Synopsis

Tempestad Ramirez tells the story of how she became recruited by the Narcos at the age of fourteen and became a member of a group of hired assassins made out entirely of children.

The first time I took someone’s life I did so with a whisper.

I was just a child back then. Mamma owned a small pocket-size revolver that she had bought at a discount from a gypsy who was passing through one rainy afternoon, but I wasn’t allowed anywhere near it; therefore, all I had at my disposal to rid the world from the man who had tormented me to the very core of my bones, who had bent our family’s will so far back we were about to snap, was my tongue and the stashed knowledge that he liked to wear women’s underwear.

I was born in the underbelly of “Hell.” Shooting out of Mamma’s womb, I landed all wet and slimy on a skimpy, urine-stained mattress that Mamma had refused to throw away because it had brought her luck by welcoming my three brothers into the world before me. “Hell” is what we called the pooped, threadbare, shattered, about-to-collapse ring of crooked houses built at the top of a hill upon scaffoldings and frameworks that shook like cobwebs at the mercy of the wind. “Hell” was the dilapidated neighborhood nestled in the outback’s of a huge metropolis located on the northern tip of the country where my mother’s family had lived for generations.

Legend has it, or at least one of the many legends my brothers used to spin into existence through the unified buzzing of their mouths, that I was born in the middle of a thunderstorm, and that is why Mamma had given me the name Tempestad Ramirez.

Mamma was a woman of many dichotomies, with perpetual shadows swinging under her eyes, which outlined a network of fine wrinkles I liked to trace with my fingertip the same way I had seen an explorer on TV trace the tributaries of a river drawn messily on a map. Mamma wanted the best for us. I am convinced that her heart was a labyrinth of rooms crowded with unabridged affection. She pinched our cheeks and peppered our lice-ridden skulls with kisses every chance she got. That didn’t mean that she wasn’t rigid and merciless in her parenting style when she needed to. When she was around, she wandered through our small, ramshackle house like rolling fog, silently and stealthily dissolving into tendrils of mist that spread through the hallways and fitted in through the locks of the doors. Imperceptible, she watched and studied and judged our every move, making sure that my brothers and I weren’t plotting any shenanigans behind her back.

Mamma was as unwavering as the hardest of steels when it came to administering her millenarian punishments when we disobeyed her or misbehaved, employing various tactics that ranged from whipping us red on the buttocks with a bamboo stick to flattening our hand on top of the burning stove until the lines on our palms melted away. Mamma went to extreme lengths to ensure that we understood the error of our ways because she didn’t want us to remain trapped in “Hell” for the rest of our lives like her and the other inconsequential souls that bounced about like blinded ghouls through the twisting corridors of the neighboring homes.

Mamma told me that when she was a little girl, all she wanted for her birthday was a doll with movable limbs, exactly like the ones she saw the light-skinned girls at the bus stop hugging on her way to school, but because Mamma and her mamma were flat-ass broke, all Mamma got every birthday were stiff, discarded dolls made of corrosive plastic that could not bend even a finger and that Grandma rescued from the dump. Mamma hated these dolls, with their frilly, polka-dot dresses stained with a constellation of unknown fluids, with their lifeless opal-black eyes, and their bald heads with copper wires sticking out. Mamma came up with fantastic ways to torture these dolls. She would pile up logs of wood and burn them at the stake like witches. Mamma would also wedge them under the wheels of a tractor and wait hours hidden under copious shadows for the driver to spur the engine to life. She loved the delicious crunching sound produced by the doll’s plastic body as it was being crushed under the wheels.

Mamma said she was happy she had never gotten one of those movable dolls she had coveted so desperately. She said all that waiting had paid off. “How did it pay off?” I asked her. “I was rewarded with a real-life doll I can pamper and hug and love and tickle under all her flexible limbs.” “Where is that doll, Mamma?” “I am looking at her, dummy.”

