On our way to the family reunion west of Yorktown, Texas, we stop at Uncle Anton and Aunt Frieda’s house. Inside, my sister and I wander among the tumbled syllables of German. It is a language we can no more comprehend than the calls of cows and sheep and chickens. But like the farm sounds that daily surround us, the words our elders speak together, claiming their ties, ease and comfort us. These are the right sounds for kin to make together. Afterward, we take Daddy’s hand; he walks us out into a barren, fenced backyard and to the door of a much smaller house standing alone, unpainted.

The door creaks open. We are inside something much older than the sound of kinfolk speaking German. The room smells of black wool and pipe tobacco, cedar chests and mothballs, musty magazines and books, old air, old body odors, other tinctures beyond naming.

Judi was four then, going on five. She took the first turn on our great-grandfather’s lap while I waited. Three and usually full of words, I was awed though not quite frightened, curious really—struck by the riddle of time that might one day transform me into a very old man, a very lonely old man, having outlived everyone else. The flipside of a child’s wonder is a kind of all-encompassing, unblinking acceptance of things as they are. Yes, my moments in the little house enthralled me. At the same time, as is so often the case with children, I took these visits entirely for granted. I didn’t wonder why my great-grandfather was living in a separate house in someone else’s backyard. This was just the way things were.

While Opa held us on his lap, Daddy practiced what little he could remember of the Platdeutch his mother’s father had brought from the old country. Wilhelm Bruns by name, Opa was thirty-eight years old at the dawn of my own century. By the time my sister and I were taken to his little house in the backyard at Uncle Anton and Aunt Frieda’s, he had the weather marks of nine decades—white hair and beard, stooped posture, deeply wrinkled face and hands protruding from an ancient black wool suit that made him look ready for the casket. Opa spoke no English at all, but he didn’t need words to express how much he loved these visits from his toddler descendants. He was happy having us in his lap, touching us lightly—cheeks, pate, fingers—while Daddy talked.

Wilhelm Bruns died in 1953. He was ninety-one; I was not yet five. In the decade that followed, I grew close to his daughter, Lillie Bruns Meischen, whom we all called simply Grandma. One afternoon about midway through high school, I was sitting in her living room when memory struck—and along with it, the oddity of a great-grandfather who lived in a little house in the backyard on his son and daughter-in-law’s farm.

“Grandma,” I said, “what on earth was Opa doing in that little house in the backyard all by himself?”

“Now there’s a story,” she said.

In 1929, Grandma moved, with her husband and three sons, from the Garfield community west of Yorktown, Texas, relocating ninety miles south to a small farm in the brush country stretching inland from Corpus Christi Bay. By then, Opa had been a widower for almost three decades. The plan was that he would move with Grandma and her family. Opa didn’t say otherwise until the day of the move itself, when he refused. At sixty-seven, he’d lived two lives and then some. Born in Germany, Wilhelm Bruns had married and fathered children in the old country. He had immigrated to Texas with wife and daughters. Widowed, he remarried and fathered five more children, my grandmother the eldest. The second wife—her name was Julia—died in 1902, when Grandma was six. In the years that followed, Opa raised two sets of siblings. He buried a son, Julius, my grandmother’s favorite brother, dead at twenty of a burst appendix.

Wilhelm Bruns was done with upheaval.

