September 2016

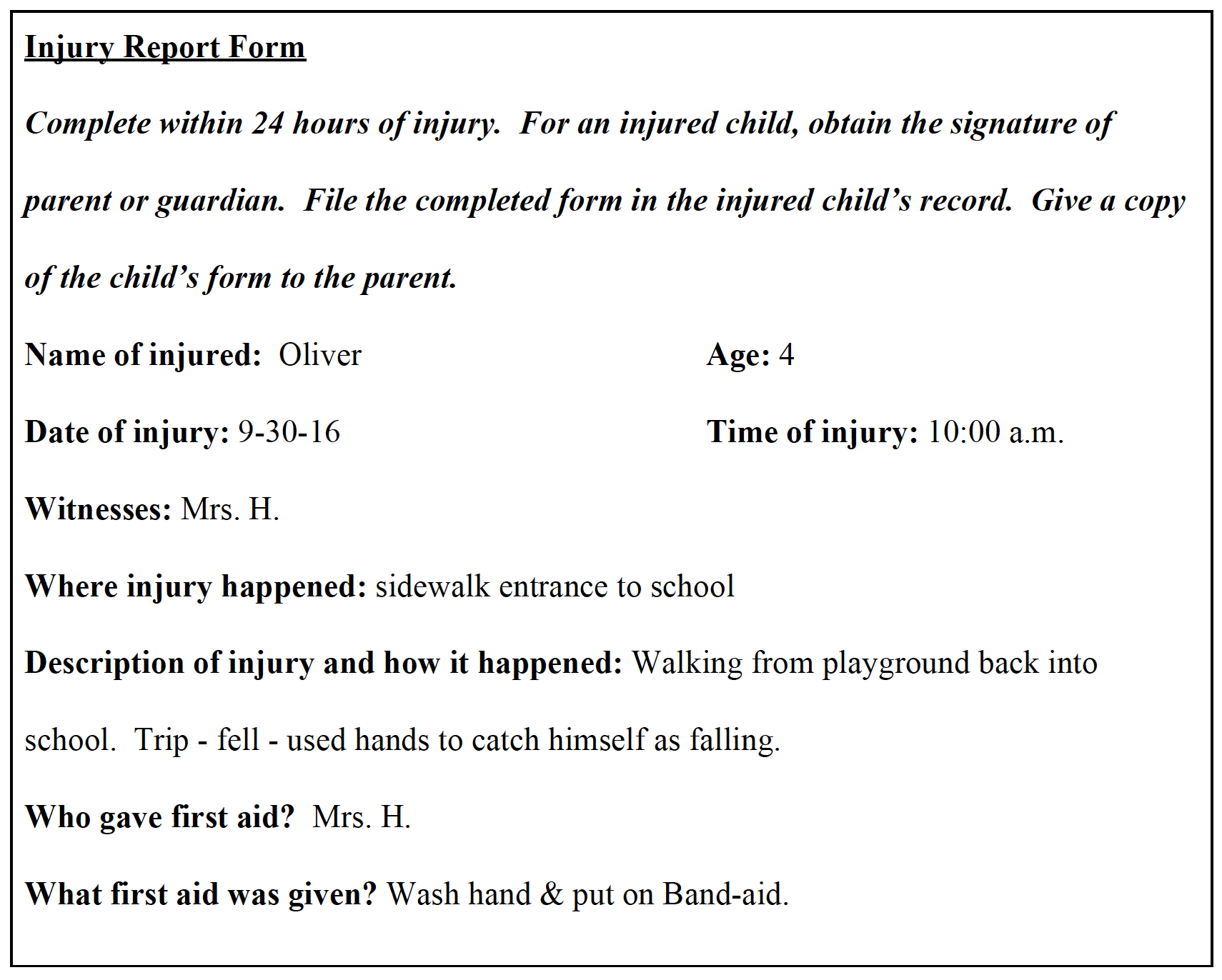

Folded neatly in the front pocket of my older son’s preschool bag is an injury report form.

And my own heart trips, unable to catch itself from falling.

Not in concern for his scraped hand. Not in surprise that his teachers even filled out and sent a form for an injury that, when I check, is not evident. Not in gratitude that they cared for my son, though I am grateful. Grateful every day that I have complete confidence in his caregivers.

Grateful that since we sent him out into his first world beyond our home, there have been many other loving arms to catch his falls.

No, my own injury report form would hold this realization: I’m not ready for the escalating damages.