Mamma worked two jobs. That is why she wasn’t around much, or at all, for that matter. During the day she labored in the kitchen of a restaurant, washing the dishes and mopping the floors, carrying boxes and bustling in and out of the pantry until the burning in her spine was overwhelming, and she felt as if she had been skewered between the vertebrae. Mamma said she had been reprimanded several times by the manager for taking countless cigarette breaks, but she said that sitting on the curve of the alleyway puffing away at a smoke was the only remedy for the pain and the tiredness that dug into the very center of her skeleton.

Mamma wasn’t lazy. Don’t get me wrong. She had to take care of herself so she wouldn’t get fired from her second job, which paid her more but required that her back and the rest of her limbs were as limber and pliant as clay. Mamma was an exotic dancer by night. The bar where Mamma worked was an encampment through which riders and truckers and field workers could stop by on their way to the North to rest their muscles and empty their bowels and quench the thirst of their loins. That is how Mamma explained it to me and my brothers one night. I couldn't make out exactly what she meant by “quench the thirst of their loins.” The words and their meaning never registered in my brain and instead lingered in the air like hieroglyphics I thought I could poke. When Mamma first started working the rounds at the bar, her responsibilities were limited to carrying trays laden with drinks and snacks for the patrons. The fluctuating beams of rainbow lights coming from the stage blinded her and made her stumble against robust cowboys and cartel members who smelled of Aqua Net and perspiration, who fondled her and grinned as Mamma apologized for her clumsiness. She completed her shifts in silence, treading through the gamboling crowd with a fixed smile on her lips, and her eyes guarded and cast to the floor.

But the years fluttered by, and Mamma became more confident. She outgrew her inherent shyness and sculpted her body by doing home aerobics. She had to spy on the neighbor from our window and mimic all her movements because we didn’t own a TV. She was soon removed from her role as a waitress and was jostled to the stage to perform and dance. Mamma’s body was more malleable than some of the other girls’ bodies, and she learned quickly how to maneuver the pole and sway her hips rhythmically to the ranchera music, peeling off her clothes at times raunchily, and at times daintily, focusing her gaze on the disco ball twirling above her head as to not crash against the lascivious eyeballs whirling below her feet.

After I was born, Mamma took the advice from her colleagues and drank bubbling concoctions to stop any kind of life from growing in her womb again. She also learned from them that downing as many beers as the men pitched in made the job easier to bear. She never drank at home, but every morning I would find her yawning and nursing a headache with scalding tea and crushed aspirins. She blabbered incoherencies and drooled over my fried eggs until she dunked her head into a bucket of freezing water like some sort of aquatic ostrich. Then, with her hair dripping and her jaw chattering but no longer zombified, Mamma continued with her daily routine. Mamma said she hated drinking at the bar, but the intoxicating daze of the alcohol helped her dance better, it sustained her through the intransigence of the night, and if truth be told, after guzzling about ten beers, Mamma fell under an ethereal spell that transformed her into the shiniest star illuminating that wretched place.

I know nothing of the man who put me in Mamma's belly, except that he was a member of the cartel and an asshole and very bad at his job, and the sum of all these qualities led to his demise. He was killed by his boss after he was caught red-handed snitching to another criminal group about the whereabouts of the bodegas where one of the cartels squirreled the drugs away. I was three when he was gunned down and strung up to a bridge in the middle of a busy intersection. My brothers liked to boast about our father’s downfall to the other kids in the neighborhood, dyeing the story with unreal and mythological pigments.

Everyone in “Hell” had lost at least one family member to one of the cartels battling control of the land. Everyone liked to brag about how their relatives had been pumped full of lead or roasted in acid. It wasn’t easy to top the sanguinary stories that kept cropping up every week among the humming clicks of recently orphaned boys and girls championing for the title of coolest story and most savage way to lose your parents. It was a matter of pride to have a family member felled by one of the cartels among your bloodline. If you lived in our slums but everyone in your family was still alive or had no dealings with the Narcos, then it was most likely that you were an outcast who got beaten up at every opportunity by the other kids. Your reputation could skyrocket or plummet depending on how garishly your father or your mother or your uncle or your grandmother had been dispatched to the otherworld by the Narcos. There was even a system of points under which your popularity and rank among the groups of children could be measured. If a member of your immediate family was murdered, meaning your father or mother or siblings, you got ten points. If a cousin or an aunt or a relative who didn’t live in the same house as you was the one who was killed, then you only earned five points.

