The Gilded Cage

The Transit of Venus

A terrible crime was committed to-day. This may come as no surprise to the modern reader, inundated with tales of the most devious schemes, flagrant improprieties, and spectacular acts of violence, but this crime was unlike any other. For the suspects shall not appear before any court; instead, the accused sit upon the bench, the nation’s highest. While the crime was not in and of itself sanguinary, it was borne of, witness to, and surely portending more suffering and bloodshed. The proximate victim of the crime was not a person, but a solemn promise put into these few clauses shortly after the late war. Perhaps they died long ago, but their demise became indisputably apparent to-day.

Before these events pass into the haze of memory, I must hazard an account of the murder of these words and their promise. In so doing, I beg certain indulgences of the reader. I have relied upon the law books, the newspapers, and the personal correspondence of these gentlemen and ladies to tell this story in a way that might pique the interest, which has required some dramatic liberties. For those demanding readers who insist upon seeing every internal strand in the net of my speculation, an account is available at no cost. For the reader who is content with my methods, we turn to the tale of how our noble Reconstruction came to an end.

The Justices’ conference room, ordinarily the witness to judicial sparring, now became the battlefield for a newspaper war. Justice Stephen Field led the first charge, greeting his colleagues the day after the election with The New-York Sun, whose bold headline declared “TILDEN IS ELECTED. THE DEMOCRATS JUBILANT.” On top of that, he cast The New-York Times, which pronounced the election “DOUBTFUL,” and The New-York Tribune, which reported “TILDEN ELECTED.” But the following day Justice Samuel Miller, appalled by the dueling newspapers but always prepared to needle Field in good sport, obtained his own copies of the Tribune, which on Thursday opined “HAYES POSSIBLY ELECTED,” then on Saturday suggested “THE ELECTION OF HAYES ALMOST ASSURED.” Field replied with a late edition of The Sun on Friday, which reported that “HAYES CONCEDES TILDEN’S ELECTION,” which came as a surprise to every man who read it and was promptly dismissed.

“We have a considerable number of cases to discuss, my Brothers.” Chief Justice Morrison Waite had sought several times to begin the Saturday conference but was persistently ignored. His eight brethren gathered about the table consulting the newspapers, reciting the conflicting accounts to one another.

“The recount in Louisiana is expected to favor Hayes, according to the Chief’s old friend,” Justice Noah Swayne read, brandishing a journal from that state.

“Evarts cannot be trusted upon such matters,” Field objected.

Waite bit his tongue. The Friday after the election, President Grant had commenced efforts to dispel the uncertainty by dispatching certain Republicans to New Orleans to observe the recount. Twenty-five Republicans heeded the call, among them William Evarts, Representative James Garfield, and Hayes’s man Stanley Matthews. According to a telegram from Evarts, these visiting statesmen had persuaded the canvassing board members in Louisiana, themselves all Republicans, that the majority for Tilden was more properly understood to be a majority for Hayes.

“The same is expected in Florida,” said Miller, shaking his head. “The papers may have reported at first that Tilden won the state, but there are now claims that ballots were Ku Kluxed — either disappeared or destroyed entirely. An outrage!”

“Pah!” Justice Nathan Clifford did not believe the newspapers, preferring to leave the purity of his convictions unmolested by hostile information. “If the Negro cannot cast a paper ballot properly, those ballots might well be tossed aside. That does not mean that any ballots were destroyed.”

“Brother Clifford,” Miller said, “that is not the end of the matter. Here we read that in some places, Republican symbols were printed upon ballots for Democratic candidates, so that some voters were deceived, through the design of the ballot, into voting for a candidate for whom they did not intend to vote!”

“It is not the fault of the Democratic Party that so many Negroes remain illiterate,” Clifford scoffed. “In any event, there is a plain answer as to who ought to win the election. The election in South Carolina was conducted under martial law, and the results for Hayes should be dismissed entirely, which leaves Tilden with the majority!”

This outlandish proposal drew the ire of several of his colleagues.

“The State of South Carolina was properly readmitted to the Union two presidential elections ago,” Justice David Davis said. “You cannot kick it out again now because you dislike the result!”

“My Brothers,” said Waite, “I must ask you to cease discussion of this matter.”

“This dispute may be promptly resolved,” said Field, perceiving Waite’s impatience as the perfect occasion to silence the claims of his Republican colleagues. “Judge Deady reliably informs me that one of the Republican electors in Oregon, old Windbag Watts, is a postmaster. The Constitution is plain that no elector may hold public office, and thus Watts must be disqualified. The Oregon Constitution is equally clear that the Governor must appoint a replacement, and he shall appoint a Democrat. That one electoral vote is sufficient for Tilden to prevail.”

“I would be surprised to hear that Oregon went for Tilden,” said Miller.

“Oh, the state is solidly for Hayes,” Field allowed. “But the Democratic Governor could appoint a Democratic elector and end the matter. Then we would not need to explore the extent of Republican thievery in the Southern states.”

“Brother Justices,” Waite began.

“Republican thievery!” Swayne exclaimed. “Why, it was the Democrats who kept Negroes from the polls!”

“Brother Justices,” Waite continued, “I have every confidence that the Constitution will — ”

“Brother Waite,” Miller interrupted, “the Constitution is of little aid to us here. The relevant provision states that ‘the President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and the House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.’ Counted — but by whom?”

“Why, it is clear that the President of the Senate shall count the votes,” said Swayne.

“Of course you would say that,” said Field. “The President of the Senate is a Republican Senator, and he will undoubtedly count all of the disputed votes for Hayes.”

“In the view of the Founders, this was all a self-evident matter of mathematics,” opined Justice Joseph Bradley.

“It is self-evident,” said Field. “If there is an inability to count, then the Constitution plainly states that the House of Representatives should elect the President and the Senate elect the Vice President.”

“That will result in the Democratic House electing Tilden as President, and the Republican Senate electing Wheeler as Vice-President!” objected Swayne. “We will have divided government!”

“Far better to follow the Constitution than to countenance the frauds of the Hayes campaign,” said Field.

“This whole affair is an outrage!” said Clifford. “Tilden won the popular vote; indeed, he has won something like a quarter million votes more than that charlatan Hayes.”

“There were some in the Senate who anticipated this very conundrum,” ventured Justice Ward Hunt, “my good friend Senator Conkling among them. Yet no action was taken.”

“A small delay shall do no harm,” Justice William Strong sought to assure his colleagues, “as the result of the election will no doubt become evident.”

In such troubled times, Roscoe Conkling found satisfaction in retreating to the gymnasium, stripping to the waist, and pummeling a punching-bag with the volley of blows that he might otherwise have rained upon his antagonists. Now he paused, gasping for air, his vast chest heaving.

No resolution was imminent. Conkling had vanished from public life for the majority of the campaign, pleading poor health and emerging only once in Utica to speak upon Hayes’s behalf. Yet the question could no longer be avoided. The members of the House and Senate had returned to Washington in early December; two days later, the electors of the thirty-eight states met in their capitals and performed their solemn duties, filing a certificate for either Tilden or Hayes. The electors of Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina, however, filed certificates for both Hayes and Tilden. Conkling had rolled his eyes when the certificates were offered and accepted by the Senate, there being no public controversy that lay outside the capacity of Congress to complicate. Both candidates had won? he thought. What d—d nonsense!

Conkling wiped the sweat from his brow, assumed the pugilistic stance, and commenced another round of fisticuffs. He struck a firm uppercut. That the President had previously called upon Conkling to offer him the post of Chief Justice, and been rebuffed, had not dissuaded Grant from requesting that Conkling put an end to the confusion.

Conkling knew he was not an illogical choice — with one punch he was a Republican like Hayes, but on the next strike, he was a New Yorker like Tilden. On the third punch, Hayes was not his candidate of choice, and Hayes’s nomination had come at some embarrassment to Conkling. Upon yet another blow, there were particular delicacies in placing Conkling in this position, chief among them that Conkling believed that Tilden had in fact won the election, although he had the good sense to keep this impression to himself. But Grant had acquiesced in the distribution of so much patronage to Conkling’s benefit that it would have been impossible to refuse.

Right, now left, now right, and right again. Grant ought to have run for a third term, he thought, and this foolishness would have been avoided. Left, now right, and left and left. He paused for a breath, and to think of Paris, for she had loved Paris.

He whirled away from the punching bag in agitation. Having had the woeful responsibility of deciding the national election thrust upon him, there was only one logical course available to him — namely, to assign it to somebody else. Perhaps a small number of men might shoulder the burden, with five men from the House, and five men from the Senate, of which five men would be Republicans and five men would be Democrats. The House Judiciary Committee had reported favorably on the notion of a special committee to decide the winner, and the Senate did the same. But there was no agreement.

