The autumn evening in The Hague is cooling as I lean my bicycle against the steel stairway and step into the brightly lit atelier. It’s tucked in the corner of a green-colored building on Noordeinde, at the bottom of the long street leading up to the Dutch king’s palace.

Inside, several women are talking in Spanish or Dutch, laughing, drinking from wine glass or ceramic cups. Two women are working at narrow, waist-high stands, kneading or slapping grey shapes. From a small stereo on a corner shelf rise Cize Évora’s throaty morna laments.

My teacher, Anat, rises from her wood stool, stubs out her cigarette, and greets me. She radiates energy and I feel a buzz. For the last few months, I have been drawn to Anat’s magazine ad for sculpting classes. Living here in Europe, my emotions are stirred by Giacometti’s gaunt black figures, Brancusi’s cubist bronzes. I am moved by Rodin’s sensuous hand sculptures and ribald busts of Balzac. These artists are worlds apart in their expressions, but they all speak to me. Now I feel that the rich, red soil of the island I grew up on is also speaking to me, and I need to get my hands on clay.

Anat shows me around her small, cluttered art space. On the largest wall hangs a framed painting by de Lempicka. It’s a wide-hipped, almond-eyed nude in glossy yellow, blue, grey, and black oils. On a wood beam nearby hangs a framed sepia photo of an old couple wearing traditional Middle Eastern attire. Beside it is a black and white photo of a young woman in soldier’s gear. She is holding a semiautomatic rifle and looks fierce. That’s me, says Anat.

Black resin and red clay busts of van Gogh rest on an acrylic pedestal. Wall shelves display cloth-covered bowls, boxes of rags, trays of tools, balls of string, and newspapers. Under the shelves are small crates of rough soapstone and jade alongside stacks of short square logs. Each log is wrapped in plastic. This is the clay I will learn to sculpt.

Anat invites me to pick my tools. I select doll-sized wood scythes, a garrote and a wire loop, an oval rubber scraper. These tools seem right although I have no design in mind.

On an unoccupied worktable she places a small turntable with a fixed metal armature. We wrap damp newsprint into a fat cigar shape on the vertical rod and secure it with string. Anat slits a package of the light-grey clay. It feels moist and slightly tacky, like hard tofu. It smells like chemicals, soil, and something verging on animal waste. I stifle a powerful impulse to lick it.

Anat cuts a thick slice of the clay and halves it, squeezing and thinning each portion with her slender fingers. She presses a piece in place on the armature. I add another and we quickly shape a human neck. She garrotes and indents a new piece of clay to make it slightly concave and hands it to me. It seems alive in my palms. I hold it to my nose, inhale the heady aroma, then press it on the armature and shape it into the back of a skull. My hands seem to know what to do.

Anat guides me to shape the rest of the cranium and the face, forehead, and jawbone. I add smaller pieces to form the figure’s cheeks, nose, and eye sockets. We smooth and blend and scrape the seams. She shows me how to shorten and reshape the chin, so it is in proportion to the jawline and its distance to the brow.

We are working rapidly. The clay is pushing us. The air vibrates with the other artists’ hubbub and the Portuguese singer’s plaints. Incense wafts from a stick standing in a sand pot on Anat’s desk.

I push and pinch the clay into a broad septum and flared nostrils. With a flick of her veined wrist and long forefinger, Anat indicates how I am to scoop the small nasal passages. I create full lips and gently press my baby finger into the upper lip to shape the ski slope philtrum.

Anat shows me how to shape and place a pair of ears that fit this figure’s proportions. Then I scrape and indent temples on the forehead, rub the sensuous curve of the skull to remove scabs of dried clay. She nimbly shapes and softly presses eyeballs into the sockets. Petite half-moons become eyelids. After fussing with the shape to correct its curves, she steps back.

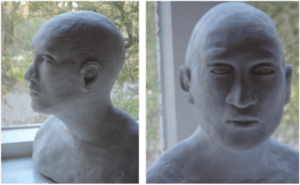

A male figure has emerged from the clay. I stare at Anat. She grins and does a little skip in her stiletto boots. Slowly we rotate the armature on the small tabletop. Do I want to add hair on his head, asks Anat. No, he seems to be from a different place and time. A queue is more fitting.

After considering how to shape and where to place the long braid, I reach for new clay and my elbow pushes the figure’s nose slightly off center. I feel upset until I see that the distortion has given him a story.

After considering how to shape and where to place the long braid, I reach for new clay and my elbow pushes the figure’s nose slightly off center. I feel upset until I see that the distortion has given him a story.

This is a young warrior. He was taken captive during combat, his nose broken, and his queue cut off to humiliate him. But his defiant look rejects the indignities. I tell this to Anat. She lets out a loud belly laugh, her red lips wide. Some of the women are listening to us.

A strange sensation has been building deep inside me while Anat and I worked. It is a force, not a feeling. Something primal. Now I am seized by a powerful physical desire to eat the clay. I want to rip sticky chunks and fill my mouth, mash them with my molars, feel gobs slither down my throat. I want the clay’s animal smell to turn into a flavor on my tongue then consume me.

There is a rush of energy from my gut to my hands. Heat seems to be rising in waves from Anat and from the other women. It is pulsing from the clay, too. My heart starts to thump. I want to scream. Instead, I hide my turmoil and get up, put on my sweater, give Anat a teary hug. I must go, I say. Something is happening to me; I don’t know what it is.

Her sparkling eyes hold mine. She grabs both my hands and squeezes hard. I know, she says. I know. You are starving. But the clay will never fill you up.