Then there was the matter of the killing itself. Decapitation or dismemberment was the most valuable kind of death in the point system, followed by being burnt alive inside a barrel or being dissolved in acid. “The Necklace of Blood,” which was what people in the neighborhood called having your neck sliced from ear to ear with a butcher knife, was up there in the charts, too. The lamest of all executions, which granted the least number of points, was being shot between the eyes or on the back of the skull.

Finally, the last category to take into consideration in the point system was the location where the body of your family member was dumped. In “Hell,” cadavers were disposed of under the cover of darkness left and right. Some of these corpses were found inside the trunks of abandoned cars when the reek of putrid flesh and stagnant blood became unbearable. Others were pulled out of swamps and quagmires after someone spotted a gnarled hand sticking out from underneath the brambles. When bodies were disposed of in this fashion, it usually meant that punishment had been inflicted as retribution for petty and unimportant squabbles between cartel members. But the bodies that were dropped in the middle of a traffic-congested street to the shock of the unfortunate passersby, or tossed from a high bridge with a noose around their neck and a piece of cardboard clipped to their chest with the name of the criminal group or drug lord responsible for the atrocity doodled on it, well, that was a whole different story. Whatever betrayal these men or women had committed against one of the cartels had been taken as a personal offense by its leaders, hence the need to strike fear into the heart of the general population by exposing the consequences of their actions.

Our father had been shot on the forehead. His hands and feet were chopped off, and his wiener unscrewed from between his legs and stuffed into his mouth. That is what the Cartel did to all the snitches. Unless you were a woman. Then they would shove one of your severed boobs down your throat. So, as you can see, we were at the very top of the social ladder. My brothers were regarded in such high esteem among the other boys that they would organize tour guides around the famous spots where the Cartel had hung or dumped or forsaken the corpses of their enemies. They invented backstories for the men who had been found at the bottom of the rundown well covered in moss, adding untruthful, gory details such as that they had been found without teeth and Cat Eye marbles for eyes. They rehearsed and learned by memory the story of the woman whose body had been disintegrated in the bathtub of the derelict blue house at the top of the hill, but whose head it was said had been preserved in a jar of conserves because the drug lord who had ordered her execution wanted to keep something from her as a cherished memento.

My brothers were great at whipping up fibs about people they had never known in life, but when they got to the bridge where our father had been strung up, they were always overtaken by the fantastical giddiness that comes with being related to someone famous, and they tripped on their words and faltered when committing to their rehearsed speech.

Mamma had had an array of boyfriends after Father gave up the ghost. Most of these boyfriends Mamma met at the bar where she danced. They always promised to make an honorable woman out of her, but in clockwork synchronicity, as soon as she took them in, they stripped themselves of the layers that had originally charmed her and revealed themselves to be scumbags with air in their heads too weak and meek to handle Mamma's rebellious streak. They would lash out at her in flares of sadistic rage to cover up the swarm of insecurities that spilled over their hearts when they found out Mamma was untamable and could not be reduced to the role of a housewife. Our home was filled with the echo of these men’s insults. And, yes, they would strike me. Yes, they would verbally abuse me. But they were always out the door in the snap of a finger after Mamma deemed it was time to resort to her trustworthy technique of drugging them out of their minds. She would spike their morning coffee with a roofie, and proceeded to wrap them up like a human burrito with a sheet or a carpet or a drape or whatever billowy fabric was left in our house. Mamma would then ask one of her girlfriends to drive her to one of the surrounding hills where she pushed the male nuisance down the slope and the unconscious bastard rolled over and over until the darkness at the bottom of the pit swallowed him whole, and we never heard of the brute again.