Now what? Conkling thought. He strode to the stonewall of the gymnasium and nearly lunged at it in frustration but knew better than to bloody his hand. He contemplated the futility of a commission evenly divided of Senators and Congressmen, and Republicans and Democrats — there would be five for Hayes and five for Tilden. But what of the Supreme Court? Here Conkling felt the acuity of thought that only intense physical exertion confers. What if five Justices of the Supreme Court were named to the same electoral commission, with the total number of commissioners being fifteen?

Conkling mulled the prospect with care. To be sure, the legislation creating the commission would have to guarantee that Clifford and Field would serve on the commission, as they were the only two Democrats on the Court. Meanwhile, Waite and Swayne would be disqualified as Ohioans personally friendly to Hayes, and Strong feared God so much more than man that he would be beyond persuasion. Yet the other Republicans all presented interesting targets: Davis fancied himself above partisanship, Miller could be persuaded by the proper argument, Bradley was an odd enough duck to vote against the party that put him in office, and Hunt could always be leaned upon if circumstances required. And in any event, Conkling’s sycophants from the Customs-House had amassed enough gossip to blackmail Tilden for three presidential terms. There was no shortage of men who might be bent to his will, once he resolved where his best interests lay.

Conkling tore off his boxing gloves, for there was no time to be lost.

But the bill that went to Grant left one detail unresolved. The bill designated the participation of Justices on the commission by circuit — the First, the Third, the Eighth, and the Ninth Circuits, empaneling Justices Clifford, Strong, Miller, and Field, respectively. There was little doubt as to how each Justice was likely to vote — Field in particular — and with five Republicans and five Democrats from Congress on the Commission as well, it was inevitable that the Commission would be seven on the one side and seven on the other. The bill required the four Justices to choose a fifth, the fifteenth member of the Commission and thus the man who would in all likelihood decide who would become President.

Fortunately for the four Justices gathered in conference, the decision was as evident as it was momentous.

“I propose our Brother Davis as the fifth member,” said Clifford. “He is known to be fair to Republican and Democrat alike.”

“I concur,” said Miller. “In my many years with the man, I have seen him courted by the Republican Party as well as the Democratic Party. There can be no question that he shall be acceptable to everyone.”

“Although I dispute the necessity of this Commission,” said Field, “in that it seems evident to me that Tilden prevailed in the election, I have more faith in Brother Davis’s sense of fairness than anyone else’s.”

That left Strong. “I have prayed deeply upon the matter. It has been the general expectation of the nation that Brother Davis shall be the fifth Justice, and the fifteenth man on the Commission. In my heart, I know that decision to be the godly one.”

“As we are in agreement,” said Clifford, “I shall send a messenger to ask him to come to conference, where we might formally propose the position to him.”

“There is no need,” Miller said. “I have taken the liberty of asking him to arrive here, some fifteen minutes after the time we agreed to gather.”

“That seems rather a breach of protocol,” Clifford frowned, “but given that the Commission must begin its work at once, I suppose it can be overlooked.”

Within minutes, Davis was escorted into the room, a vast overcoat protecting his bulk from the late winter chill.

“Brother Davis!” Clifford exclaimed. “Please have a seat.”

“I would rather not,” said Davis. “I expect I shall not be here long.”

“Fair enough,” said Clifford. “Brother Davis, pursuant to the authority granted to the four of us under the bill establishing the Electoral Commission, we have unanimously decided that you would serve as the fifth Justice, and the fifteenth member of the Electoral Commission. We congratulate you, but remind you that we must begin work as soon as possible, on Monday.”

Davis was still for a moment.

“Brother Clifford,” he said. “Brother Miller, Brother Field, and Brother Strong. I must regret to inform you that I cannot accept this honor.”

There was silence for several moments.

“Did you say ....” Miller began.

“What!” Clifford cried. “Sir, our question to you is whether you will accept this offer.”

“I am afraid not,” said Davis.

“President Grant’s term ends in little more than a month,” said Clifford. “We cannot afford to wait even one more day.”

Davis smiled, but without his usual good humor.

“I am afraid that is it not a question of when. I am unable to serve, not at all.”

The four other Justices fell back in astonishment.

“Good heavens, man!” Clifford sputtered. “What impediment is there to prevent you from serving your country?”

“I intend to continue to serve my country, Brother Clifford,” said Davis stiffly. “And the people of the State of Illinois. I have received a telegram this morning advising that the legislature of my state has elected me Senator.”

“Senator?” Miller cried. “But you are a member of this Court!”

“That is true,” said Davis. “And I regret to inform you that I must resign from it.”

Field burst out laughing. “I knew this day would come! But I did not anticipate that you would arrange your affairs so cleverly!”

“When did this happen?” asked Miller, still astounded.

“It appears,” said Davis, “that the state legislature has been voting for two weeks on a Senator but was unable to reach agreement. Very late in the deliberation my name was put forth as a compromise candidate, and I was, unexpectedly, elected. I must now give up my seat on this Court, and thus the Commission.”

“When will you be leaving us?” Clifford asked icily.

“I must be sworn in by the fourth of March.”

“The fourth of March,” Miller repeated. “Now surely you understand that your election complicates matters for us. Not only must we find another colleague to serve upon the commission, but now your seat will be a prize for the winner — we are deciding not only upon our next President, but our next colleague.”

“Perhaps that means we should all be disqualified as having an interest in the matter?” Strong ventured.

Davis said nothing.

“Brother Davis,” Clifford said sternly, “it appears to me that your election to the Senate makes you all the more eminently fit for the position, as a member of two branches of our government.”

“I must disagree,” said Davis. “Instead, it seems to me that by serving, I would give the Senate six votes on the commission, and this Court shall only have four votes. That is contrary to the spirit of the enterprise.”

“You are a member of this Court, and you must act as one!”

“I did not agree to be a member of this Court for the rest of my life.”

“I shall proudly die in harness!” declaimed Clifford. “But it appears you have made other plans.”

“The people of my state had other plans.”

“The people of this nation require your services!”

“When I accepted my place upon this Court,” Davis said quietly, “I did so as a favor to a friend, a friend who is now long gone. The people of his state are now offering me an honor that they denied to him. I shall not decline it.”

“Sir,” Clifford replied curtly, “I must conclude that you arranged for your own election to evade the responsibility that the rest of us have not hesitated to bear. You have been placed in the crucible and found wanting. I shall not regret your departure.”

“Now, now,” said Miller, who had cast his mind over his conversations with Davis over the past year, wondering what he might have missed. “Brother Davis, I am sure I speak for the entire Court when I express my pleasure in serving with you.”

Davis nodded. “Thank you, Brother Miller. As you all must know, it has been a great honor to serve with you all. But I have long contemplated a return to political life.”

“I believe we must ask you now to leave us,” Clifford grumbled, “as we must now settle upon a fifth man expeditiously.”

“I do not see how hard that will be,” said Field. “The number of eligible candidates is diminishing so rapidly.”

Davis excused himself, leaving four glum men.

“We are left now with only four choices — the Chief, Swayne, Bradley, or Hunt,” said Miller.

“All Republicans,” said Clifford. “It hardly matters now which one you select.”

“I disagree,” said Field. “The creation of the Electoral Commission owes itself to the work of Senator Conkling. I propose that our Brother Hunt serve as the fifth justice; he is close to Conkling, and it would be a fitting tribute to the Senator’s labors.”

“That seems most agreeable,” said Clifford. “Shall we vote?”

“Hold!” Miller exclaimed. “Brother Hunt is from New York and might be suspected as harboring some prejudices concerning Tilden. If we are to consider a man from New York, we might as well consider a man from Ohio, either Brother Waite or Brother Swayne.”

“Hunt and Conkling are both from New York, to be sure,” said Field, “ but I am not aware of any personal relationship between Hunt and Tilden. But it is well known that Waite and Swayne are friends of Hayes.”

“Our Brother Bradley is not from either New York or Ohio,” Strong interjected, “and so cannot be accused of any such prejudices.”

“Bradley would not be objectionable,” said Field.

“I do not mean to impugn the intellect of the man,” said Clifford, “for it is beyond dispute. But he is entirely a Republican.”

“He is not incapable of reason,” Field turned to Clifford.

“Why not the Chief?” said Miller.

Field turned to Miller and looked him coolly in the eye.

“Are you willing to compare Brother Bradley’s intellect to Brother Waite’s?”

