Our brightest days are a rich subset of a broader story and the fortunate among us ration a few for the end, savoring them as that final nightfall advances. Petrakis appears to have plenty of life left in him, but his stock of unclouded days is depleted. Nora, his bride of sixty-two years, passed this summer and the combination of his memory outages and the solitude that her absence compels is more than the old man can manage. Nora’s death greased the slope of her husband’s steep decline.

Petrakis was sprite when I came over to fix his breakfast. And he was drunk. I check on my neighbor several times a day and I am supposed to report his condition to my parents, but doing that will only quicken his exile to assisted living. I do his laundry, shopping, and cooking, I tidy the house and yard, and I even bathe the old-timer on Saturday afternoons. Mostly, though, I say nothing to anyone about his situation. My parents will catch on soon enough, and until then there is little I won’t do for my friend.

“We need another bottle,” Petrakis said. He set the empty beneath the table and smiled up at me.

The way alcohol thickened his Greek accent never failed to shake a grin from me. “I’m fixing coffee.”

A wondering look drifted into his eyes. “Do I smoke?”

He burned through a pack a day all the years I’ve known him, until last July when he simply forgot about the habit. Telling him anything but the truth would never be an option, so I said, “You told me once that you’d kick my ass into next week if you ever caught me with a cigarette.”

“Huh.” He studied his fingertips. “Seems like a smoke would be nice just now.” My battered knuckles snagged his attention when I set the coffee out. “What the hell?” He is deceptively quick and caught my wrist before I could retreat. “For Christ’s sake. You don’t know better than to get into a fight?”

Petrakis has been my confidant since my mother and I arrived from Russia eleven years ago. The fact that we each left our homeland as children is the basis of our bond and the disappointment in his voice made my heart ache. “This smartass at school wouldn’t stop making Putin cracks.” He shook his head, not following me, so I explained, “Like how you told me that back in the fifties kids called you a Communist because you came over from Athens.”

He watched me and I couldn’t say if he’d drifted again or he was taking this apart in his mind. “I slugged anyone who called me a Communist?” He sounded curious, like he didn’t know.

“No, sir.”

“There you go,” he said, leaning back. “And what should you have done?”

I fidgeted before answering. “You always tell me to stand straight and deal with whatever comes at me.”

Petrakis reached to his shirt pocket for absent cigarettes and fingered a piece of yellow notepaper he’d been carrying around for a week. “Stand straight?” I nodded. “How can you manage that with your head up your ass?”

“It’s not likely that I can, sir.”

We both smiled, though a lost look swept his face. “Who are you again?” he asked. That question never got easier to hear. His eyes widened. “Peter?”

His son was killed in Vietnam. “No, I’m Nicholas.”

He nodded but there was no comprehension in his gaze. “Call me Gus,” he said, and he tucked the note away. My guess is that it’s another of the memory jogs he’s been taping up around the house recently.

He frowned at the coffee and pushed the mugs to the center of the table. Petrakis is a month short of eighty-three years and though his mental capacity is in retreat, his physical condition hasn’t surrendered any ground in the time I’ve known him. He rose from the table with swift agility. “I’ll get the wine.”

“It’s morning.” I pointed to the window. “That’s daylight out there.” Petrakis stepped to the living room without turning back and I checked the wall clock; by now my mother would be waiting for me to take her to church. “Mr. Petrakis… Gus…” I’ve never called him that and the sound of the name coming out of my mouth—a single syllable that gets the job done without messing around, just as he once did—pleases me. “Gus? I have to go.”

“Who the…?” He poked his head back into the kitchen, a startled stare etched onto his face, and ducked away again.

I stood to check on him. “Mr.—”

Petrakis turned the corner with a shotgun levelled and I dropped to the floor as he tugged the trigger. The blast was deafening in the little kitchen and it blew out the window above the sink. It also tore away a chunk of cabinet to the left of the window and a shelf inside tilted, causing half a dozen glasses to slide out, one after the other, and crash to the tile countertop.

I bolted to the yard and rounded the corner of the house, cradling my right hand in my left. The fourth and fifth fingers were misaligned—I must have hit something on my way down to the floor—and they raged with pain, which spiked red when I plugged them back into place.

Petrakis yelled from the kitchen, “Who the hell do you think you are coming around like you own this place?”

“Goddammit, it’s me. It’s Nicholas.”

The gun blasted again, this time out the back door, and I ran.

I stepped out of the church basement and into the sunlit parking lot, where the parish men had divided into two camps. The first was paying its respects to a dead air conditioning compressor at the back of the building, burning off-brand cigarettes for votive candles, and the second was gawping into the engine compartment of a prehistoric minivan.

