Dear Suzanne,

How delighted I am, after all these years, to have reconnected. Thanks to you, that is. I—Luddite that I am—have only been vaguely aware of social media, consigning it, until now, to that circle of hell designated for all the mindless chatter that masquerades as communication these days.

The world has changed much since our happy days in Cambridge. What fond memories I have of our long afternoons, lingering over coffee or something stronger, exploring together the pleasures of Proust, the surprise of Cesare Pavese. So news of your stellar career doesn’t surprise me. As for me, I didn’t finish—but you could have predicted that. In the end I succumbed to my relentless wanderlust. I carried my nascent tome with me as I traveled, but the world was too much with me, yet I kept it in case one day it would call to me again.

To reassure you, yes, I am safe here in New Orleans. I was luckier than many, although not without my share of travails. Which I will get to. We have much to catch up on! Let me start with when we parted, and bring you up to date.

My first destination, Amsterdam, with its kaleidoscope of mind-altering ministrations, did not disappoint. Always nimble in the art of self-preservation, I supported myself teaching English or doing translation work, existing in the semi-respectable world of the adjunct academic. I enjoyed freedom from all those tiresome meetings, and spent my free time following whatever piqued my interest. I will let you use your imagination—you who know my predilections for the demimonde—and I assure you, I had a fine time of it.

Having exhausted, finally, the treasures of the Mauritshuis—you know my love of Vermeer, of Rembrandt—and the pleasures of the streets, I found myself restless again, so leaving the dour Dutch—who for all their drugs are relentlessly bourgeois—and seeking warmer climes, I found myself in France. I switched my allegiance to wine, about which I became fascinated, taking on the world of wine connoisseurship as a vast continent to be conquered. I saw this as a step towards maturity, and as I say this I can see the ironic twinkle in your eye. Don’t laugh. I found Aix to be a comfortable fit, full of universities and more importantly, outdoor cafes where long-legged students and hoary professors whiled away the hours over coffee or wine. I found a job easily, and set about enjoying my education. My French quickly improved, as did my palate—France is a very oral country. I enjoyed the land of Cezanne, of Zola, feeling myself at last in the place I was meant to be.

But then, in the midst of my tutelage, I met a young woman from Rome. We quickly engaged in a heated debate about French versus Italian grapes, and to prove her point, she introduced me to a lovely Montepulciano. As we conversed, I found myself entranced by her softly caressing syllables, not to mention her bountiful olive breasts. That night I had the revelation that French women were entirely too thin and their language too bright and witty. An appetite for earthier pleasures surged to the fore, not only for the terracotta darling across the table from me, but for pasta, for generous portions of boar stew, for tiramisu, tortoni, zabaglione. Say those words and you can almost taste the unabashed sensuality of the Italians.

Lorenza urged me to come to Rome. Although vacationing in France, she clearly disdained the disdainful French. “Oh,” she said, “Marcus, you will love Rome! It is so alive, the history, the art, the people—we are like fire!” And so I bid adieu to my ironic French friends and headed to Rome.

Lorenza and I soon parted company—for all her fire, she was a devout and chaste Catholic, alas. But I didn’t regret having moved. I quickly found a job teaching English to businessmen. Not the most stimulating environment, but it was easy and provided me time. I enjoyed my unencumbered visits to the Coliseum—I almost expected to see the ghost of Nathanial Hawthorne sauntering about, notebook in hand—and the Vatican collections.

Each day, I reveled in new discoveries. The Sistine Chapel is as glorious as its reputation would have it. I was particularly taken with the Last Judgment, the drama of the awakening dead ascending and recovering their bodies, while the damned were taken by Charon, a frightening figure covered with the coils of a serpent, and his devils to Minos. Despite its majesty, the fresco made me glad I was not a believer, that I hadn’t grown up with such scalding images of hell.

I was intrigued mostly, though, by the musty Capuchin Crypt. Somehow, I had never heard of it, although I am sure that, scholar that you are, have. If you haven’t been there, let me describe it to you. Imagine descending into this tiny, dim space smelling of ancient dust. You enter small connected chapels lined with the bones of over 4000 monks who died between 1588 and 1870. The six chapels contain arrangements of skulls, of pelvis, thigh or leg bones. So odd, this division of the human skeleton into categories of bones. Was it an artistic decision, or was it meant to suggest the dismembering triumph of death over the singular life? If you forget that you are looking at human bones, the effect can be quite lovely. I liked, for instance, the delicate chandelier made of sacral bones, and the intricate floral designs of toe and finger bones. You can imagine the monks’ candle light flickering eerily across the skulls arranged in pyramids and arches, all those eye sockets staring fixedly. Evidently the monks came here to pray and be reminded of their mortality.