“I suppose not,” Miller muttered, for while the workings of Bradley’s mind seemed mysterious and incomprehensible, there was no disputing that he was a genius. Yet Field’s advocacy on Bradley’s behalf was unexpected, as the two colleagues had never been close.

“It seems to me,” Field continued, “that both Brother Strong and I are in favor of Brother Bradley for the fifth position. Unless Brother Clifford and Brother Miller unite behind one candidate, I propose we vote on the matter.”

The four Justices grimly voted for Bradley, having no better choice.

A few days later the man of the hour stood, only inches from freezing rain, patches of ice forming upon his red beard. Senator Conkling had remained outside in the vestibule for several unexplained minutes, on the excuse that he was waiting on a late arrival. Spurning the requests of his hostess, who begged him to come inside to her soirée lest he catch his death of cold, the Senator only advised sternly that he was obliged to wait. The news of the Senator’s vigil spread quickly through the reception, and the partygoers wondered whether they would already be seated for dinner by the time the Senator finally made his entrance.

More pressing, of course, was the question for whom the Senator could possibly be waiting. After extensive consultation, the most persuasive explanation was that Governor Hayes would be making an appearance that evening, and that Conkling, as a leading man of the Republican Party, was obliged to escort him to his first, albeit unofficial, reception in Washington. This prospect made the hostess swell and nearly burst with pride. To this speculation, however, came the rejoinder that Conkling was not personally friendly to Hayes and, even more persuasive, had carried a bouquet of flowers under his arm, which would seem an odd gift for the Governor. The speculation had continued to the point where it was suggested that the flowers might be for Lucy Hayes when the sound of the door slamming interrupted the gathering.

Into the parlor strode Senator Conkling, with a beautiful woman on his arm. It was not Lucy Hayes, and the Governor was nowhere to be seen. This woman carried herself with profound sensuality and confidence. She looked entirely familiar and yet utterly changed. Her petite frame, the small, upturned nose, the light in her eyes, created a sudden shock and sensation among the best members of Washington society, who did not at first believe what they saw. Even the finer ladies dropped their jaws open in vulgar disbelief while the gentlemen nudged one another in recognition of the woman on Conkling’s arm.

Kate Chase Sprague had returned from Paris.

It was perhaps inevitable that the Electoral Commission would become the subject of Fieldish connivance. Alone among the Justices, Field was pleased to be called to the Commission, which would render an initial determination as to whether the electors in the four disputed states — Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina — would be awarded to Tilden or Hayes. But additional security was needed in the event that Field could not persuade the members of the Commission to rule in Tilden’s favor, because the determination of the Commission could be overruled only if both houses of Congress agreed, and Tilden had few certain allies in Congress. Fortunately, the Fields were nothing if not resourceful.

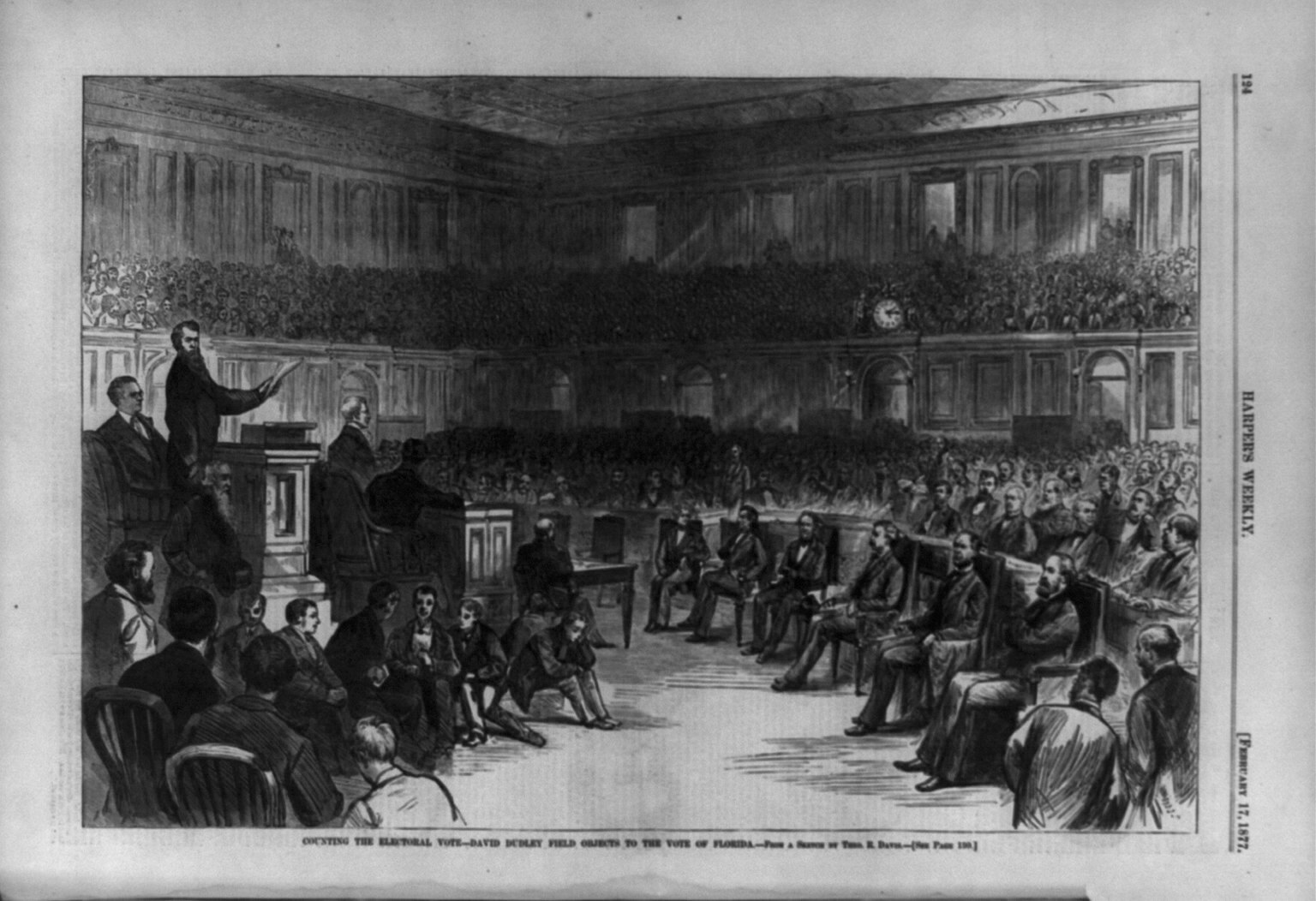

“I cannot believe that your brother has any interest in being a Congressman.” Miller squeezed his bulk into one of the fifteen narrow wooden chairs set around a grand table in the well of the Supreme Court. It was nearly three months after the election, but there was still no President-elect. The work of the Court had been effectively suspended, and counsel tables pushed off to the walls, to permit the installation of the Electoral Commission in the Supreme Court’s chamber. The Justices sat with their backs to the bench, with the Senators and Representatives along the other three sides, which left the larger men with insubstantial room to maneuver. From the Senate came Edmunds, Morton, Frelinghuysen, Thurman, and Bayard; from the House came Garfield, Payne, Hunton, Abbott, and Hoar — five Republicans and five Democrats. The spirit of the gathering, though amicable, was not tranquil, as the determination of the Commission would almost certainly decide the Presidency.

“David believes in public service,” Field said. He nodded at his brother, who was now standing at a makeshift podium in front of the cushioned sofas that, for the time being, would host the counsel before the Commission. On one side, David Dudley Field and old Jeremiah Black represented the Democrat Tilden. On the other, Evarts and Matthews represented the Republican Hayes. The members of the Commission perceived some amusement in observing the tall, broad, and driving Field brother standing next to the lean, angular, and droll Evarts.

“It seems rather that he believes in doing anything to advance the interests of the Democratic Party,” Miller replied.

“There is nothing untoward about it,” Field replied. “A congressman from New York resigned to become Mayor of New York City, so there was an empty seat in the House. Ought the people of New York go without representation? And should Tilden have ignored his responsibility as Governor to appoint somebody to that seat temporarily?”

“But David is in Congress at the same time he is representing Tilden before this Commission. He has his finger in two pies at once!”

“I have never understood that metaphor.” Field wiped his spectacles clean and thrust his nose in the air. “There is nothing wrong with more pie.”

Miller grunted, for there was no persuading Field. The two Justices, as judicial representatives of the Commission, had attended a joint session of the Congress as the electoral votes were counted, beginning with the electoral votes of Alabama being awarded to Tilden. When the joint session arrived at the electoral certificates for the state of Florida, David had objected, and Congress by unanimous consent referred the dispute to the Commission.

