“We died in your hills, we died in your deserts,

We died in your valleys, we died on your plains,

We died ‘neath your trees and we died in your bushes,

Both sides of the river, we died just the same.”

—Woody Guthrie, Deportee

***

“I don’t want to live forever,

But I don’t want to die tonight.”

—boygenius, Afraid of Heights

Alone, but not alone. Perched atop an exposed, wind-blown ridge in the Sonoran Desert a few miles north of the Mexican border in Arizona, the graveyard resembles a sepia tone image from the 1930s—slate gray sky, brown land. Mesquite, yucca, white thorn acacia, and cacti all struggling to survive on little rain in these rocky soils. But survive they do in this landscape of both death and life. Southern Arizona is America’s necropolis where death and dying is ever-present.

And there’s wind—groaning, growling, at times moaning. A sonorous Sonoran desert song of sorrow snaking through the arroyos and stony ravines. Here the wind is a constant, scouring the ground and bending low-lying creosote branches that act like brooms, sweeping the ground clean of all pebbles and detritus, creating angel wings on the hardpan surface. But the views from the ridge are spectacular when puffy clouds skirt the skies, migrating from west to east. In spring, after decent winter rains, things turn green, and for a brief time life seems good in the desert. But not today this January. Wailing, the wind propels a different narrative.

On Cemetery Hill, few plants have found sanctuary inside simple fencing surrounding twelve graves—a place where this sacred ground is protected from semi-wild cattle that graze and trample this landscape. The picket fence and chain-link fencing also provides a barrier of sorts to the migrating deer and javelinas, but it is largely symbolic. Not that they can’t surmount the barrier. In truth, this effort at “prevention through deterrence,” is just as ineffective as our recently expanded border Wall, but not nearly so deadly.

Slowly, we creep up the rocky road in our Humane Borders water truck, already feeling the heat of the morning sun coming in through our open windows. Even in January it can be hot in the Sonoran Desert during the day—but also freezing at night. The wind provides some relief from the heat of this warm winter day. For those of us who live here in southern Arizona, we are well aware that the desert is a place of extremes and extremists.

Today on Cemetery Hill, we decide to linger longer than usual at this family cemetery. We choose to pause on our water run at this graveyard because we are not on a schedule. We’re out here in our Humane Borders truck to resupply our water stations, and besides, the barrel is only a few hundred yards away from Cemetery Hill. We pause to pay silent tribute to this familia—a symbolic gesture we do on our monthly trek to support today’s migrants who struggle to survive.

Inside the cemetery enclosure, offerings in the form of colorful pieces of cloth, flags, rosaries, and trinkets sway in the wind, a plea to anyone passing by to visit. Diverse momentos are scattered atop the mounds of the deceased. So, we stop. We know our thoughts are no comfort to the deceased, but at least we find some solace that these people found an appropriate resting place and, for the most part, their names still endure.

The graves on Cemetery Hill are well-tended for being so far from any settlement or paved road. Several graves sprout vases filled with plastic flowers, photos, trinkets, and memorabilia celebrating the lives of the antepasados. There is no longer any trace of a building, house or even any kind of structure to know where they lived. No ranchero nor hacienda. But they were all part of a large-unified family.

The earliest birth recorded on these gravestones is 1871—Ygnacio Cañez, who died in 1963. His wife, Ysabel, lies next to him, born 1877 and died 1966. Ygnacio came up from Altar, Sonora, as a young child trailing his father and an ox-drawn wagon hauling wood, produce and other necessities for a new life north of the new border. Their hijos lie nearby—Antonio, Sofia, and Carlos. Antonio must have been a miner, his grave decorated with mining paraphernalia: a gold pan, a replica small pickaxe, and a figurine of a miner. The bisabuelos are surrounded by children and grandchildren (nietos): Manuel, Letha, Francisco, Mario, Danny and several unmarked graves in this family plot. Letha, born in 1937, is the most recent burial from 2013. The elders lived long lives—living into their nineties by looking at the dates on the gravestones. Some graves lack names, or they have been worn away by wind and time, but they are kept weed-free and in good shape. Obliterated by the passage of years but not forgotten. Not alone.

