Excerpted from the author’s memoir, My Persian Paradox.

One June day of my freshman year/ninth grade, in 1985, I needed a break from studying. My mother suggested we go out for ice cream to Tajrish Circle. Tajrish, a shopping area on the skirt of the mountains in the northern part of Tehran, was a favorite place for my mother and me to wander, especially for window shopping and mouthwatering snacks. My father disagreed. “Afternoons are the worst time to go to Tajrish. There will be no parking spots. It’s hot outside. Why don’t we just stay at home and rest?” To my mother, he grumbled, “You take advantage of her, suggesting ice cream to satisfy your own childish desires.”

I felt terrible that a fight was starting again because of me and said, “Baba, I said I wanted ice cream. Can we go to Tajrish, please?” I didn’t mind going out for ice cream.

Grudgingly, he conceded. I jumped to my room and carefully chose my white scarf to overcome the ugliness of my loose and long black mantou I had to wear to cover myself from shoulder to toe, thinking my red nail polish looked good with white and black.

In June we had an exam every couple of days but didn’t have to attend school otherwise. The time between exams was an excellent opportunity for Negar and me to polish our nails, but we had to be careful to remove it entirely for the exam day. If the school staff saw any remnant, our discipline grade would bring down our GPA. If Basij (Moral police) saw it in the street, even worse. So, we made a ceremony of polishing our nails after each test and removing the polish carefully before the next one.

I had gotten a short haircut a few days before and had blow-dried my hair. Standing in front of the mirror, I carefully put my scarf on and brought a few strands out, making bangs on my forehead.

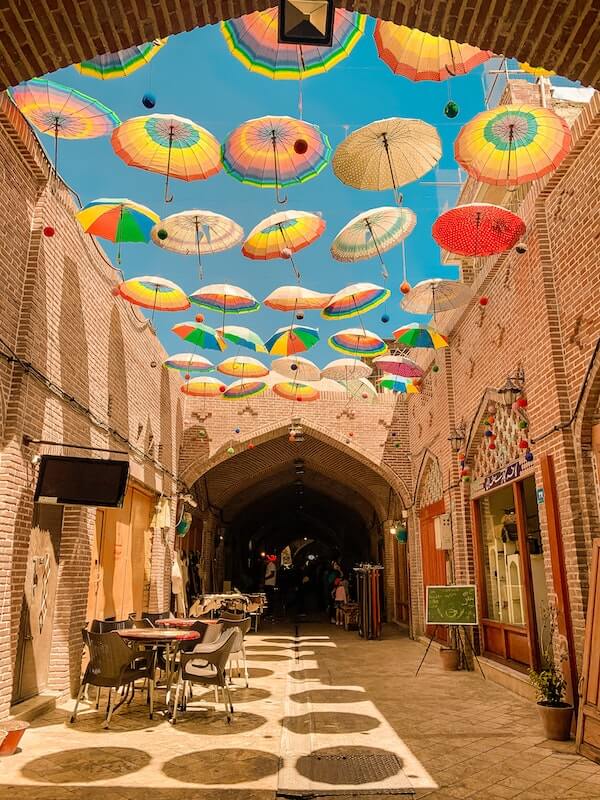

Tajrish Circle was always crowded by shoppers who enjoyed the mixed atmosphere of modern boutiques with a couple of mannequins wearing fancy dresses looking at passersby and traditional spice shops with the barrels of colorful spices all lined up in front of each shop. In the southern part of the circle, inside the covered Bazar with narrow alleys, traditional grocery shops hung out beads of vegetables, and decorated bunches of herbs. They set arrays of fruits on big-wheeled tables outside of their shop. No one was allowed to touch the fruits. The shopper picked them up upon the customer’s request with some stiff gestures that felt like he was giving his possessions away for free. Everything together made a lively picture, fun to watch. We never bought groceries from there. They were expensive.

As Baba predicted, we did hit a lot of traffic. At that time of the day, it took us almost forty-five minutes—three times longer than it would have taken if it wasn’t rush hour. It was hot inside the car. My father’s face hardened. He made frustrated noises: “Aaahhhhhh I told you.” Sitting behind my father, I looked out the window, afraid my mother would snap at any moment and scream at him. I knew it was getting close to the time my father needed to drink his vodka too. That could only happen at home since alcohol was banned and not sold legally in the street. If it was late, he would become violent.

We passed the main round about and got to the beginning of Pahlavi Street. The tall old trees on both sides of the street had brought their heads together to make a comfortable shade on this longest street of Tehran. We started to look for parking in front of our favorite ice cream shop, Ladan. Saffron ice cream with big chunks of frozen cream was one option; chocolate, vanilla, or strawberry flavor were nontraditional options, called “Italian ice cream.” I was daydreaming which one I wanted to choose that day.

We were all looking desperately for a parking spot since my father’s attitude was becoming intolerable when all of a sudden we heard a voice in a megaphone behind us shouting: “Red Peykan (a type of car), red Peykan pull over.” A white SUV carrying four Basiji pulled close behind us. During the summertime, they were coming to catch people a lot more often than in the wintertime. My mother and I immediately covered our hair completely. My father pulled over, not all the way, almost stopping in the middle of the busy road, and they stopped behind us. Two women wearing black chador (a long head-to-toe scarf) in such a way that I had a hard time seeing even their eyes came to our car and opened the back door. They shouted at me to get out and directed me to the SUV. My parents jumped out of the car. The women pushed me into the SUV’s backseat and jumped in with me. My mother stayed in front of the car in case they tried to drive me away.

The women started yelling: “Shame on you having red nail polish! What did you think!? You followers of Westerners. You betray your own Islamic culture following the sinful Western culture. Don’t you respect the blood of martyrs in the war against Iraq and the West? They are dying for us, and you worthless girls are thinking about red nail polish?”

The Basiji woman handed me nail polish remover and cotton balls. I had heard they used poisonous chemicals in the nail polish remover. Scared and hesitant, I cried and removed my nail polish with shaking hands, wondering how on earth they had even seen it inside the car. She said my black hair against my white scarf had caught her attention. Most likely, while I was covering my hair, she saw the nail polish.

My father talked to the Basiji driver, who seemed to be the leader of the team. My mother came to the window of the back door and begged the woman on my right to release me, promising I would never do it again. She was ready to cry, asking them: “Please release her.”

Meanwhile, a police car arrived, and an officer warned my father to move his car, which was causing more traffic. The woman next to me rudely told my mother to open the door. She got out and told me: “I know you go to school around here. If I ever see you like this again, you will go to jail instantly.”

I jumped out of their car, shaking, and took my mom’s hand. The woman faced my mother: “It is all your fault you let your daughter be seen like this. You are careless parents promoting bad behavior.” My mother dragged me to our car, and we jumped in. I was shaking while my mother yelled at me: “Why did you have to polish your nails?” I cried quietly. They could have taken me to jail and given me lashes. I could have missed my final exam.

My father made a U-turn in the middle of traffic, and we went home with anger, our only ice cream, the flavor of tears. We were all silent in the car, but of course, my parents fought violently when we got home.

I went to my room to avoid their fight, and feeling guilty I caused it, crying until I fell asleep. The humiliating tone of voice the Basiji women used stayed with me for a long time. Negar and I stopped the ceremony of nail polish wearing and removal between our tests. For a few days, I covered my hair under my scarf carefully. But, soon, it came out again; Universal desire for freedom.