In the final chamber are three intact skeletons: the center skeleton, enclosed in an oval, holds a scythe in its right hand, while its left hand holds the scales. A placard in five languages declares "What you are now we used to be, what we are now you will be." How strange that I, avowed hedonist that I am, would find the message strangely confirming, certainly not its intended aim. Yet it strengthened me in my conviction to “seize the day.” I was only too glad to leave the musty place for the surface, where I sought out my favorite restaurant and spared no expense.

I saved enough money—for all my love of pleasure, I don’t accumulate things—to quit my job and travel to Sicily, then Tuscany. Though Florence was overrun by tourists, one can’t help but enjoy it. Tuscany is like a buxom grandmother—gentle, undemanding, always urging more food on one. The landscape is gentle as well, open and sunny. I had as my companions the voices of James, Tolstoy, and Forster. What a luxury to travel with those voices, glancing out the train windows at the same cypress-lined landscape they described!

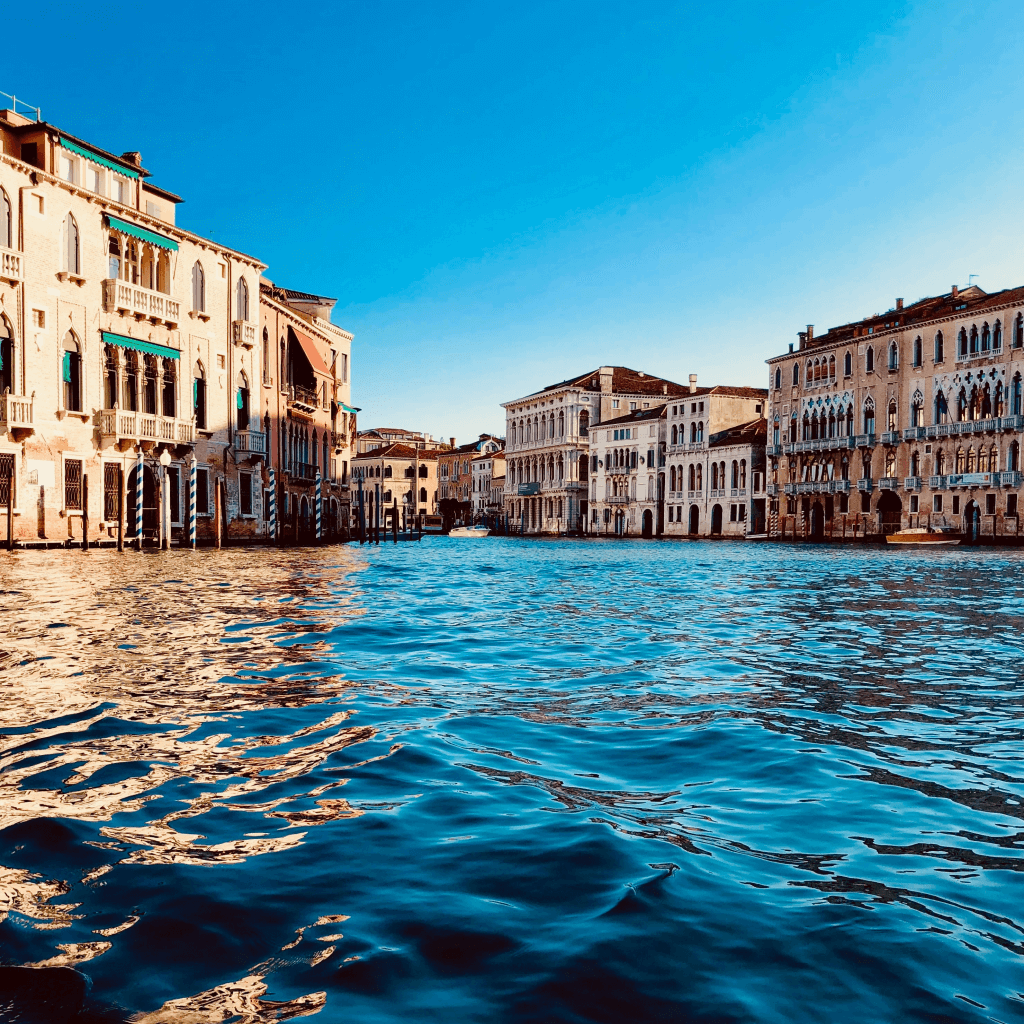

I finally headed north, for Venice. Ah, Venice. Next to Venice, Florence seemed too easy. Venice does not open her floury arms to you. No, she is that woman of a certain age, still enticing, but world-weary. The city is sinking in all ways, physically, economically, but it only makes her more enticing, the way a former beauty’s ravaged face can haunt your dreams. The vendors there disdain tourists, regarding the eager Americans exclaiming at their booths as one would a horde of ill-behaved puppies. So I pressed back into the residential squares, away from the tourist trash. Finding the proud Venetians as fascinating as the city, I decided to stay and see the city in all its seasons, acqua alta notwithstanding. If ever a city could contain enough mystery to hold me, it was this one. It was as if I had fallen in love.

The city did have many surprises in store for me, one in particular which I will get to. I was able to secure a position at the Peggy Guggenheim, writing press releases and working in PR. I loved working there, and gained companions through it—an American couple I found amusing, the Walters, who had more money than they knew what to do with, and were avid to buy their way into culture. I gave them an entrée into the true bohemian class, and they footed quite a few excursions for me.

I frequented a marvelous trattoria in my neighborhood. I had grown to prefer Venetian food over Tuscan—my favorite, squid in ink over creamy polenta, which is a visual as well as culinary delight, the black salty ink and chewy squid a perfect foil for the creamy golden polenta. In Venice there was a refinement to the food, yet it retained a robust earthiness. I still miss it.