Eventually, we close the gate to the small cemetery and get back in our truck to head to our water station. Our flag is quite visible above the skyline, waving hello—a good sign that it probably hasn’t been vandalized since our last visit. In the wind, the blue flag with the international symbol of water—a spigot—flutters to our south over the sienna landscape, inviting migrants to refill their water jugs for the continuation of their journey north. Most flagpoles also have solar lights, making them more visible at night and projecting a glowing beacon of hope.

***

Sadly, a record of legacy such as the Cañez family is not typical for most migrants who perish in the vast desert beyond Cemetery Hill. Many migrants are nameless, lost, forgotten. Since 2000, nearly 1,000 human remains in the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office were unidentified and unclaimed. Their remains are buried in a potter’s field in Tucson’s Evergreen cemetery—the largest single location of unknown migrant graves in the U.S. They are Los Desconocidos, awaiting identification, a name, a family connection.

But this is only part of the story. Many more migrants who perish in the desert are never found—lost forever in a shameful land of unmarked tombs. The Sonoran Desert is an unforgiving landscape—one likened to the challenge of traversing an alien landscape—akin to “cruzar la cara de la luna” (crossing the face of the moon).

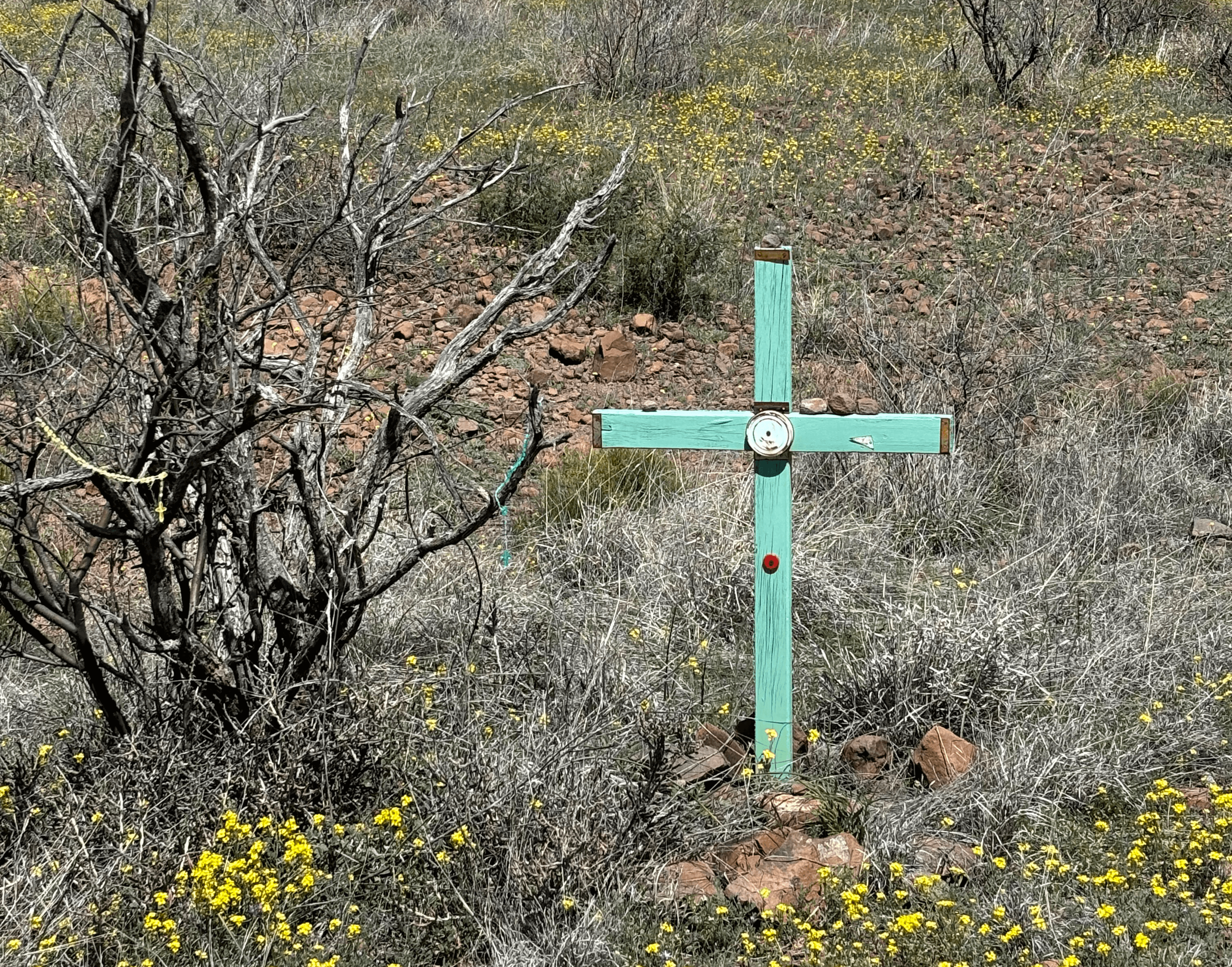

Across southern Arizona, simple crosses created by Alvaro Enciso mark the sites where the few were found. Enciso is a contemporary artist living in Tucson who explores ideas about the American dream, cultural identity, and “the other.” Through his project called “Where Dreams Die” (Donde mueren los sueños) to bring attention to those who have died in the Sonoran Desert, Enciso has erected over 1,000 crosses to mark their final stop to El Norte. Theirs, though, is a different kind of graveyard than the one at Cemetery Hill. These sites are rarely visited, hidden in the desert, only visible to a few who wander off the roads and trails. Many more migrants who die in the desert are never found. No one comes to visit their final resting places simply because they are los desaparecidos (the disappeared).

