Short Story

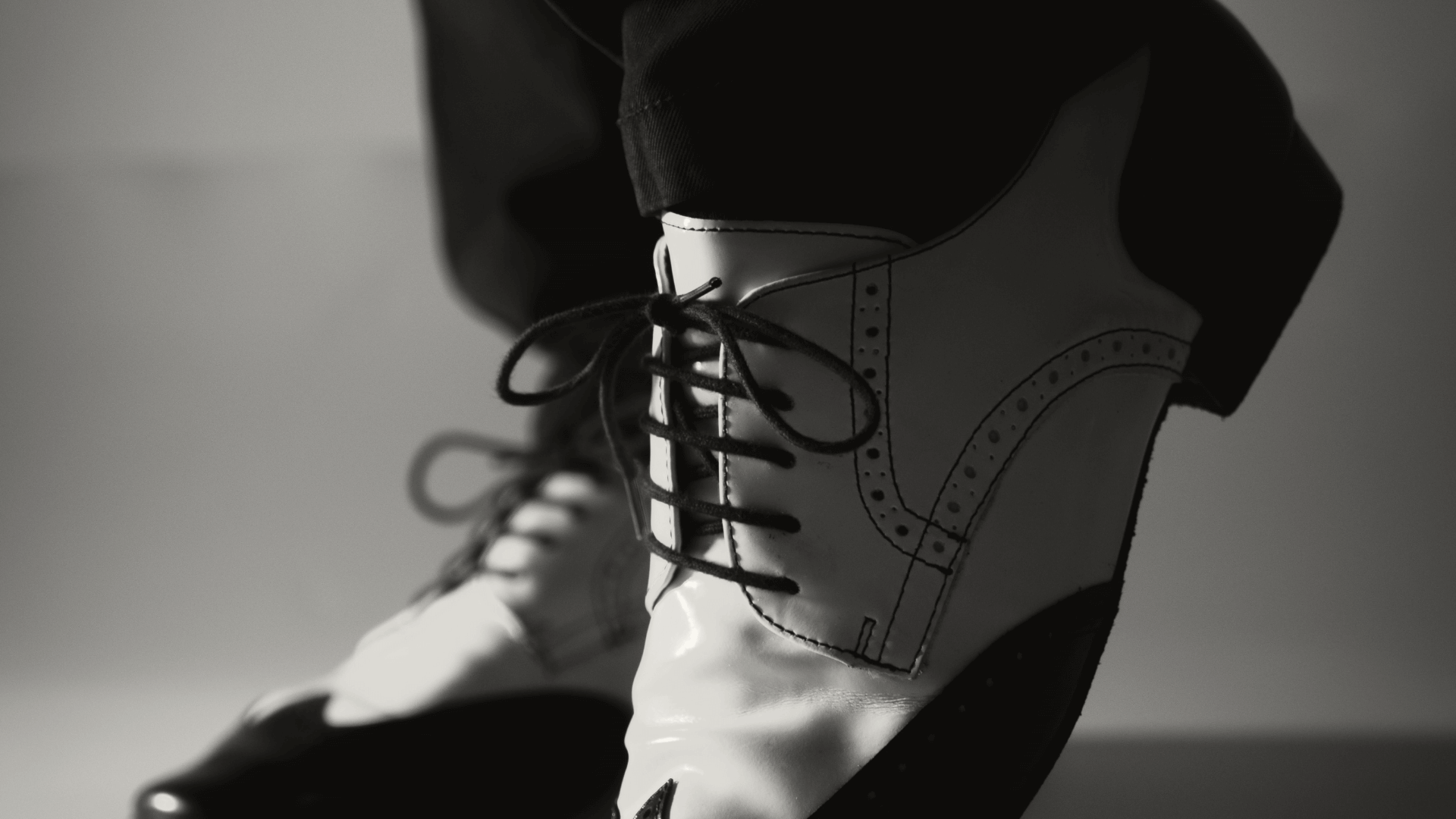

The bright, green grass was covered in early morning dew drops. They slide down its blades and leave wet spots on my pumps. Rocking my weight on to the heel, and then back to my toes, I focus on how each shift digs the shoes further into the soft ground. I wish I could just take them off, stand even, and feel the earth with my toes. But even then, I would still have to deal with my stocking’s itchy webbing. If I knew how uncomfortable I’d be, I would have argued more when I saw this outfit laid out for me. I really couldn’t care less about looking the part and... God, why can’t I find enough air out here? It’s almost as if my lungs are leaking air through a tiny hole.