One of them, who we thought for a moment was immortal because he kept on resurrecting and crawling out of the gaping blackness at the bottom of the hill, did serious harm to my face at a barbeque once. The music was blaring loud and people were dancing. The air was thick with cigarette smoke and the scent of grilled meat. The drinks were flowing and the mood was festive. Suddenly, this man, Mamma’s boyfriend at the time, sidled up to me, and pinched me in the butt. I turned around and kicked him in the shin. His gaze held me in place for a moment, as if he couldn’t believe what I had just done. It happened in a flash, and even now, in my memory, I see it all in broken bits. He smacked me on the left side of my face with his right hand. There was a collective gasp. Mamma said he was a bit of a pansy because he liked to wear heavy, glittering rings, but she had kept him around despite these rumors because he had a huge sausage and was the only man who knew how to use his tongue. I found this quality odd because I never considered him much of a talker. Anyway, his rings made the slap even more painful. I felt his rings scraping against the skin of my cheek and I winced and even felt a little dizzy. My eyes were misty and my head felt dulled. One of those heavy rings had a jutting stone, and the stone tore a gash on my cheek. The gash stretched down my face for about half an inch. It bled profusely, and blood trickled down until there was a red, watery bouquet that dripped-dripped on my blouse. It took about a week of icing it for the swelling to go down and for my cheek to heal.

After that incident, Mamma roofied her ring-cladded boyfriend and pushed him down the slope, but like I mentioned before, he kept coming back. That was when Mamma got herself a gun from a gypsy she stumbled upon on her way to the bar. The next time we spotted that man sauntering the twisting path curving up to our house after Mamma’s third attempt at disposing of him, she fired two warning shots at his feet. He leapt like a scared frog but threatened to dash up to our door and beat us to a pulp. The third bullet Mamma fired blasted his left toe. He scampered away and he finally decided to never come back.

Despite being proud of the vast degrees of independence with which she ruled and maneuvered her own life, Mamma was one of those irrefutable dreamers who believed fervently in the breed of love that only exists in telenovelas and that makes a person go woozy in the head. Therefore, whenever the parasite of love burrowed unexpectedly into the folds of her brain, Mamma willingly lowered her defenses, and every trace of logic flickering in her skull was snuffed out.

When I was eleven, we moved to Papa Fresco’s rickety house. Papa Fresco had enchanted Mamma with his puma eyes and six-pack abs. He earned the nickname Fresco because it was said that he had engendered at least a dozen children and his acrobatics in bed were the stuff of legends. He strutted around the neighborhood as if his feet were bars of soap, feeling himself too fresh for any lady who didn’t fit the standards of his tastes. Papa Fresco had visited Mamma every night at the bar to watch her dance, and in some inexplicable manner that neither my brothers nor I were ever able to comprehend, Papa Fresco penetrated Mamma’s chest and tunneled his way into her heart like a fulminating stroke. He would ultimately wrung her pumping organ like a mop until all her dignity had been squeezed out of its tangle of ventricles, but we didn’t know that yet. She woke us up one night, announced that she was packing our bags, and we should be ecstatic because we were about to start living in a better house with a man that would love us like a father.