The Sonoran Desert is not a welcoming host, though it will certainly embrace you and not let go—especially if you are not prepared and alert. Death in the desert from dehydration is gruesome. So, we put out water, trying to save the lives of those forced to escape violence, drought, corruption, and persecution, hoping for a better life somewhere else. Those who die in the desert are quickly mummified by the scorching sun, turning black and brittle like tanned rawhide. Then the scavengers take over—turkey vultures, coyotes, rodents, ants, beetles. The eyes are the first to go. Then the soft tissue organs. Jason de Leon, in his gut-wrenching book, Land of Open Graves, documents that bodies begin to disappear in just a matter of days in the scorching desert. Remains are scattered as much as sixty yards from the place where the person died. Within a month, there is often barely a trace of a human at all—perhaps a few long bones like femurs and ulnae. But little else.

In comparison to the thousands of missing migrants who died in Arizona’s desert, the Cañez family on Cemetery Hill seem to be the lucky ones. Certainly, theirs was a hardscrabble existence on this desert landscape; they struggled to make ends meet through perseverance and ingenuity when there were no stores or quick stops to resupply when food ran short, or water was scarce. But they survived and thrived. And they are memorialized and respected in death here inside their modest enclosure. They created an extended family, found work, left a legacy. Not so of the many missing migrants.

How can we ignore the reality of what is happening out in the Arizona desert? How blind are we to the cruelty of our national policies that force desperate people away from established ports of entry and into some of the harshest landscapes in the Southwest? How can we sleep knowing that hundreds of people are dying each year from lack of water, exposure, hypothermia and hunger?