Looking up at a sudden pressure in my palm, I meet Mom’s worried eyes. Looks like she hasn’t been sleeping either. Was this her way of checking on me? Or trying to tell me to pay attention and to listen to the stranger’s voice magnified by speakers? She holds my gaze a moment, then giving my hand a second squeeze, she just turns back to face the front. In the new light, I can see wet lines tracing her cheeks, and she really does look so tired. My palm stays firmly in her grasp; I don’t remember the last time we held hands.

Punctured lungs shrinking again, I quickly close my eyes.

Inhale. Exhale.

The branches above shift and bend with the wind. Keeping the sunshine and shadows restless against the people and chairs under the cover of its leaves. The figures surrounding us stay stiff against the breeze. Their clothes flap from them like flags tied to a pole. They remind me of stiff, weak, dead trees.

Inhale. Exhale.

My third-grade teacher once told me that in times of intense stress, or when the imaginary little fat man uses your chest as a drum, that listing objects around you can help calm you down. Problem is, there’s nothing boring or plain to list at your best friend’s funeral.

“-and now, a few words from Mark’s good friend, Dayna.”

Hearing my name snaps my attention to the flower covered podium. No longer able to balance, Mom and Dad dip to support me. The speaker is holding out his arm, gesturing to me. As if he’s the host and I just won the award. Ankles wobbling in my heels takes all I have to stay upright. Mom’s hands around my waist lead my body down the aisle, Dad’s forearm guides me up wooden steps. A mic gets adjusted in front of my face. Forcing myself to pull out the prepared speech stuffed in my pocket, I notice my palms are wet. Focusing hard, I start to make out my own writing. Somehow, without vomiting, I read from it out loud.

“Mark Perdita is held close to the hearts of the many people he had an impact on in his too short... lifetime.” The last word snatches up my breath and the hoarse voice stops.

These words are wrong. It feels like I’m speaking a language my tongue just can’t learn. The letters written by me don’t sound like me, or Mark. All that’s left of lifetimes are inadequate, thin, pieces of paper. Lined with sentences that ring with the same groan of defeat that is heard through every eulogy, at every funeral. Looking up in embarrassment, no one seems to mind my pause. The crowd of black stays unmoving, except Mark’s Aunt Reus, who, with her head down, is nervously pushing her cuticles back with a copper penny. I know it’s her from her recognizable church hat, the one that gets mocked in whispers in-between sermons. The ugly thing is an easier sight than the rows of stares from the other’s blank faces, almost melting off with sympathy. They don’t get it. They won’t get it. They get to simply whisper ‘too young’, click their tongues, and move on. The only person who knew Mark was me, and the only person to understand anything, was Mark. My prepped eulogy, a tangle of ink, might as well be sheet music. I shove it back into my peacoat. Tears are falling again; I don’t know what to do. The audience stays silent, as if one free sob would shatter them all.

Mark and I used to hold our breaths like that whenever we passed a graveyard. Believing that, ghosts hiding behind the tombstones would mistake us as one of them and leave us alone. Whenever Mark couldn’t last and gasped for breath, I would jump at him, pretending to be a ghost finding him out. The game faded as we grew up, but just a few weeks ago when passing a cemetery, I watched Mark’s chest freeze. I don’t think he even noticed he had done it.

“Mark was the biggest part of my life.

You know when you sit beside someone you love, and as you listen to them speak, you put your head on their shoulder? Have you noticed how perfectly it all fits? The heavy head, nestled by the neck, under the jaw. Every moment with him fit, just like that. He was so bright that with him gone, everything is darker. He made me laugh, made me brave, and showed me he cared when he really didn’t have to. When I didn’t deserve it.

Once, on our way home from John Mayfield’s end of the school year party, Mark had missed his curfew. Even as he was panicking about it, the speedometer never read higher than the speed limit. Cause that was Mark.”

His small, red Toyota made it easier to maneuver out of the packed driveway. It helped even more that Mark was a pretty good driver, even after having failed his test twice before finally passing. I was happy that backing out didn’t add to the stress of the situation, but all the adjustments made my drunk head roll and the liquor in my stomach swirl. It was deafening quiet on the road after the music blasting from inside the house. Even though we were going straight down the highway at that point, Mark stayed hunched over the wheel, jaw locked. “They are so, actually, going to kill me this time. I am so screwed,” he had said neither to me, nor himself really.

“We had left John’s house half an hour after he was supposed to already be home. I kept avoiding leaving, and I think the effort it took to get me in the car took a toll on poor Mark’s life.” Giggling to myself, I wasn’t talking to the flock of mourners anymore, I was with Mark again. “I bugged him to drive faster. I tried to make it lighthearted, get him to laugh a bit, but it came out as more of a plea. The threat of hurling was too present. Mark just sighed, and our speed didn’t change. He’s such a wimp, you know?”