For me, motherhood was a choice and a challenge. Something that, for at least a year, I didn’t know I’d ever experience. And, when my oldest was born, I couldn’t hold him at first. Anyone can rationalize my reaction by listing the details of his birth story: Thirty hours without food or sleep; a completely new, physically and emotionally taxing experience; pain medication shaking my system. But my divide was more than that. Two false starts, two years of angst, miscarriages, surgery, and exhaustion had drained my emotional well. Could I handle his vulnerability and mine?

My fear had deeper roots as well: As a high school teacher, I know brutally well what can be at stake. Almost every day, I witness some kind of “injury,” some physical, some emotional, some annoying, some serious. Most of the time, my own report forms are phone calls or emails to students, parents, and guidance counselors:

“I just wanted to let you know that I had to kick Jacob out of class today because he kept yelling to the whole class that he’s bringing Jello shots to the goodbye potluck for our student teacher tomorrow. I know he’s having a tough time right now...”

“Hannah wrote in her memoir about wanting to jump out a window and kill herself…”

“Sam jumped Alec in the bathroom during class today…”

I’m not ready to receive those emails myself someday.

October 2016

Before our last class of the day, Derrick stands in front of my desk and asks if I have a minute. I’m in teacher mode, my eyes on the computer, fingers flying through an email: “Okay, just give me a minute... so I can give you my full attention...” I say, my standard response for navigating the ever-changing classroom demands. I hit send, look up, and instantly realize my usual response was to an unusual request. His nervous posture betrays him: low voice, shifting stance. I try the reverse, masking my own surprise with a calm approach:

- start class (“Hey everyone, pull out your books and read…”)

- walk him out of the classroom

- move down the hall out of earshot

Oh, and 4: Stay casual, even with alarm bells ringing in my head.

“What’s going on, Derrick?”

“I just wanted you to know that I got a concussion trying to commit suicide this weekend.”

We are walking side by side down the hall, but I turn and look at him. His face relaxed, composed. With this tone, Derrick could have easily said, “I just wanted you to know that I got accepted into college this weekend.” I had edited his scholarship application letter, just five days ago, reading his words: “I am looking forward to college helping me reach my future goals... the small community feel of your college appeals to me... I’ve learned dedication through sports...”

This was also the same student who, just five months ago, for a group final film assignment in my class, put on a helmet and had himself duct-taped to a tree for their own MTV Jackass-style parody show. I had watched their rough cuts, horrified as the other members of his group shot bottle rockets at him, them merely laughing when Derrick’s dad had to strip him from the tree because one hit Derrick in the leg and burned a hole through his pants.

Now I struggle to process the words he stated, just five seconds ago.

Derrick and I had been in previous vulnerable territory, only that time, it was him helping me process. Two years ago, as a sophomore, he was a student in a class that almost caused me to quit teaching, each day a struggle to keep up with their ridiculous expectations, their need for validation:

“Your rubrics are setting us up to fail.”

“My brother goes to the University of Iowa, and he’s never heard of a ‘C’ meeting minimum requirements.”

“If we do everything you ask us to do, why don’t we get an A?”

All of this immaturity culminating one unimaginable day when a student took a shit — on a dare — in my classroom. A sixteen-year-old’s, purposeful turd in the open corner of my classroom carpet. I was also seven months pregnant, just trying to hold on for Thanksgiving Break the next day. Derrick was the one who clued me in on the mess, looking over at the waste, and saying, “What. is. that?”

Now, two years later, I have Derrick for two senior-level classes, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. And now we’re muddling through his dark moment, not mine. He continues by explaining, “That’s why I wasn’t here this morning for first hour. We were at the hospital working this out.”

Somehow I finish the conversation with him, erring on the side of sincerity and concern, though it’s still blurry and stilted. Our school district had a heartbreaking outbreak of suicides a few years before, so even though I’ve been trained for this moment, I don’t feel prepared. Nobody teaches you what to do when a student cruelly drops his pants because you were focused on two other students for a minute. Nobody teaches you how to stay calm when a student admits he tried to kill himself. Nobody teaches you that being an adult and a parent is to live with constant, disgusting uncertainty.

When I was little, before cell phones or email, our injury reports usually took the form of little legs. If someone got hurt—like the time I turned too fast on my bike and fell, scraping my face on the driveway—we sent a messenger: sweaty kid’s little feet slapping the sidewalk as fast as they could go, up to the doorbell, then the smack of the screen door as a parent would sprint back to the scene of the injury to assess the damage.