For the past eight years, I have been a volunteer with Humane Borders. Although I have lived in Tucson much longer, I finally reached a point where I felt I could no longer hear about the increasing migrant deaths and not do something. I was sickened about our immigration policies, tired of living under the quasi-occupation of the Border Patrol with their numerous highway checkpoints, fleets of green and white trucks speeding down our highways, and the constant helicopter flights (el mosco) buzzing through our skies chasing people—women, children, young men—seeking a better and more peaceful life. I had been donating to the Florence Project, a nonprofit that provides free legal assistance to jailed migrants, but I wanted to do more. Giving money was easy, but I wanted to do something about it. Personally, I could no longer continue living in Tucson in good conscience knowing that every day fellow human beings were perishing out in our deserts because of the lack of water.

***

Soon enough on Cemetery Hill we come to our water barrel, set on a small saddle between ravines where migrants are likely trekking on their way north to avoid detection. The barrel is intact as far as we can tell. We disembark from the truck with our bung wrench, water tester and flashlight. Each fifty-five-gallon barrel lies recumbent on a makeshift stand of cinder blocks and boards that cradle it and keep it from moving or rolling away. The upper opening is sealed with a nylon bung plug and is protected by a metal locking cap to prevent vigilantes from tampering with the water. Each locking mechanism sports a simple combination lock. Such precautions are critical to maintain high quality, clean drinking water for migrants, or anyone for that matter caught in the desert without enough water—hikers, equestrians, hunters, mountain bikers.

Usually, we find there has been water usage because the water level in the barrel is low. We test the water quality and look inside with our flashlight to see that the barrel is free from algae. From the large water tank on our truck and with the assistance of a small gasoline pump, we roll out the hose and top off each barrel and take a photo of the barrel to document the condition of the site at the time of our visit. Each barrel has stickers of the Virgin of Guadalupe as well as stickers in English and Spanish (agua potable) indicating that this is water safe for drinking. Some migrants leave behind tokens of thanks—a five-peso coin, a rosary, a hastily scribbled note held down by a rock on top of the barrel, or a prayer card.

Then it is off to the next water station for us. Rumbling along rutted rocky roads, our progress is slow, but deliberate. Humane Borders maintains a large number of water stations throughout the Arizona desert, and they are serviced by cadres of volunteers just like us. People who care about human life and suffering because no one deserves to die in the desert. But our national policies continue to force people to rely on “coyotes” to lead them across or simply try to go it alone to cross the border to make their way to the safe haven of family and friends. Sure, some make it. Others don’t. Many are never heard from again.

At pickup points or resting spots, we find baby food jars, baby food spoons, small shoes, bras, underwear, and carpet shoes—coverings large enough to fit over regular shoes and help disguise footprints in the desert sand. At some spots, we find toothpaste tubes, toothbrushes, disposable razors, backpacks, discarded phones, charger cords, shirts, camo clothes and hats, and all the other artifacts of daily living. Not trash or garbage-—these are people’s belongings.

Some who know I go out to the desert on these water runs ask: “Isn’t it dangerous with all the gun battles between cartels going on?” No. It’s not an invasion, and it’s not a war. In all my years, I have never seen even one gun battle or confrontation between cartels in Arizona. You rarely even see people—migrants don’t want to be found unless they are finally in such a desperate situation that they approach you asking for help. Sometimes, they just need food and water, and still elect to continue on with their journey.

When we do encounter migrants on our water runs, we are not allowed to transport them (it is a Federal felony), but we can provide aid—food, water, first aid, or use of a cell phone to call someone. We often ask: “¿Sabe a dónde está? (Do you know where you are?). “¿Sabe a dónde vas y dónde queda?” (Do you know your destination and where it is?). “¿Quieres que llamemos a la migra?” (Do you want us to call the Border Patrol?).