“Gentlemen, rise for the oath!” Justice Clifford proclaimed. Clifford stood stiffly at the bench of the Court, before the center chair. There being, in Clifford’s view, no event too minor to endow with ceremonial significance, the senior Justice insisted upon being sworn in alone, by the clerk of the court, as Chairman of the Commission. Then Clifford led the members of the Commission in an entirely unnecessary oath, the same every man had previously sworn upon his entry into office.

“We now have before us the certificates relating to the electoral votes of the State of Florida,” said Clifford, once the members of the Commission resumed their seats. “Let us hear from the objectors to this first certificate.”

“If it please the Commission,” bowed David. “The result of the presidential election of November 7, 1876, in Florida was a majority in favor of Tilden. Nevertheless, the certificate signed by the then-governor of the State certified that Hayes had the majority. For one example of the sort of jugglery that result was accomplished, look to Baker County, where the county clerk — a Democrat — set out to count the vote of the county’s four precincts, assisted by a justice of the peace. The result was in favor of Tilden. Hearing of this, the county judge went to the sheriff and demanded that another man be appointed justice of the peace. The county judge, the sheriff, and the newly minted justice of the peace then entered the clerk’s office and insisted upon a recount, contending that they had heard — without any proof — that some votes had been cast illegally. These new enumerators then threw out two of the four precincts entirely, so that they could certify a final count in favor of Hayes! Following a recount of the Florida vote, it became apparent that Florida was won by the Democrat — Tilden. But against the weight of all of this evidence, the outgoing Republican Governor signed a certificate asserting that the state was won by Hayes!”

“We shall now hear from the Hayes objectors,” said Clifford.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Justice Clifford, and the members of this honorable Commission,” said Evarts. “I entirely dissent from Mr. David Dudley Field’s account of the facts with regard to Baker County. But if the Commission should like to inspect the returns in Baker County, why then you must also go to Jackson County, where Democratic poll-workers rejected 271 ballots cast for Hayes, and stuffed the ballot-box with votes for Tilden. And so on and so on.

“We are not here to defend fraud. But I do not believe that this Commission was ever intended, or has the power, to probe every allegation of fraudulent voting or canvassing. Shall this Commission seize the most absolute, independent, and unquestioned right of the States to appoint their electors in their own way, and allow two Houses of Congress to overrule them? If you go behind this certificate, you launch yourselves into a tumultuous sea of allegations of fraud, irregularity, and bad motive. There is no limit unless we draw the constitutional line narrowly.”

Clifford growled at this argument and turned to David. “Does counsel for Governor Tilden propose to offer evidence to support the allegations of fraud?”

“If the Commission pleases,” said David, rising and standing next to Evarts, “we would like to offer evidence at some stage of this proceeding.”

“Pardon me, Mr. Field,” Evarts said, placing his hand upon David’s broad shoulder. “We do not believe that this Commission has the power to review any evidence that was not already placed before Congress. And should my colleague here desire to ask the Commission to review any evidence that was before Congress, then Governor Tilden must offer it into evidence, one document at a time. Otherwise, the only evidence that is properly before the Commission are the four certificates signed by the Governors of Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Oregon, all for Hayes.”

“We object!” exclaimed David, shaking off Evarts’s fraternal hold. “I cannot conceive of anything more unjust than to require us to offer this evidence piecemeal.”

“I suggest,” Miller ventured, “that counsel more fully discuss the question raised by Mr. Evarts’s objection, which is whether any evidence will be considered by this Commission beyond that which was laid before Congress.”

“What!” Field hissed.

“I suggest a modification to Mr. Justice Miller’s proposal,” volunteered Garfield. “Counsel should also address the larger question of the scope of our powers as a Commission.”

This modified proposal instantly ignited profound disagreement among the members of the Commission, which dissolved into a fractious assembly of Senators arguing with Senators, Representatives arguing with Representatives, and Justices arguing with Justices. Field and Clifford pounced upon Miller straightaway.

“So, the Commission is to decide a presidential election based upon only four fraudulent sheets of paper?” Field nearly shouted.

“You cannot be serious, Brother Miller,” Clifford warned.

“I am merely suggesting that counsel for Hayes explain why we cannot go beyond the evidence that was submitted to Congress,” Miller explained.

“How can we ignore evidence of fraud?” Field demanded.

“We must proceed in a consistent and orderly fashion,” Miller said. “If one side wishes to introduce evidence of fraud to benefit Hayes, then the other side should be allowed to introduce evidence of fraud to benefit Tilden. The rule we apply to one must apply to both. Personally, I believe that if this Commission becomes a supervisory review board of every vote cast in each of these four states, then we shall be here forever. But we must decide how broad the scope of our powers shall be.”

Clifford pondered the suggestion for a moment. “I believe our Brother Miller has a point.” He looked past Miller at Strong, who nodded, then turned to his left and looked past Field at Bradley, who assented in similar fashion.

“Very well!” Field crossed his arms and pouted.

Clifford pounded the table to silence the discussion.

“Counsel for Governor Hayes may proceed with their objection,” he said.

Evarts nudged Matthews, who rose to speak.

“Mr. Justice Clifford and gentlemen of the Commission,” Matthews said. “The argument advanced upon Governor Tilden’s behalf is that fraud vitiates everything. But it does not. If my friend and opposing counsel, by some art or strategems that I know his guileless soul does not possess, should hoodwink me by fraudulent misrepresentation into voting for his candidate, I cannot retract my ballot, nor can any scrutiny set aside the result, because fraud upon private persons is sometimes insignificant when compared to public interests. If the inquiry is opened, it must be opened to all intents and purposes. It will not do to stop at the first stage in the descent — you must go all the way down to the very bottom.”

Matthews’s words hung in the air for several moments. Field was not at all convinced, but the Democratic Senators and Representatives shifted uneasily. If they had learned nothing else from observing the Republican Convention, it was that Matthews was a veritable undertaker for Hayes. Would it be entirely in the Democratic Party’s interest to permit the introduction of new evidence of fraud?

“It is getting late,” Evarts remarked. “If we might proceed with our objection on Monday, I would be most grateful, as I have business to attend to.”

“Business?” Clifford scowled. “On a Saturday evening?”

“There is no rest for the weary, I am afraid,” said Evarts.

Clifford dismissed the Commission for the day, and as the members rose to depart, Field pulled Miller aside and hissed in his ear.

“Did you see that?”

“Did I see what?”

“Evarts made some sort of signal to Garfield,” Field said.

“I doubt that very much,” Miller said diffidently. “You are imagining things. I must beg your leave, as I am due at a reception shortly.”

Field looked across the chamber and caught the eye of his brother David and knew at once that he had imagined nothing.

No one dared ask Conkling about any of the stories that circulated that season. He had directed his carriage all the way out to Edgewood for a light supper with Kate, and now the carriage was being driven back into the city.

“We are in for a memorable evening, I assure you,” Kate said.

“Every evening with you is memorable,” Conkling replied.

“I would say the same,” Kate said, “but I was speaking of our entertainment! I saw Carmen in Paris and can assure you that the music is sublime.”

“I have heard the opera is scandalous,” Conkling said.

“Perhaps it shall give society something else to talk about.”

The two smiled at one another, for to be the subject of incessant gossip is as burdensome as it is arousing. Kate heard the whispers at every reception, the subtle importunings of her acquaintances, but she revealed nothing to anyone.

“You can scarcely begrudge Washington its amusements,” Conkling said. “There must be some relief from conversations about the Commission.”

“That tedious Commission!” Kate sighed. “All to decide which of the two least inspiring men in the history of our Republic shall become the least inspiring President! How far we have come!”

Kate indignantly raised her chin, an impertinence Conkling found irresistible.

“We are indeed far from the days of Chase, Seward, Stanton, Bates, and Lincoln,” Conkling said.

“And that disgraceful Tilden,” Kate pouted. “There is talk, you know, that the Democrats in the House may filibuster the Commission’s recommendations.”

“The Democrats in the House can do nothing without the aid of Republican Senators,” Conkling said, rather offhandedly for Kate’s taste.

Kate peered at Conkling in the carriage, but it was too dark to read his face and discern his intention.

“I cannot imagine that any Republican Senator would join with the Democrats in the House to support Tilden,” Kate ventured.

Conkling crossed his arms over his mighty chest. “There are, you know, Republican Senators who hold Hayes in low esteem.”

“Of course,” Kate said. “The better man did not emerge from that convention.”