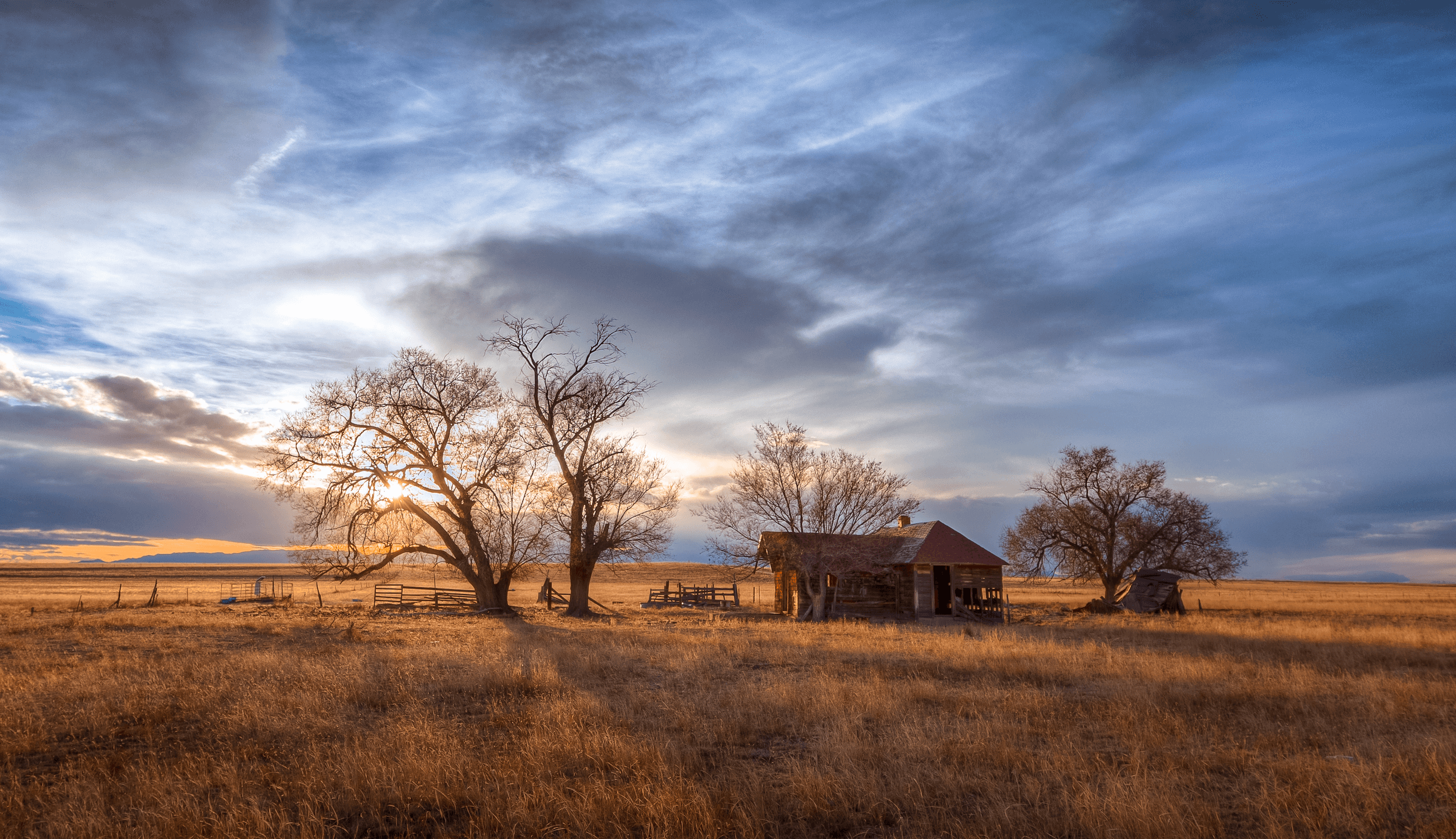

When Grandma and her family moved away from Garfield, he stayed behind. He built a tiny house for himself. A dozen years passed. Opa grew old alone. This is not to say that his kin abandoned him. His children and their families were fiercely loyal. Also wary of the old man’s insistent self-sufficiency.

I have often wondered. What did my great-grandfather think during those years? What occupied his mind? The ocean he’d crossed, the two wives he’d lost, the son? Sensory awareness, perhaps—the daily pleasures of work, eat, drink, sleep. Or the opposite—drifting, desensitized, hiding within himself from the chill of age and loneliness—a state of mind I’ve come to think of as autopilot. Did I inherit this from him—my tendency to disconnect?