Vigilante and militia activity is always a concern when we are out on these runs, and that is why we never go alone. We always have at least two people in the truck—strength in numbers, or at least that’s what we tell ourselves. Maybe it’s a false sense of security since we are armed only with water, but we never feel truly in danger. We are sometimes harassed, shouted down, blocked on these back roads, or just followed by militia members or vigilantes. During a trip with a national film crew, a local rancher saw our truck, stopped along the road, and started taking photos of our vehicle and license plates. Then he rapidly approached, berating us for helping people from “shit hole” countries like Mexico and for luring people here with false promises. The yelling commenced. We yelled back in response. Eventually he left, using only one finger to wave goodbye.

Out in the desert, we are occasionally accosted by individuals who accuse us of aiding and abetting criminals. Our actions only encourage people to enter the country illegally, they say. “You’re no better than getaway drivers at a bank robbery.” But Humane Borders, Samaritans, No More Deaths, Border Kindness, Border Angels and other groups are simply trying to prevent deaths. No one deserves to die, unknown and thirsty, in the desert. No one.

Unfortunately, the locks on the water barrels haven’t solved all our problems with vandalism. Vigilantes like those from Veterans on Patrol, Arizona Desert Guardians, or Arizona Border Recon shoot our barrels, kick off the spigots so the water drains out, punch holes with knives or screwdrivers, or just drain the barrels until nothing is left, and then they walk away. Vigilantes have also broken the flagpoles and destroyed the flags, making it more difficult for migrants to find our water stations. At least one migrant, Nolberto Torres-Zayas, died within a hundred feet of one of our stations because, upon arrival after a long, hot trek, no water remained in the barrel because of vandalism. Nolberto, age thirty-six, was already in trouble from hyperthermia, thirst, and hunger, and died alone of exposure within feet of our empty water barrel on August 8, 2009. Enciso’s cross marks the spot—a bright yellow wooden marker in an austere and sere landscape, rosaries dangling in nearby branches.

Humane Borders maintains a “death map” which details the location of the known migrant deaths since 1990 with a red dot for each—Nolberto is just one of thousands. Ever since the implementation of the U.S. policy of “prevention through deterrence,” people have been forced away from established ports of entry to attempt dangerous desert crossings where the risks to survival are monumental. Since 1990, more than 4,100 people have died in Arizona’s deserts—and those are just the ones we know about because their remains were found and recorded by the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office. Many others are never identified, leaving loved ones back home uncertain about what happened to a family member, relative, or friend who left for “El Norte.” The “death map” serves to drive home the message that the Sonoran Desert is America’s graveyard. Since 2000, the coroner’s office in Tucson has received an average of 184 deceased migrants per year. In 2020, more than 225 bodies were found in the Tucson sector. In fiscal year 2022, a record 853 human remains were found by the Border Patrol; 43 people died in the first few months of 2023. Hundreds more will be dead by the end of summer. Looking at the death map, the Arizona desert is like a red sea, awash in an ocean of blood of red dots seemingly created by a crazed Impressionistic artist, drunk and crazed.

***

Many people think of deserts as severe, arid killing places, devoid of shade, water and humanity. Certainly, it is. Along with the Devils Highway in the Barry Goldwater Bombing Range, the Sonoran Desert here is one of the harshest environments along Arizona’s 281-mile linear border with Mexico.

The desert is blamed for so many deaths. But it is not the desert that’s to blame for these deaths—“prevention by deterrence” forces people to attempt crossing the border in remote, forbidding terrain. “The land isn’t complicit, it’s really just the people overseeing the land,” says Dulce Real, a first-generation U.S. citizen whose own family members crossed the border. Thousands of migrants die lonesome deaths in the Arizona desert, often never found. If their dying were done in the open, we would never be able to exorcise the images. But for most in the U.S., the deaths remain unknown, unspoken and anonymous. At Humane Borders, we are opposed to a border enforcement strategy based on deterrence by death.