Conkling said nothing, for his wounds were still fresh.

“But surely,” Kate went on, “no Republican Senator would think of aiding the filibuster of the Commission in the House. That would make Tilden President.”

“There are some,” Conkling said, in as disinterested a tone he could muster, “who believe that Tilden won the election, and would prefer to run against him in four years, than to tolerate that mediocrity Hayes for even a moment.”

“Those men do not know their history,” Kate replied. “For Tilden made extravagant promises of support to my father at the Democratic convention in ’sixty-eight. He never made good upon those promises.”

“Would your father have accepted the Democratic nomination for President?” Conkling could not help but ask. “He was surely entitled to the Republican nomination.”

“I waited the entire night at the Fifth Avenue Hotel,” Kate said softly. “We thought that, at any moment, a procession would appear to hail his nomination. But Tilden perceived that his own self-interest lay with Governor Seymour, who in turn promised the governorship to Tilden, as if it were some child’s bauble. Tilden betrayed my father to suit his own interests. Tilden can profit no further from that betrayal.”

Conkling was silent for several minutes.

“I cannot be absent from the Senate,” he said finally.

“You can, if a lady requests your attendance elsewhere.”

Conkling shook his head. “Edgewood is too close. It is but a short carriage ride from the Capitol.”

“Baltimore, then. It is close enough to visit, but too far to return in time.”

“Baltimore?”

“I intend to visit Baltimore in the near future. You cannot expect me to do so unattended.”

Conkling stared at Kate for several moments. If he remained in Washington, he reflected, he could ride into battle, lance at the ready, and revenge himself against Hayes. What would become of that lance if he retreated to Baltimore?

“I shall reward you if you do,” Kate persisted.

“Your thanks would be its own reward.”

“Then shall you escort me to Baltimore?”

Conkling looked out the window of the carriage. They were traveling the streets of the city, its buildings, monuments, and lights. At Edgewood there were no temptations other than Kate, but now in downtown Washington, there was the sting of contrary obligations. The thought of that inconsequential cipher Hayes as President would be nearly unbearable. But Hayes had promised to serve only one term, and to violate that vow would be a breach of trust so great that he would be surely defeated for renomination. Conkling would be equally at liberty in ‘eighty whether Hayes or Tilden prevailed now. And he would have Kate in the meantime.

“I shall do as you ask.” Conkling turned from the window of the carriage and looked Kate in the eye.

Kate gazed at him apprizingly for a moment, for he had taken too long to decide, in her opinion. But now her face lit with a deep satisfaction.

“Here,” she said. She turned to a bouquet of flowers upon the seat beside her and removed one flower. Lightly, she tossed the flower from her side of the compartment to his. Conkling looked at the flower quizzically, then placed it in his buttonhole.

It had been Evarts’s intention to begin his argument with some jocularity, on the belief that a sprig of good humor might sweeten the bitterness common to Monday mornings, particularly in the last grey days of winter.

“My learned adversary Mr. David Dudley Field asserts that documents that were not put before Congress ought to be accepted as evidence,” Evarts declaimed. “But I have never heard of a party at law who can turn anything into evidence merely by appending it to his papers. Evidence must be properly offered by counsel, and ruled admissible by the court, or in this case the Commission. We cannot simply accept these documents without knowing what they contain, whether they are authentic, or what they may prove or not prove.

“And there is an additional complication — whether Congress itself could accept this material in the first place. Why, it cannot! Neither Congress, nor by implication this Commission, can receive any additional evidence beyond the certificate duly signed by the Governor of Florida. Congress has no power to decide whether the electors sent by the states are qualified.”

“Suppose the canvassers had made a mistake in adding up the returns,” Justice Field interrupted, “and suppose that mistake changed the result of the election, and that they discovered it before the electoral vote was counted, would there be no remedy?”

“There would be no remedy, Mr. Justice Field,” Evarts replied.

“Then a mistake in arithmetic may elect a President of the United States and Congress would be powerless to prevent it?” Field asked.

“Correct,” Evarts replied, serenely.

“Suppose the canvassers were bribed,” asked Field, emboldened, and with a glance at Bradley, “but the fraud was detected and exposed, would there be no remedy?”

“No,” Evarts said. “Whatever fraud there is must be discovered and protested against before the board of canvassers makes its returns.”

“But suppose the members of the board were themselves conspirators?”

“It makes no difference under the law.”

“Suppose the canvassers were coerced by force,” Field’s voice was now very loud, even for such a large chamber, “suppose men put pistols to their head and threatened to blow out their brains if they did not perjure themselves, would there be no remedy?”

“No.”

Field sat back with a smile of triumph and looked about the table. The Democratic Commissioners were nodding their heads with conviction; the Republican Commissioners did not seem perturbed by the directness of Evarts’s answers, but Miller and Strong surreptitiously exchanged anxious looks.

“Thank you, Mr. Evarts,” said Clifford. “That concludes the arguments of counsel as to whether this Commission should accept evidence of fraud.”

“I believe you mean to say,” Miller interjected, “whether the Commission ought accept evidence that was not submitted to Congress.”

“It is all the same,” Clifford harrumphed.

“I beg your indulgence, Mr. Justice Clifford,” said Garfield. “Perhaps we can vote now upon the question?”

“I would rather that we have some time to consider the matter,” said Clifford, with an unmistakable stare in the direction of Field, who nodded slightly. Miller followed Clifford’s stare but could not for the life of him conjure what the Devil those two were up to.

The men of the Election Commission filed in silently the following morning.

“I hereby order the doors of this chamber closed!” Clifford boomed. “I shall not tolerate any disruptions to the work of the Commission.”

Clifford waited until the Old Senate Chamber was entirely secure, and there was no prospect of interlopers secreting themselves about the room to be the first to learn whether Tilden or Hayes commanded the greater sympathy.

“Is this entirely necessary?” Miller murmured to Clifford. “We shall be treated to nothing but congressional speechifying to-day. This chamber shall be no different from the public galleries of the House or Senate.”

“I shall not suffer any outward interference,” Clifford said to Miller. “Only the members of the Commission shall know how the votes are cast.”

“I am fairly certain anyone could predict how the Senators and Representatives shall vote to-day.”

“Gentlemen!” Clifford cried, ignoring Miller. “We shall now proceed to the vote. You may take all the time you wish in stating your vote and the reasons therefor.”

Miller rolled his eyes but took his place without further objection. Clifford having rebuked his suggestions, and Field being hostile to any procedure that might disfavor Tilden, Miller turned to Strong, who was seated at the end of the line of Justices with their backs to the bench.

“We really ought to have brought some opinions to work on,” he said. “If you give a politician as much time as he likes, he shall take every last second.”

“I came prepared,” Strong smiled, and produced a small Bible that fit neatly into his palm. “I would be happy to share it with you from time to time.”

“I’ve read it already, thank you.”

Over the next few hours, Miller came to regret declining his colleague’s offer of reading material. For it was the tradition of the Senate that no point, however trifling, could be disposed of without extravagant speechifying. The five Senators upon the Commission availed themselves of every rhetorical device, and considered every argument in all its complexity, in arriving at precisely the conclusion that anyone could have anticipated — the three Republicans went for Hayes, and the two Democrats went for Tilden. Strong, meanwhile, had made his way from Genesis all the way through Isaiah.

“The members of the Commission from the Senate having voted,” Clifford intoned, “the Commission stands at three votes against considering additional evidence, and two votes in favor. We shall now hear from the members of the Commission from the House!”

Miller was by now nearly beside himself with boredom.

“Brother Strong,” he nudged his colleague. “Might I trouble you to borrow your Bible?”

Strong hesitated to reply. “If I may, Brother Miller, I am nearly at the Gospels, and . . . ”

“Fine.” Miller crossed his arms.

The members of the House then proceeded to address the momentous question consistent with their own oratorical tendencies, in equal parts passion, logic, derision, and exaggeration. The element of suspense, however, could not be maintained, as each of the Republican Representatives voted for Hayes, and the Democratic Representatives for Tilden. At the end of a very long day of speeches, the vote against admitting additional evidence was five against four, with Representative Payne of Ohio, a Democrat, yet to vote.

“The hour is now late,” Clifford said. “With all due respect to Representative Payne, I believe we must wait until tomorrow to hear his vote.”

There was unanimous assent to this proposal.

“I would like to raise a procedural point,” said Field, as fourteen pairs of weary eyes turned in his direction. “My brethren and I shall be casting our votes and explaining our positions tomorrow. I would request that I be permitted to read first. As the Chief would vote last at conference, so Brother Clifford would vote last here.”