Whatever his method of passing time, the years went by. And then one day on the cusp of eighty, Opa took sick. For three days, he couldn’t get out of bed. For three days, he survived on a can of cocoa and a pitcher of water beside the bed. Until Aunt ’Dele, the youngest of Opa’s offspring, came by with her husband. They took Opa to the local hospital. While he was there, his children gathered and took counsel. What to do when their father was ready to leave the hospital? They were not willing to take him back to his little house. He wasn’t strong enough; they couldn’t risk another crisis. But they knew Opa—his pride, his German hardheadedness.

And now, my favorite part of the story, revealing the ingenuity of my grandmother, my great-aunts and uncles, their love for their stubborn father. Instead of chiding and cajoling and nagging and pleading, instead of forcing Opa into intolerable dependency, into an old age home or a round of spare beds in their homes . . . though perhaps they pushed these solutions at him first. I don’t know; I never asked. But I like to think they didn’t. Besides, this is my story. My grandmother, her siblings—they are my characters, alive inside me but illusory, as were their own lives to themselves. They are twice removed from the bare facts of the story I tell here. First, by eyewitness memory, my grandmother’s memory, that gossamer veil. Second, by hearsay memory, the fragments I stitch together from what Grandma told me one afternoon more than fifty years ago. Twice a fiction, twice removed by time—narrated by Lillie Bruns Meischen years after the fact and tapped into a keyboard decades later by one David Meischen, a not-yet-born minor character in the story at hand, recasting the narrative to suit my own illusions. But hoping to trap a glimmer of truth somewhere among the words.

Part of the truth I wish to locate here is love, a love greater than self-interest, a respect greater than self-absorption.

What Grandma, Uncle Anton, Uncle Willie, and Aunt ’Dele accomplished—along with their father’s daughters from the old country—was at once simple and marvelous. They drove a flatbed truck to Opa’s place and loaded his little house. They drove the loaded truck along narrow country roads. I like to imagine field hands pausing to gape at the apparition of a house moving through the countryside, raising a wake of dust. Reaching their destination, they set Opa’s house down in his son’s backyard. Opa lived there quite contentedly—until April 30, 1953, four months past my fourth birthday.

On a bookshelf beside my writing desk, I keep framed photographs of Opa and his second wife. These pictures sat on Grandma Meischen’s dresser until her death in 1979; eventually they came to me. Julia’s photo harks back to the century before mine. A matron, clearly posed by a professional photographer, stands beside what looks to be a highboy, right elbow crooked to rest there, fingers of the left hand draped over her right wrist. The dress is formal, even severe, with a rich, dark sheen, set off by two rows of covered buttons running from neck to waist. A purse strap hangs from the gently curved fingers of her right hand, a white handkerchief artfully fanning out from the purse itself. I have only my grandmother’s word as to who this woman is. She has a name still, but little more. One death—mine is near enough—and this photograph could easily fall into a discard pile, into a box of unidentified vintage photos in a dusty junk store somewhere.

The other photo looks to be enlarged from a snapshot. Opa sits in a straight-back chair parked at the rear bumper of a car I place in the late thirties. I can hear my grandmother—or one of her brothers—haranguing him out of doors, insisting that he sit, that a record be made. The foreground is Uncle Anton and Aunt Frieda’s dirt yard, at the left edge the wall of an outbuilding. Directly behind Opa, between the building and the car, a glimpse of farmland. My great-grandfather looks like the man I remember, a composite, too, of the elderly men I knew at mid-century—black wool, white shirt, thin gray hair, face and hands that speak of hard work, hard times.

In a moment whoever holds the camera will be satisfied. Opa will rise from the chair and return to his little house. My sister and I visited him there. I sat in his lap and breathed the odors of his skin, his clothing, his bedding, his history. I carry him in me, with all my contradictions—these moments of wholeness, a little boy at home on his great-grandfather’s lap.

~ November 2018