Now that I’m on the other side, I live in constant anticipation of the injury messenger. After my son was born, my fear compounded, escalating into irrationality. None of the parenting books teach you how to handle your deepest, darkest fears when you are alone, holding a baby in the middle of the night. None of the parenting books teach you how to handle your sanity when your baby screams at you for hours and all you can do is make sure he’s safe, put him down, and walk away. None of the parenting books teach you how to walk away from your own baby for a few minutes because you think you will hurt someone you love if you don’t. None of the parenting books teach what to do when you are forced to imagine your son’s face in the smart, capable, witty teenager looking at you and saying he tried to end his whole existence this past weekend.

Six months after I became a parent, there was an unimaginable shooting in Connecticut, when a young adult man forced his way into an elementary school, killing twenty children and six adults. I heard the news from a sweet girl in 8th period, our last class of the day: “Did you hear about the shooting at an elementary school?” My heart tripped, and I tried to understand what she was telling me, without overwhelming her with questions. Details unfolded on the news, and we all waited, quiet and hollow, for the clock to tick to 2:50 p.m., when we could shuffle out the door. At home later, during my own next shift as a parent, I sobbed at my husband, clutching my innocent baby, thick tears baptizing him into a world that would allow this to happen: “What if that were Oliver?! What if that were him in the elementary school today?!”

helphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelphelp

The fear compounded, escalating into constant waves of panic. Days churning with new worries, avoiding the news to avoid triggering my fears of what could happen. Nights of trying everything to soothe this screaming baby whom I couldn’t avoid but who triggered my own feelings of worthlessness. I chose this, but I can’t do this. I knew I needed help when one evening I didn’t see the point anymore. Every day was the same: screaming baby, fear, hopelessness. I couldn’t see beyond each day, and I didn’t want to do anything I used to love: read, exercise, write. I took a deep breath and called our Employee Assistance Program, and within a few days, I was sobbing on a therapist’s couch, facing a lovely woman who could be my grandma’s age, her softly leading me from the shadows toward the sun.

The fear finally had a name: postpartum depression. My own report.