Miller raised an eyebrow. The more natural order would be to require the junior justice to speak first, and that would be Bradley. What reason did Field have to speak before Bradley? he wondered.

“I am amenable to proceeding in that fashion,” said Clifford, who was of course pleased to have the final, and possibly deciding, vote on the matter. “Is there any objection?”

Miller began to object, but he could articulate no grounds and fell silent. Of the congressmen assembled at the table, only Garfield appeared troubled by Field’s suggestion.

“The Justices shall vote tomorrow,” said Clifford, “with Brother Field leading, and the Chairman of the Commission voting last. Good evening!”

Strong snapped his little Bible shut. “Almost at the end!” he said. “I have a few epistles left before the Book of Revelations.”

“That is certainly the best part,” Miller said, but now fell into a whisper, as the members of the Commission prepared to depart the chamber, “but do you think that we should have a few words with Bradley?”

“For what reason?”

“I am concerned,” here Miller eyed Bradley as his colleague tidied his papers, “that there may be some effort to influence Bradley of which we may not be aware.”

“I very much doubt that,” said Strong. “Bradley is his own man.”

“I suppose,” Miller murmured, not entirely satisfied but uncertain whether there was any basis for an approach. By the time he turned around, Bradley had departed.

A few feet away, Garfield considered closely what he had overheard. He took a few rapid strides to his fellow Republican, Senator Frelinghuysen of New Jersey, seized him by the elbow, and began to speak very intently in his ear.

The Commission gathered the next morning, determined and grim. There would be other matters to address, and other states to consider, but the vote on the admissibility of evidence concerning Florida would set a precedent for the entire work of the Commission. Representative Payne cast his vote first, with most intemperate remarks regarding the manner in which black men had voted in Florida, in favor of the admission of evidence. The vote stood evenly, five against five.

It was now the turn of the Justices, whose votes would decide the election.

Field fixed his spectacles and began to read his opinion in a firm, clear voice.

“The main question submitted to us,” Field said, “is whom the State of Florida has appointed as electors to cast her vote for President and Vice-President.”

Field went on to describe the manner in which the canvassing boards had most unjustly discarded the votes of Tilden supporters and then attacked the contention of the Hayes men that nothing could be done to address this grievous injustice.

“The position of these gentlemen,” Field exclaimed, “is that there is no remedy, however great the mistake or crime committed. If this be sound doctrine, if the representatives in Congress of forty-two millions of people possess no power to protect the country from the installation of a President through mistake, fraud, or force, we are the only self-governing people in the world held in hopeless bondage at the mercy of political tricksters. The country may submit to the result, but it will never cease to regard our action as unjust.”

Field set down his papers and leaned back in his chair with a triumphant grimace. With his vote, the total now stood six to five in favor of admitting evidence of the fraud in Florida. Tilden was for the first time favored to win the Presidency.

The hopes of the Democrats on the Commission, however, were soon tempered. Strong spoke next, and his plain-spoken and direct manner left little doubt where he stood.

“The scheme of the Constitution,” Strong explained, “was to make the appointment of electors exclusively a State affair, free from interference of the legislative department of the Government. It follows, in my judgment, that the evidence now offered is impertinent to any question we can decide, and, therefore, that it ought not to be admitted.”

The Commission was again divided evenly, six against six. It was now Miller’s turn.

“The only question which I consider to be properly before the Commission,” said Miller, “is whether any additional evidence can be received and considered by the Commission than that which was submitted by the President of the Senate to the two Houses of Congress. I vote that none of the evidence offered by Tilden in this case, outside of that submitted to the two Houses of Congress, can be lawfully received or considered by the Commission.”

The Commission now stood at seven to six against the admission of additional evidence, and therefore in favor of Hayes. Only one more vote was necessary to set the Commission down the inexorable road to a Hayes presidency.

The chamber fell silent. While not yet cast, Clifford’s vote in favor of admitting evidence, and thus in favor of Tilden, was assured — thus there would be seven votes for and seven votes against. Bradley’s vote would determine the outcome. Most of the members of the Commission stared straight at Bradley; Garfield and Frelinghuysen both stared directly at the floor. As Miller cast his eyes about the room, he fancied he perceived a glint in Field’s eye, and a slight smirk playing around the edges of Clifford’s mouth.

Bradley gave a quiet, dry cough and began to read.

“The first question is whether Congress has the power to inquire into the validity of the votes. How far can the two Houses go in questioning the votes received, without trenching upon the power reserved to the States themselves? Can Congress institute a scrutiny into the action of the State authorities and sit in judgment on what they have done?”

This would surely seem to portend a victory for Hayes, the Republicans thought.

“But at the same time,” Bradley said the next moment, “must Congress submit to outrageous frauds and permit them to prevail? Certainly not, if it is within their jurisdiction to inquire into such frauds.”

Now the Tilden men exhaled in relief, while the Hayes men muttered amongst themselves angrily. No sooner had Bradley pursued one question to the favor of Hayes, it seemed, than he raised another question in favor of Tilden.

“But there is the very question to be solved. Where is such jurisdiction to be found?”

By now, nearly all of the members of the Commission were stricken with nerves, while Bradley, quite immune to the agony he was inflicting, suddenly arrived at a most abrupt conclusion.

“It seems to me to be clear, that Congress cannot institute a scrutiny into the appointment of electors by a State. We therefore cannot accept additional evidence.”

Miller involuntarily let out a low whistle. The presidency would now almost certainly go to Hayes. Miller perceived a hiss. He turned to his left, and saw Field trembling with rage, and Clifford with reddened face, his eyes blazing at Bradley. It was apparent that he harbored some resentment against his fellow jurist, not the least of which that, having voted to exclude the evidence and setting the vote at eight to six, Bradley had rendered Clifford’s vote irrelevant. Yet relevance had not previously been a constraint upon Justice Clifford and would not be so now.

“I shall now give my opinion,” he said.

Clifford’s opinion was as predictable as Bradley’s was unexpected. Opining at a length to which his colleagues had long been accustomed, but which came as an unpleasant surprise to the other members of the Commission, Clifford began by describing the proceedings in extended detail, the arguments of counsel and the determinations of procedure in the state courts.

“Certifications for Tilden,” Clifford eventually concluded, the wattles of his neck turning red and shaking violently, “are supported by confirmation strong as proofs of Holy Writ. Weighed in the light of these considerations, the proposition that subsequent investigation cannot be made is monstrous, as it shows a mockery of justice!”

The men could now hear the low rumbling of impatient voices behind the door separating the chamber from the corridor.

The votes with respect to Florida were recorded, at eight to seven against the admission of additional evidence of fraud.

“Adjourned,” muttered Clifford.

With that, Frelinghuysen and Garfield strode quickly out of the chamber. There was a sudden hush as the men opened the door to the corridor, then renewed mutterings, followed by cries of anguish and exaltation. The remaining Senators and Representatives rose to meet a number of their colleagues who had been waiting outside the chamber for the news of the Commission’s decision. Soon only the five Justices remained. Clifford sat still and stony at the head of the table and Bradley looked down at his opinion as he gathered his papers to leave.

Field uttered a profanity of such blasphemous import that decency forbids its repetition. Bradley did not look up.

“Brother Bradley,” Field insisted. “Is there anything you wish to explain to me?”

“I do not believe so,” Bradley said.

“Really?” Field slowly laid one palm down on the table, then another. “I am compelled to disagree with you.”

“I regret to hear it.”

“Regret?” Field said, in a near whisper. “You offer regret? You have lied to me, and you have nothing but regret?” Here his voice began to rise. “Not shame? Not fear of the dire consequences of your most outrageous deceit?”

“Now, Brother Field — ” Miller sought to intervene. He glanced anxiously at Clifford, but Clifford remained with his gaze fixed upon Bradley while a short man, who had entered the chamber unnoticed, whispered in Clifford’s ear. Clifford’s face grew more flushed.

“Do not speak to me!” Field snarled. “My business is with Brother Bradley, not you! I may disagree with you, Brother Miller, but I do not question the honesty, or integrity, of your decisions. You may be wrong a great deal of the time, but you have backbone! This man” — here Field turned his anger back to Bradley — “is a spineless, lying wretch.”

“Brother Bradley,” Clifford interrupted. The sound of his voice was ominous, such that Field ceased his diatribe and Bradley finally looked up, a pained expression on his face. “Will you not agree that you prepared your opinion in this matter over the weekend?”

“I prepared an opinion, yes,” Bradley said, quietly.

“Will you not agree that you showed your opinion in this matter to me and Brother Field on Monday evening?”

“What?” Miller exclaimed.