Instead, we put out water to save lives. It’s that simple and that important. Despite what vigilantes and militia groups say, water doesn’t lure people to leave their homes and attempt a crossing of the desert, but it can save them from an agonizing dance with death. Grounded in fantasy conspiracy theories, vigilante groups accuse humanitarian groups like Humane Borders of running child sex trafficking camps at our water stations, of being pedophiles. Like Pizzagate, such fantasies can lead to disastrous consequences. The truth is far from the conspiratorial fabrications of militia groups and more compassionate than many they would be willing to admit. We are saving lives.

Migrants are not drawn to the U.S. but rather pushed and shoved to our borders by extreme social and economic conditions in their own countries. Heightened security is not the answer. When your house is on fire, you do what you can to escape as quickly as possible. No matter how many years you have lived in that house, how dear the memories, how precious the belongings, you flee. And you flee towards something safer, regardless of the obstacles. We must acknowledge that there is a conflagration going on south of our border.

Borders are myths propped up by fantasies. Boundaries are ephemeral and ever-changing. As many Hispanics in Tucson and other border communities remark: “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.” Building a wall is recreational at best, an incredible waste of resources at worst, and in general a political stunt of monumental folly. Walls don’t work to stop human movement. Ask the Chinese—despite a grandiose structure that can be seen from space, they eventually had to accept to a Mongol emperor in the end.

Pushing people away from established border crossings and ports of entry, our national policy has been to try to discourage illegal crossing by forcing them to reconsider attempting crossing through remote, harsh desert areas where death is a distinct possibility. We think deadly conditions will deter people from coming who have already faced the potential of death, torture, persecution, or famine back home. It hasn’t worked for years. Recent research has shown that the number of unauthorized crossings has increased with increased enforcement and militarization of the border.

So, we continue to haul water out to stations throughout southern Arizona, hoping we can save lives and prevent the needless suffering for people looking for a better life. While we drive through the desert in the relative luxury of our four-wheel drive truck, complete with air conditioning and a radio, we really don’t understand what migrants are going through by trekking through the desert. How, then, can we expect the larger American public to understand? It is unreal to them, and even if it is real to us, we still can’t fully fathom the hardships, hazards, and tribulations of “crossing.” We can read about it but still not comprehend women bringing roller bags and wearing high heels for their trip north who are told by unscrupulous “coyotes” that they will only have to walk a short distance to an airport where they will be flown to see their loved ones. They are often abandoned, raped, or robbed and then left to fend for themselves. In truth, finding water is just a small yet important part of the struggle to survive.

Southern Arizona is a large necropolis populated with crosses to individuals who believed they were only passing through. But unlike the family members interred at Cemetery Hill, Enciso’s crosses don’t mark graves of people who rest peacefully after long, fulfilling lives. Rather, his crosses mark the final destination of tormented, restless souls whose lives were cut short by our national immigration policies, victims to our support of corrupt governments in their home countries, and from climate change accelerated by the continued use of fossil fuels to prop up our modern standard of living. We are all complicit because these policies are carried out in our names.

We defend our continued use of fossil fuels but resort to racism to justify why we need to keep climate refugees away—“the others” will overwhelm us if we are not vigilant. As Tom Buchanan quipped in The Great Gatsby, “It’s up to us, who are the dominant race, to watch out or these other races will have control over things.”

At the top of Cemetery Hill, I stand and look out over the vast, undulating horizon, rocks carpeted in green and yellow lichens shimmer in the intense light. Today, no one else is in sight. But there are probably migrants out there—hiding in lay-up, waiting. We are alone, yet not alone.

Hill after hill rises to the south toward the border, carpeted with wheat-colored grasses waving in the wind. A false gesture of welcome. It is eerily silent, save for the wind. But if you listen closely enough, you can hear the wail and moan of lost souls. Fantasmas still looking for a home, for peace, for tranquility, for a life beyond persecution, violence, and abuse. Restless souls, wandering the earth, searching, looking for their families and a final resting place with dignity. Sometimes you can almost hear a scream.

Walls will not stop this searching. Nothing will until we change our policies. Until then, the wailing will only continue. Alone but not alone.