I was six when Mom and I left Saint Petersburg, and I’ve spent the ensuing years in Virginia’s public schools, where the agitation of American living eroded the footings of my Slavic heritage. My mother tries to shore up the damage by lugging me to the Saint George Orthodox Church in Manassas on Sundays. The congregation is a montage of displaced innocents mostly from Central and Eastern Europe who gather for potluck lunch after services, and while I endure these immersions for my mother’s sake, I will never share her nostalgia for anything we left behind.

The smaller kids swarmed the playset as I passed them on my way to the back of the lot, where the high schoolers stretched out on the weedy lawn. “Here comes our American,” Igor Sokolov said. He leaned against a chain-link fence with Rada, the new girl from Serbia, at his side. She’s friendly enough, but seeing her wedged against Igor made me wonder if there might be something defective in her judgment. “Mamochka sent you to play?”

It burns me that he got that right. My anxiety over the disaster with Mr. Petrakis earlier was still bubbling and I wanted to skip lunch and race to his house. Badgering Mom on that point did me no good, because she lost her patience and ran me out of the cafeteria. Had I bothered to share with her the details of my morning misadventure, she might have cut short her gossiping with the choir director and towed me home by my ear.

Rada stepped forward. “What happened to your hand, Nikolai?”

My fingers had swelled notably. “Football injury.” Plausible, I thought.

Rada was pretty but her thin frame was only a couple of missed meals short of deprivation. “You play on your school team?” I nodded that I do and she raked her fingernails out from my palm to my fingertips. “American football?”

I offered up another stupid nod. I can do this all day.

“Does it hurt?”

“You don’t watch movies, Rada?” Igor cut in. “Nothing hurts American hero.” His language skills were lacking, but English is the group’s common tongue and he’d butcher it before he ever held his own. “He plays baseball, too. American sport for American hero.”

Rada smiled, not breaking eye contact with me. “And what’s your game, Igor?” The silence drew out and her grin spread like a spill as she addressed me again. “Your hand is so rough.”

My face grew hot and I pushed away. “We run a dairy.”

“Don’t get excited, Rada,” Igor said. “He has American girlfriend, too. No immigrant trash for our Nikolai.” He threw his arm over her shoulder, marking his territory.

Rada blushed a furious shade of scarlet, prompting me to wonder why the Igors of this world can never stop flapping their mouths. A pair of girls from the group scrambled to her aid and shuttled her off as I stepped in tighter, but a Ukrainian kid named Taras caught my shoulder and held me back. At school I’m too Russian and here, too American. The girls reached the church door as my mother stepped out with two other women. I patted Taras on the back. “See you next week.”

“Hurry to Mamochka, American,” Igor said. “She wants to get home to your Internet papa and—”

I delivered a jab to Igor’s jaw that dropped him to the lawn like a sack of bottles. His body convulsed twice before coming to rest and the group stared in hushed awe, a counterpoint to my mother’s scream. Someone summoned the priest, who got Igor to his feet and quieted the spectators, but my mother couldn’t stop trembling. Once settled into our car, she asked, “What you were thinking, hitting that poor boy?”

If I had been thinking, we wouldn’t be sitting here talking. “It won’t happen again, so leave it alone. Please.” I absorbed the scowls of the reassembled congregation as we motored past them on our way out of the parking lot. Everyone but Igor watched, and no one but Rada smiled.

I lifted a baseball cap from a hook at the kitchen door and my mother smacked her wooden spoon to the countertop, spattering gravy up the backsplash behind the stove. “One time.” She turned down the heat on a burner. “I wish you would do one time what I ask, Nikolai. I told you to shower before you go.”

“I need to talk to Mr. Petrakis. We’ll be a few minutes, then I’ll bring him here and clean up.”

I couldn’t check in on Petrakis when we got home because my stepfather, Matt, called me up to the workshop roof, where he needed help patching a leak and where he got fatherly over the fact that I’ve been involved in two fights in three days. Standing now in the kitchen with my mother staring me down, my distress slipped out as a stinging in my sinuses and my eyes welled. Mom extended her arms the way she did when I was a kid and one of us had offended the other. I hugged her, feeling too old for this, yet still yearning for her closeness.

She’s tall but has to look up to meet my eyes. “Take your shower, sweetie. Then bring Mr. Petrakis for dinner.”

“I have to go now.”

Hands to hips. “Why do you argue like an American teenager?”

“I’m an American and I’m seventeen. What do you want from me?”

The hardened glint in her eyes told me that what she wanted was for me to shut my damned mouth and do as I was told, but Matt ambled in and distracted her on his way to the fridge.

“Dinner is ready.” She held up a hand to block the refrigerator door and told me, “Get Mr. Petrakis. I want you at the table in five minutes.”