“I showed an opinion to you and Brother Field that evening, yes,” said Bradley.

“And do you not agree that the opinion that you permitted Brother Field and I to review on Monday evening was an opinion that the Commission should accept additional evidence of fraud affecting the election in Florida?”

“That is true, but — ”

“I am the Chairman of this Commission. Permit me to finish,” Clifford said sharply. “And do you not agree that the opinion that you read here to-day reached precisely the opposite conclusion?”

“Yes, but — ”

“You changed your vote?” Miller blurted. “Why?”

“That is precisely the subject of my concern,” Field said.

Clifford raised one hand. “I believe that I am now in possession of such information that may shed some light upon the matter.” Here Clifford nodded to the short man who had been whispering in his ear, and who nodded back, and departed. The five Justices were now alone again in the chamber.

“I believe, Brother Bradley, that you entertained some callers last night.”

“There were some callers at my home, yes.”

“Some! Was it some, or was it many?”

“Surely I am not prohibited from entertaining callers at my home, Brother Clifford,” said Bradley.

“You may entertain whomever you like. But I intend to ask you whether you promised them anything, and whether they promised you anything in return.”

“I do not have to answer any of these questions,” said Bradley, and began to rise from his seat.

“The chairman of this Commission is asking you about your actions as Commissioner!” Field nearly shouted. “You shall sit down, Godd__n it!”

Bradley promptly resumed his place.

“I shall handle this, Brother Field,” said Clifford. “We have been told that several men called upon you, several Republicans and even other members of this Commission. Is that not true?”

“It is, but I hardly see the relevance.”

“Senator Frelinghuysen visited, did he not?”

“He did, but we are old friends from New Jersey.”

“As did several railroad men, including representatives of the Texas & Pacific Railroad. Correct?”

Field inhaled sharply.

“You must remember,” Bradley said evenly, although his hands shook, “I was a lawyer for the railroads before I joined the Court.”

“For the Camden railroad, if I am not mistaken!” Now Clifford’s voice rose. “You were never a lawyer for the Texas & Pacific!”

“That is where he rides Circuit,” Field rasped, before Bradley could say anything. “You have no social connection with these men — you know them only because they have matters pending before you in Texas. Now it all fits together!”

“I am offended at the suggestion, Field — ”

“What did the railroads promise you in return for your vote?” Field pounded upon the table. “Or did you take something from them long ago, and they called to remind you that you were still on their retainer!”

“Good heavens, Field!” This was quite enough for Miller, but Strong sat silently, and Clifford showed no inclination to rein in his colleague.

“They did not influence me at all,” Bradley replied sternly.

“Do you take us for fools?” Field thundered. “Your vote was one way on Monday evening, then switched to entirely the opposite position after Tuesday evening, but it had nothing to do with your visitors?”

“Not at all!”

“Brother Bradley,” Miller interjected, “I cannot help but express my surprise that you changed your mind so dramatically — as is your right,” he said loudly, raising one hand to silence Field. “But you do owe us an explanation. What in good heavens changed your mind?”

Bradley was silent for a moment.

“Well, that is the very thing. I prayed on the matter.”

“You prayed?” howled Field. “You prayed? Do not take the name of the Lord in vain here and invoke his holy name to bless your iniquity! Did you kneel down next to the men of the Texas & Pacific Railroad, and bow your heads in supplication together?”

“Field!”

“Whom did you pray with, that your heart was so changed? Was none but the Lord present?”

“Well, no.”

“D___, Bradley!” Field shouted. “With whom did you kneel in prayer that your mind was changed?”

“None but my wife.”

“Your wife!”

“Mrs. Bradley?” Miller exclaimed.

“Yes, my wife,” Bradley said stiffly. “Can a man not pray with his wife?”

“And did Mrs. Bradley have any view as to how you ought to vote?” asked Clifford, with no small measure of scorn.

“Yes,” said Bradley. “Yes, she did. What of it? She is entitled to her opinion — she is the daughter of a Chief Justice.”

“Of New Jersey!” Field laughed uproariously for several moments. “So, it was her? She made you change your vote?”

“My vote was entirely my own!” Bradley objected.

“Oh, I see!” Field crowed. “Your vote was your own, but your wife told you how to cast it!”

“Not at all!” Bradley struggled for words. “She did, I suppose, influence me to some extent, but — ”

“She influenced you as the moon influences the tides, as the sun influences the rotation of the celestial spheres, as the transit of Venus ordains the fates of men!” Field crowed. He stopped for a moment, then his face broke into a wide grin of recollection. “How out of keeping with the natural and proper timidity which belongs to the female sex!”

Bradley’s eyes narrowed. “This mockery is beneath you.”

“Mockery?” Field feigned incredulity. “I am merely surprised, that is all! I recall a very wise jurist advising that the constitution of family life, founded in divine ordinance and the nature of things, reserves the domestic sphere to the domain and function of womanhood! That same esteemed scholar of the law — whose name I recall to be very similar to yours — instructed that the harmony of the family institution is repugnant to the idea of a woman adopting an independent career from that of her husband! I am happy to see that here, there is but one force directing the movements of your family!”

“I will not listen to such outrageous insults!” Bradley finally stood and angrily stuffed his papers into his satchel. “Good day, gentlemen — and Field!”

Bradley’s impotent rage did little to dispel Field’s air of scornful bemusement.

“We shall soon be fitting Mrs. Bradley for her robes!” he exclaimed, as Bradley departed the chamber.

Justice Field stood alone in the center of the Old Senate Chamber, his back to the bench of the Supreme Court, in contemplation of the bust of Chief Justice Marshall. The likeness was adequate, he reckoned, compared to the portraits of the Chief he had seen, but the Court had done its greatest Chief a severe injustice by commissioning a bust so long after Marshall’s death. The passage of time and the fading of memory had stunted the flower of the sculptor’s art. He would do well, Field resolved, to arrange for a sitting while he was still alive.

He heard his brother’s heavy tread and labored breath behind him.

“Well?” Field demanded.

“There was an unforeseen complication.”

By way of directing his brother to continue, Field unleashed a series of vituperations so unparalleled in the history of that storied chamber that one half expected the bust of Chief Justice Marshall to weep for shame.

“I would never have sent you to California had I known you would return with such a foul mouth,” David remonstrated.

“I would never have arranged to have you serve as counsel for Tilden had I known how poorly you would perform,” Field replied.

“This is hardly my fault. You were supposed to have persuaded Bradley.”

“I thought I had,” said Field sourly. The Democratic House had rejected the Commission’s decision, the Republican Senate promptly accepted it, and the decision of the Commission awarding Florida’s electoral votes to Hayes stood.

“We can still prevail even if we lose Florida,” said Field, “but I cannot accept losing Louisiana by another vote of eight to seven. There the frauds were even more egregious. Is a great nation to submit to all this? Must forty-five millions of people drink from a foul sink the ordure that flows through such a fetid sewer? Truth ought to be permitted to shine upon this transaction, and if truth shine upon it, there can be but one result!”

“I fear that we shall lose every vote on the Commission by the same margin,” said David.

“I am well aware of that,” said Field crossly. His condemnations of Bradley had not prompted the latter to reexamine his course, not in the slightest.

David sighed. “Our friends in the House discharged their duty and rejected the decision of the Commission with regard to Louisiana. The Democratic newspapers whipped them to it, suggesting that as to Louisiana in particular, there need only be a few fair-minded Republican Senators to agree to a resolution naming Tilden as President and ending the work of the Commission.”

“You cannot trust the Republican Party to be fair!” Field complained. “You must appeal to their interests!”

“Rest assured that you cannot conceive of any device of persuasion that I have not already employed. There was one Senator in particular, an influential one, whom we thought might be most amenable to a filibuster.”

“Your friend from New York?”

“The same. If Tilden became President, he would be a weak one, and his term could merely be a prelude to a Grant restoration, which is attractive to our friend. He is also impatient with the idea that the Democrats could be bought off with money for improvements in the South.”

“Then your friend should filibuster the result in the Senate!” Field threw up his hands in frustration.

“It is more complicated than that. A filibuster in the Senate could prolong the dispute past the time that Grant would vacate the office, so that the new President of the Senate might ascend to the Presidency, according to the line of succession.”

“Then your friend could be elected President of the Senate! Either way, our proposal benefits him as much as it does us.”

“It doesn’t,” David said. “Blaine will be sworn in as Senator on the fourth of March, along with that d___able Hayes man Matthews.”

“So?”

“Blaine was Speaker of the House. One cannot count him out as a candidate for President of the Senate. Our friend from New York would not take the risk that his filibuster would result in Blaine becoming President. And then there is the railroad money.”

