got the two of them out of the car and took Ginnie off to a little room by herself. Somebody brought a blanket and soon her mother showed up, crying and glad, just like Ginnie had imagined. Her mother didn’t ask much, just took her hand and they walked outside, where Ginnie saw her father standing next to three MPs and Esther and Benny off to the side with more base policemen standing beside them. Even though Esther was holding herself straight as a ruler, Ginnie saw right away how small she looked beside those men with their white hats and dark uniforms, guns strapped into holsters. Ginnie looked at Esther and Esther looked back, and in the space between them passed something sad and mysterious. Esther looked away. Ginnie’s throat closed and then opened; she pulled her mother down and told everything that had happened, fast. Ginnie’s mother called her father over and she told it all again, gulping for air. Afterwards her father said nothing to her, just talked to the MPs and then went over to Benny and Esther. When he shook their hands, he looked stiff and formal, like at Uncle Franklin’s funeral.

Ginnie wanted to say goodbye, but her mother held her shoulder tightly, saying those folks had likely seen about enough of her for one lifetime, so she just waved as they took off in their big black car. The last thing she saw was the chrome catching the light, so bright she had to shut her eyes against it. She’d remember that for years: Esther looking away, that shiny chrome, her own closed eyes.

When her father returned, he slipped one arm through her mother’s. Following them, Ginnie could hardly walk, her legs had turned so heavy. As the car door closed, she felt the world click into place, almost like she could hear it. When they got home, she didn’t get the hairbrush or restriction, though she missed supper and it turned out that the trips to Miss Lily’s were more inconvenient than ever, so she had to quit acrobatics. Grace quit her taxi service, too. Best stick close to home, her father had said, later that night. No need to call attention to ourselves. We are base people now.

On base, at five o’clock every day, the sound of Retreat filled the air. Cars stopped in the road and people quit talking or walking or even thinking and put their hands over their hearts. Celebrating our country, her father said: Stand proud. Ginnie would do this for years, until it came as natural as breathing; listening, she would feel something she couldn’t name, a weight that made her eyes sting. Later she would give it a name: shame.

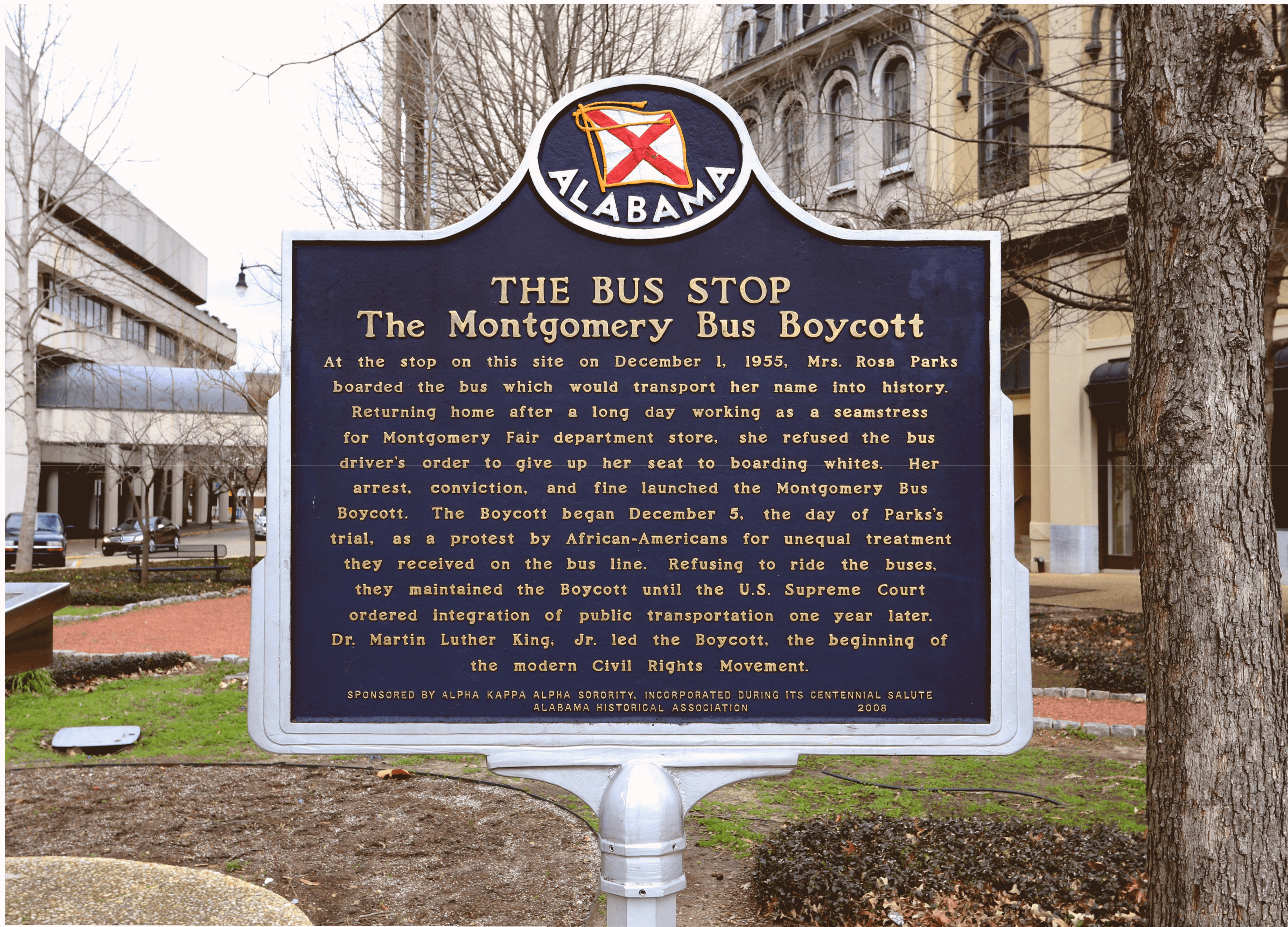

When Ginnie thought about that night, she would hear Benny’s deep voice, trying to joke; she would remember Esther’s kind hands and the humming inside her. Much later, when she read about what Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King had done, it was Benny and Esther’s faces she saw in her mind; she remembered Miss Nettie and Deb, Verna and Henry; Sammy, too.

When the family told stories about that day in 1956—as they told stories about everything in their lives, embellished through the years—her mother would call it Ginnie’s little adventure, or the first time Ginnie ran away. But Ginnie never saw it like that: She’d only been trying to find home; sometimes she thought she always would be. And it would be years before she’d remember wanting to fly.