“Are you going over on foot?” Matt asked. I confirmed; walking was quicker than driving all the way around and Petrakis enjoyed the trek home after dinner. “Gus was cloudy when we spoke earlier,” Matt said, “but I had to close up the roof ahead of the rain, so I couldn’t get over there. Drive him back in his pickup if he isn’t well.”

Sure, right after I board up the window and stash his empties. I agreed and hustled out and across the yard and passed through the wire fence, careful not to snag my shirt on the barbs. I dodged cows across the upper pasture, cutting into the copse of trees bordering the place as my imagination reeled out renderings of mischief the old man might have stirred up while he was left alone.

I paused at the top of the hill where the properties abut and where Petrakis’s house was visible through the branches. Beech and oak commingled above me and scattered a mosaic of shadows too feeble to mitigate the oppression of the late season humidity. The heat had reached its peak for the day, that point where the mugginess and my patience to tolerate it met in a standoff before backing down for the evening.

I entered the clearing where Mrs. Petrakis once kept her garden and the house, a brick matchbox dwarfed by the barn looming in its background, came into view. The place was peaceful but the barn door, always open, hung nearly closed and a narrow rectangle of darkness lurked behind it.

Sweat beaded beneath my hat, which I removed to blot the moisture away with my forearm. The humidity was a living thing today, quelling even the hymn of the cicadas. Matt had been right; rain was coming. Petrakis always had a cold root beer at the ready on days like this, but those times have passed and that truth brought a chill that shimmied across my skin like a clutter of spiders.

I broke for the house and hurtled up the back steps and into the kitchen, where the shotgun rested on the table. A horsefly buzzed a circle around the room, then jigged right and flew out through the busted window. Broken glass crunched beneath my shoes in the kitchen and the odor of spent gunpowder, faded but stubbornly present, greeted me in the living room. I lifted a notepad from the coffee table, another of the checklists Petrakis had begun scribing in his effort to compensate for the faulty wiring of his memory.

Pay Washington Gas, the first entry read. Feed Scuttlebutt, the next. I choked up a little on that one; the old retriever fell to a copperhead bite six years ago. Take Nora to beauty parlor. The tears rolled when I saw the line drawn through that final item. Clarity apparently revisited Petrakis long enough to make him suffer the loss of his wife all over again.

At the stub of hallway leading to the bedrooms, I called out for the old man. Nothing. The bathroom was also empty, so I hurried out of the house to the barn, leaping over one of Petrakis’s boots lying along the path. I pushed the barn door open and its arthritic wheels squealed as they labored across the rusted iron track. Petrakis lay sprawled like a rag doll fallen from a shelf, the second boot sitting upright at his side.

I retrieved my telephone from my pocket and called Matt. “He had a heart attack or something. He’s dead.”

“I’ll be there in two minutes.”

Drawing in a constricted breath, I stepped to the body, where an ant marched across the face and Petrakis didn’t flinch. Dust coated his socks, one of which had slipped far enough down to expose his heel. “I can’t leave you like this,” I said, knowing I’d take an ass chewing for messing with the body.

The barn had a decade’s worth of the sort of debris that accumulates on a declining farm—busted implements, shelved tools and enough tractor parts to fall just short of aggregating to a functional machine. The autopsy of an ancient chainsaw lay on the workbench coated in grime, and the damp recollection of moldering hay loitered all around. I saw no tarp or blanket to cover the body.

Petrakis reeked of dried sweat and urine, compelling me to hold my breath. I lowered myself to the dirt floor and pulled up the socks before drawing him into my lap, then cradled my friend’s head. I fixed his hair and leaned in to touch my lips to his stubbly cheek. The Greek was a kisser, especially after he’d been in the wine.

I imagined him giving me grief over the trouble I caused at church, responding in the irritated voice he contrived for that sort of a dressing down. For Christ’s sake, the bastard’s doomed to be a foreigner the rest of his days and you kick him in the nuts because he resents how easy life here is for you.

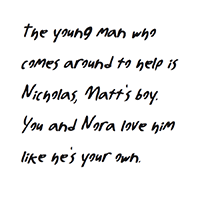

An icy wave of shame washed over me and I slumped. My hand came to rest on Petrakis’s bony chest, where it caught the fold on the slip of paper in his pocket. I pulled the note and read the unsteady hand:

I tucked the note into my pocket as the familiar hum of tires on Matt’s slowing pickup made its way into the barn and the faint but growing wail of sirens cried in the distance. The rain finally came, tapping out its tune of relief on the tin roof overhead. I kissed the old man’s forehead and laid him out, imagining away the alarmed stare locked on his face. I smiled down on my friend and stood straight, braced to deal with whatever comes at me next.