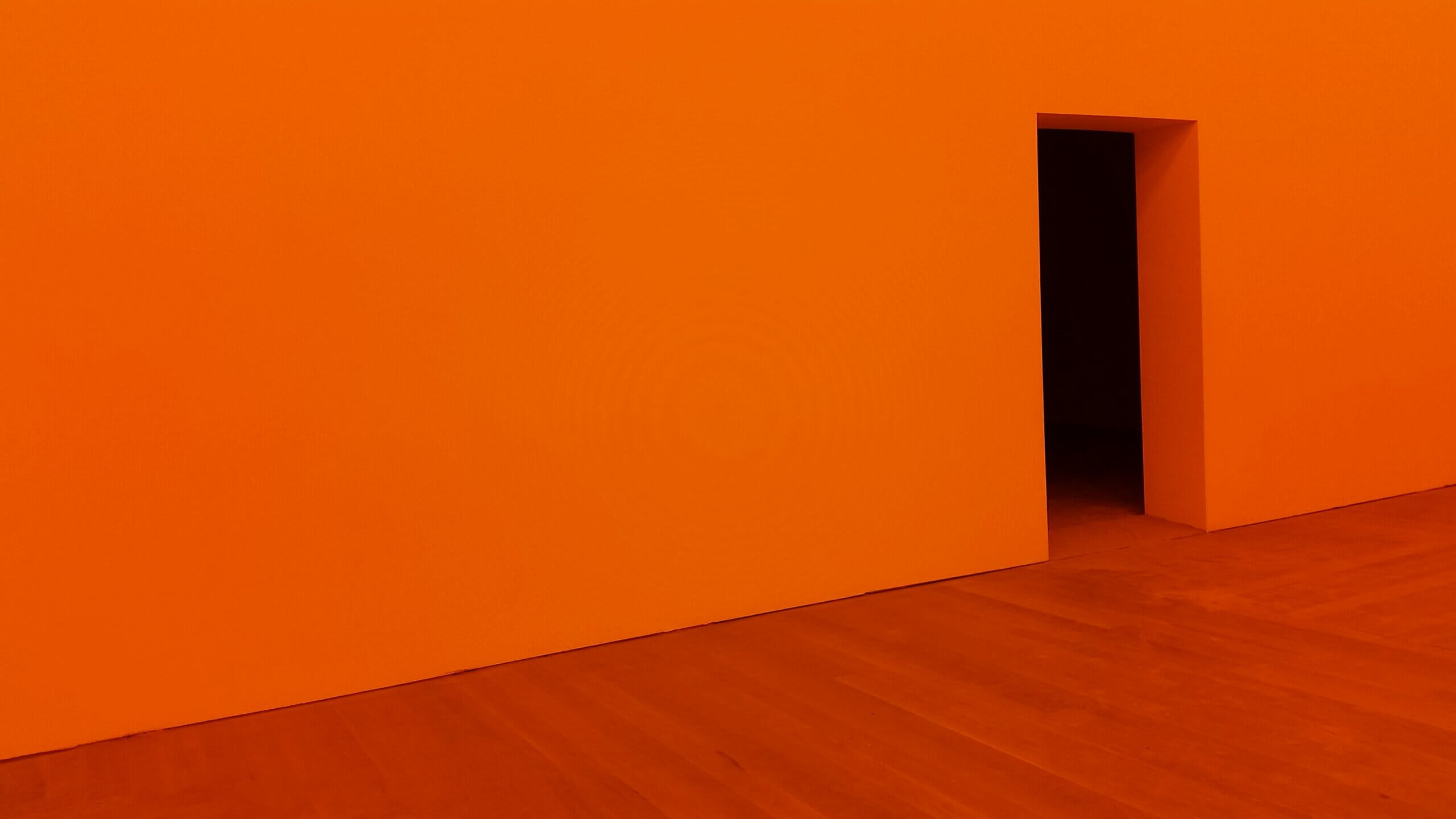

Papa Fresco’s house was not better than our house. It was a squatted cement box with an orange portico that stood in a more destitute sector of “Hell.” The house was bigger than ours, and there was an aura of sophisticated mystery perfusing it because it was shrouded by umbrageous trees and ringed by hills that wore scarfs of fog. But who cared about all that when we were scared stiff of its owner and all the ghosts that inhabited it? Papa Fresco never loved us like a father. I navigated through the last vestiges of my childhood in his house burdened by a more cumbersome poverty than the one I had experienced living in a crammed room with Mamma and my three brothers.

There was an animal in Papa Fresco’s belly, and when he drank, it moved through his blood until it reached his skull and bit the lick of his brain, rendering him soulless and brutal. I learned early on, that if I wanted to make it out of that new house alive and in one piece, I needed to be as slippery as a shadow as to not get caught in the middle of one of Papa Fresco’s fluctuating and altering foul moods. After we moved into Papa Fresco’s house, every portion of ourselves, every affixed atom of our being, became his property. When he was around, we drifted through the house with our lips pursed, taking ninja-quiet footsteps, just so that his rage and fascist personality wouldn’t flare up and he wouldn’t have an excuse to go rampant on us and barrel his way to where Mamma was standing to knock the living lights out of her for no apparent reason other than she was the woman who had chosen to love him and now she had to pay for it.