“But these Democrats should not be bought off so easily!” Field exclaimed. “I am here fighting for the office of the Presidency, not some third-rate postmaster position!”

“Nearly one half of the House has either not been re-elected or has determined to return to private life. These men have less than one month to fatten at the trough. Can you blame them?”

“But the House rejected the Commission’s decision.” Field brushed his brother’s argument aside. “We have accomplished that much. Why was there no filibuster in the Senate?”

David began to laugh ruefully.

“It appears,” he said. “That in all our considerations of politics we neglected to consider a more elemental motivation. The Senate galleries to-day hosted an entire occupying army of office seekers, relying upon the inauguration of a Democratic President for their livelihood. We all thought that the defeat in Cincinnati might be avenged, and the man unjustly overlooked at that hour would return to prevent the election of Hayes. But he did not filibuster the decision of the Commission. He did not even appear for the vote, which upheld the decision of the Commission, allowing the electoral votes of Louisiana to count for Hayes.”

Field was aghast. “What? Where was he?”

“Well,” David drawled, “Senator Conkling was detained in Baltimore. For he had apparently made a promise to a lady, and the only decent thing was to keep it.”

Waite could remain in his rooms no longer. The entire month of February had been cold, dark, lonely, and unpleasant. He was running the Court on his own. Five Justices were occupied with the Commission, Swayne often absented himself on excuse of his age, and Hunt complained so continually of the gout that Waite had ceased making any requests of him altogether. Davis was readying his departure, for even if there was no President selected by the fourth of March, the Senators elected in November would be obliged to begin their terms, and Davis would be among them. Waite eventually roused himself and determined to seek out Evarts.

Upon arriving at Wormley’s, however, Waite was besieged in the lobby by an uncommonly large number of gentlemen. Finally, Wormley himself, a cordial older man of mixed racial complexion, rescued the Chief Justice from the melée and personally escorted him to an upstairs room.

Wormley rapped on the door.

“Go away!” cried Evarts from within.

“Good evening, sir, it is your proprietor,” called Wormley with a mischievous smile. “And a friend.”

After some moments, Evarts opened the door. His long nose was nearly scarlet, his face was gaunt and unshaven, and his necktie undone.

“Please, accept my apologies,” Evarts waved his hand toward a ring of chairs arranged around a central table. The air was thick with the smoke of cigars.

“You shall have to arrange a proper cleaning, I am afraid,” Evarts said to Wormley. “It was too cold to open the windows.”

“Understood, sir.”

Waite sat down, uncertainly. There were several glasses of unfinished whiskey about him, some with cigar ashes floating about in the liquor. Wormley remained standing. “I shall fetch you a fresh whiskey.”

“Perhaps you might find us some coffee, instead,” Evarts said absently. Wormley bowed and left the room.

“I have had enough coffee for the time being, thank you,” Waite said.

Evarts took a long, slow look at his friend.

“You must understand that everything I tell you must be kept in the strictest of secrecy. As strict as the oath of secrecy that bound us to our society at Yale.”

Waite laughed. “Is the matter that serious?”

Evarts startled, paused, then continued.

“You find me here in this condition because, as you must know, there was some threat that the work of the Commission would be undone by a Democratic filibuster of the South Carolina vote.”

“I have been working steadily and have not any opportunity for dinner party conversation,” said Waite.

“The filibuster was avoided through the most indecent series of promises that I have ever witnessed. Over the past day or two, a parley was held here. Representing Hayes were Garfield, Matthews, myself, and some others. And on the other side were representatives of the Southern states. We met in anticipation of members of Congress from the Southern states mounting a filibuster against the Commission results. To ensure that there would be no filibuster, we formalized certain commitments.”

“Such as?”

“Such as withdrawal of the Union troops currently in those states,” Evarts looked at his hands.

Waite was amazed. “How could you ever promise that?”

“Because the man most likely to become our next President authorized the very thing. There were also promises made for the financial support of the Texas & Pacific Railroad.”

“But the withdrawal of the Union Army is the same thing as handing over those states to the Democratic Party.”

“Perhaps,” said Evarts heavily. “I console myself thinking that this will happen in any event, and that our agreement here simply confirms what everyone already knows — that the Democratic Party is willing to accept Hayes’s election provided it is allowed to return to power in the states of the Confederacy.”

“A corrupt bargain!” gasped Waite.

“It may also undo any progress that has been made for the Negroes in those states.”

“What need is there to make these concessions, when the Commission has concluded that Hayes is the victor?”

“The Commission is merely one of the pieces on the board,” Evarts said. “It cannot achieve the result entirely upon its own. There is a profound need in the nation for reconciliation, and the decisions of a Commission cannot alone achieve that goal.”

“That is profoundly distressing,” said Waite. “Can you be sure they will keep their side of the bargain?”

Evarts looked away. “It is likely that I will be the next Secretary of State, and Sherman the Secretary of the Treasury. I do not know what Garfield or Matthews want.” He snorted. “This assumes, of course, that Conkling does not oppose me again. And there have been promises that other men shall get nothing or shall be asked to resign. Bristow, for example, will get nothing, on account of his investigating Grant’s friends implicated in the Whiskey Ring — that was Hayes’s personal proposal to Grant. And the United States Attorney in Louisiana shall have to resign. Some fellow named Beckwith, who prosecuted the Cruikshank case before your colleague Bradley. One of the Southern gentlemen — a Mr. Ellis — represented the defendants in that case and felt strongly upon the subject.”

Waite paused. “Well, at least you will have the power to make things right and assure that the Republican governments do not wither away entirely in those states.”

“I cannot be too sure,” said Evarts. “I am reminded of when I cast my vote for Mayor of New York, back in ‘seventy. The Tweed Ring had rigged the entire election. When I walked in and gave my name, the clerk told me that that I had already voted!”

“Had you voted?”

“I had not.”

“What did you do?”

Evarts smiled grimly. “I said, ‘Indeed? I hope I voted right!’ ”

“The nomination is an affront to the Republican Party,” said Conkling. He had taken off his jacket and was stalking about his Senate offices in a bright yellow waistcoat, his face flushed crimson with an anger darker than the color of the hyacinthine curl upon his forehead. “It is an insult to every man who devoted his efforts to the election of His Fraudulency.”

Upon the vacancy of the new Senator David Davis from the Supreme Court, President Hayes had nominated John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky.

“I do not think your tone is appropriate,” said Stanley Matthews. Matthews, lately elected to the Senate by the legislature of the State of Ohio, had been summoned by Conkling in a fit of anger, and was sitting in front of Conkling’s desk, like an errant schoolboy called before the headmaster. Representative Thomas Platt sat upon the edge of Conkling’s desk with his arms crossed, glaring at Matthews.

“You are a recent arrival to our institution, Senator, so permit me to explain how things are done here,” Conkling said. “There is a principle most essential to the complementary relations between the Executive and the Senate. That is the principle of consultation. The failure to abide by this principle has led your friend in the Executive Mansion to make two different sorts of mistakes. The first mistake is with this Harlan nomination. Harlan is not only entirely unsuited for the position but represents the elevation of the so-called Reform element of the party above the interests of its most stalwart supporters. The second mistake is with the Customs House nominations, as to which I was not consulted.”

In Conkling’s view, Hayes had taken egregious liberties in nominating men of the Reform faction to positions at the New York Customs House, among them a naval officer named Edwin Merritt as Surveyor, and a Knickerbocker named Theodore Roosevelt as Collector. Merritt was sent to New York to advise Chester Arthur that the latter was being relieved of his duties and, one July afternoon, duly apprised Arthur of the changing of the guard. Arthur did not take the news at all poorly, but rather chatted pleasantly with Merritt, secure in the belief that Merritt’s tenure would only last as long Congress was out of session. And when Hayes directly asked Arthur for his resignation by telegram, Arthur politely declined to provide it.

“Which nomination constitutes the greater affront to your dignity?” said Matthews, too dryly for Conkling to notice.

“It is not too late to withdraw the Harlan nomination,” Conkling continued, crossing his arms over his mighty chest and turning toward the window, the sunlight falling upon his fine profile as upon a statute of Apollo.

“The man is scarcely a Republican,” said Platt.

“There was no Republican party to speak of in Kentucky until Harlan helped build it,” said Matthews, “and he was wounded fighting for the Union.”

“Your man Bristow was wounded at Shiloh,” Platt interrupted, “perhaps the President should nominate him?” Platt and Conkling laughed.

“The Senate should judge General Harlan upon his own merits.”