A chill on my toes started to grow, and it was all I could focus on. The ice spreading from my feet to my ankles become so uncomfortable that I frantically repositioned myself to cover them. The fear of vomit was a far memory now; I needed to get Mark’s help before my feet fell off.

“Mark! I need you to turn up the heat, I’m freezing!”

He stayed focused on the pavement.

“Please! My toes are turning blue, next they’ll be black, and I’ll lose them to frostbite!”

Mark finally looked at me. I hoped he’d be as concerned as I was about the hypothermia setting in as I rubbed my feet tucked under my thighs.

“You have no shoes. Where are your shoes?” he asked.

What a stupid question to ask; shoes were not nearly warm enough to ease my pain.

“I don’t know!” I replied impatiently.

“Your shoes are not in this car,” Mark noted while quickly surveying the back of the car and the floor of my seat.

“I guess.” I could no longer worry about silly things; my feet had now turned my hamstrings cold. I was trying to find a new pouch of warmth for them.

Suddenly, Mark was turning the car around. “Your shoes are back at the party.” I groaned at the shift; puke burned up my throat. That had Mark finally laughing.

Back at John’s, I wasn’t allowed to leave the car while he went in. Claimed he didn’t want to give me the chance to lose my shirt too. He had turned up the heat to thaw my toes, so I let him get away with that. Later, he came back with the heels, except now, the blue satin had something brown on them.

“I was surprised when he turned around for a pair of shoes that he noticed I was missing. When I thanked him, confused, he responded with the fact that it took me four months to save up for them. I didn’t even know he knew that.”

Tracing the wood of the podium, I can smell the air fresheners in his car again.

“He didn’t get home until an hour and a half past when he was told to be. Got grounded for a week, and even I couldn’t see him.”

His parents are sitting in the front row, their arms intertwined. Should I have said that?

“It’s hard to describe him, because he’s so perfect that any words used fall flat. ‘Mark Perdita was a star baseball player, got good grades and had many friends.’ But Mark... Mark was learning to tap dance!” Chest contracting, was I laughing or sobbing?

“For a while, I was getting wakened by the sound of metal hitting my basement floor. The sound would echo all the way up to my room, and there was no ignoring it. So, I’d drag a blanket with me, and meet it head on.”

It was dark, and the unfinished steps downstairs were cold against my feet. I really hate cold feet but can never seem to find my slippers. The closer I got to the soon-to-be-a-theatre room, the warmer the air got. Opening the door, I got hit with a wave of heat and blinding lights.

“Did I wake you?” he said sweetly, flashing me a smile. Even at two in the morning, I couldn’t help but smile back. “Mark, I thought you got over this tap thing?”

“Nope,” he replied in between breaths, “no way. Especially when I get the pleasure of waking you up at midnight.”

“Mark was in front of our big TV again, wearing his baseball hoodie, shorts, and black leather tap shoes. Sweat was seeping from his pores as he followed online tutorials. My mom had laid out cardboard for him to practice on. We weren’t usually so welcoming of Mark’s phases, but we knew if he did this at his own place, his brothers would beat him senseless.” A chuckle arose from somewhere in the audience.

“I also really liked watching him, he sucked at it so much. I never did understand why someone so good at everything enjoys the one thing he sucks at.”

“Look Day!” He turned away from the video to me. “It’s called a paradiddle.”

I watched him do some sloppy stomping, then pose for applause.

“Cool, hey?” He went right back to his video, proud enough of himself to not wait for my praise. I made some comments about how similar he looked to a temperamental toddler.

“Why are you so obsessed with this?” I asked.

He stopped for a second. “It’s the only thing my parents can’t turn into some elaborate career path” was his response.

Nets of pain spread over my head; I close my eyes at the ache. I try to focus on my breathing as my lungs feel flat, as if completely drained of any oxygen. I taste rust, can teeth throb? I try to look to Mark’s family, realizing what they didn’t know about his dancing. His tap shoes are still tucked in our coat closet. His parents just look to his brothers, his brothers continue looking at me. Their faces are wet; I’ve never seen Ashton and Bryan cry before. I should feel for them, but I can’t care about their feelings too, right now. Selfish, but true. My heart already aches too much.

He was everything. He’s gone.

“I never told my best friend I loved him. That for all those years of him living down the street, walking to school side by side, and spending weekends together, I never told him how I wanted to spend the rest of my life near him. Not like this, forever stuck in this chapter of life,” his box looks so small, “but with him looming over me, whispering his jokes in my ear.” I swallow blood trying to push down sobs. “I never told him I wanted to wake up every morning to his beautiful light brown eyes and to fall asleep every night with his weirdly warm hand in mine.”

I look up to the sky, like he used to when he was thinking hard.

“I love you.”