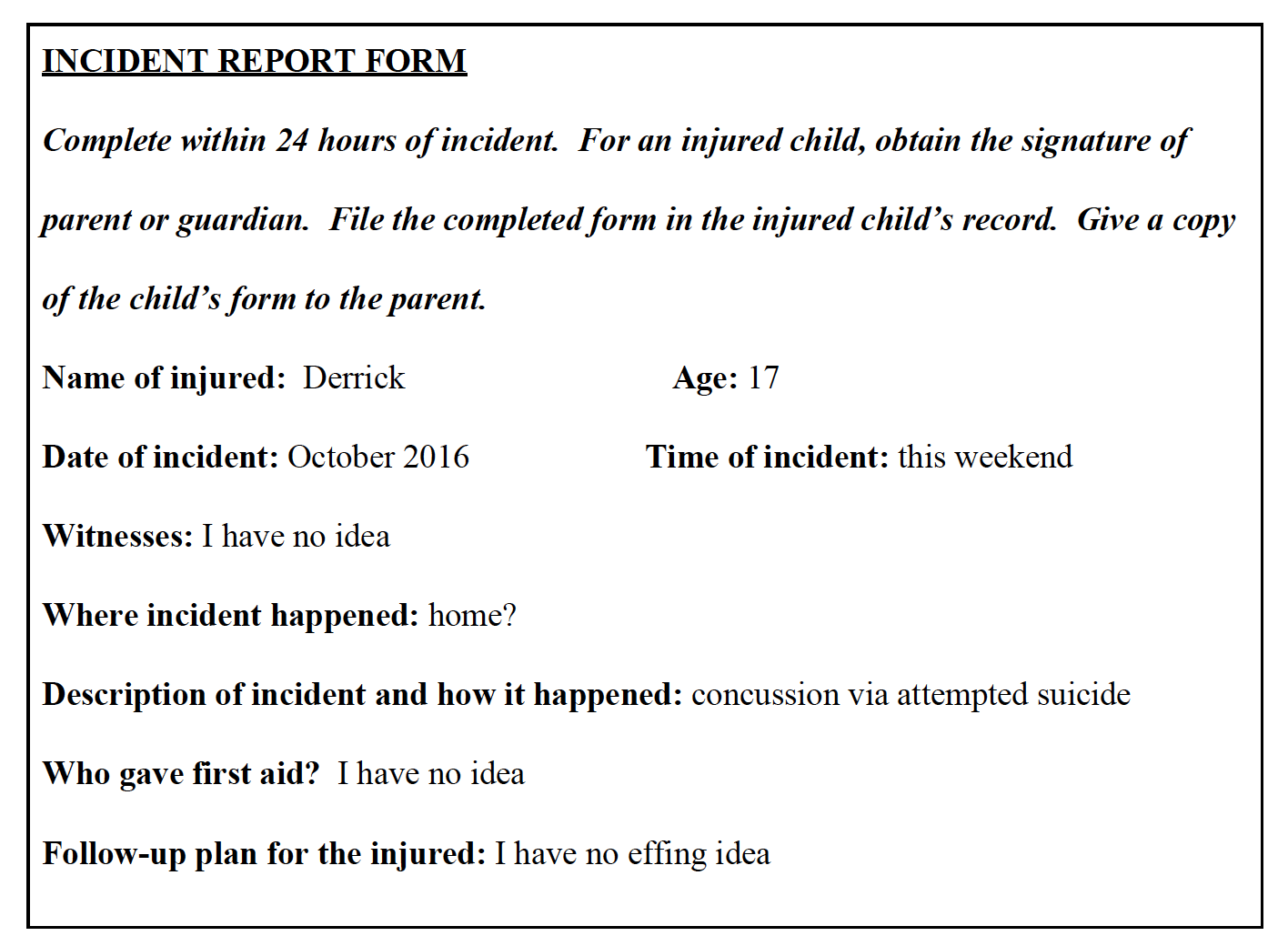

In the few years since then, I still struggle to understand other people’s triggers and my own. With Derrick standing in front of me, admitting what happened, admitting what could have been much worse, what is my form of report now? My son’s injury report form flashes through my head, only this time I imagine today’s scenario:

Derrick and I walk back to the classroom. At least for now, he is in my room, and he is safe. I fire off a quick email to his counselor:

10/14/16

2:05 p.m.

From: kg@school.com

To: school.counselor@school.com

Subject: URGENT: DW!

Um, I just had a strange conversation with Derrick at the beginning of class today. He said he got a concussion trying to commit suicide this weekend… do you know anything about this????

10/14/16

2:06 p.m.

From: school.counselor@school.com

To: kg@school.com

Subject: Out-of-office reply

I am out of the office today with all the counselors for training. If you need immediate assistance, please contact our Guidance Office Administrator.

10/14/16

2:09 p.m.

From: school.counselor@school.com

To: kg@school.com

Subject: Re: URGENT: DW!

I had no idea! We are off-site for training. I will call his Mom and Dad.

Slowly, the counselor and I piece together details. He finds out from Derrick ’s parents that, though the story is true, they still sent him to school, with no prior notification about what had happened. I fumble through teaching the last twenty minutes of the school day. Meanwhile, my mind compiles lists:

Things I don’t want to relive

Junior high bullies

Junior high. All of it.

Disappointment

Heartbreak

Betrayal

Suffering

Uncertainty

Things I fear

Everything

School shootings

Abductions

Childhood cancer

Gun violence

Suicide

Teenage impulsivity

Now I worry there are too many injury reports to reconcile.

November 2016

I look at the student desk nearest mine. Gavin is here but sitting with his head down on his arms. My usual tactic — to lightly joke with a sleeping student, “Are you alive?”— won’t work. This is more than “I stayed up too late” sleep. I get the rest of the class started, then tap Gavin on the shoulder and, when he looks up, nod my head in the direction of the door.

Once we are outside the classroom, I ask, “How are you? You look like you’re having a rough day.” I know that Gavin’s rough days are worse than for the rest of us — his mom notified me that his repeated absences are due to a punishing bout of depression. Now that he is up and facing me, I search his face for recognition. His eyes are half open, as though heavy with the exhaustion of the thousand lives he can’t bear to live. He sighs and responds — slow, steady, weighted: “I. just. want. to. die.”

In the second it takes me to measure his words, I know.

I know this is not a drill.

I know I have to—I want to—take his words seriously.

I know that as a mom of two boys, I am haunted by our struggling male students, our rising emotional injury reports.

Because of this, I don’t remember what I said to him. But I move forward, contacting Gavin’s counselor immediately—all while imagining my preschooler’s sweet face and wondering: How much longer until I beg for the days when pain and injuries can be fixed with some soap, a bandage, and a little time?