It was at my trattoria that I met Clothilde. Ah, I can hear you say, it always comes down to a woman.

She was beautiful, but not in a conventional way. I noticed her sitting there, tall, elegant, with her dark hair pulled back severely from her oval face. There was something oddly old-fashioned about her dark, simple dress and her understated scarf, something arresting about her bearing. She had an olive complexion, and I assumed she was from the Middle East or North Africa and so was surprised to hear her speaking English with the waitress, her accent clearly American, although hard to place. As I ate my first course, I found myself glancing at her profile framed by the lace-curtained windows. There was a stillness to her, not of emptiness, but of a kind of concentration. It was as if she was surrounded by an impenetrable solitude, which I took as a personal challenge.

I felt oddly at sea, as if I might fail to connect with her. I summoned my wits, and hoping to strike just the right note, genteel yet casual, I asked her if she was indeed an American. She seemed, as is often the case in these situations, relieved to have someone from the States to talk with, and confessed to being tired out from her efforts to speak Italian all day.

The trattoria was small enough to allow us to converse comfortably from our respective tables. The conversation meandered, and when the time seemed right, I asked if I might join her. She hesitated a moment, then said, yes, that would be pleasant. I had already established that I worked at the Guggenheim, which seemed to give me some kind of credibility. She was midway through her week in Venice, a gift from her parents for her thirtieth birthday. She worked as a lawyer in New Orleans, but had been educated at Harvard, so we could compare notes. It turns out she was from an old New Orleans family. She said Venice reminded her of New Orleans, with its decay, its mannered, byzantine society, its constant threat of flooding.

I was entranced. I made no moves, but offered to be of assistance in any way I could. She took my number, politely thanked me, saying she’d have to look at her itinerary and let me know. She allowed me to walk her to her pensione and shook my hand, looking directly into my eyes, as if I were a business acquaintance she was dismissing.

I walked home, vexed, sure I would not see her again. I suspected she had penetrated my veneer of respectability and had seen me for the cad I was. Unwilling to face my solitary room, I went to the neighborhood bar, hoping to catch some of the regular denizens with whom I might pass a few hours. But even the bar was strangely deserted and, glumly, I went to bed.

To my delight, Clothilde Soule did make that call the next morning. She was brisk and businesslike, but I didn’t let it put me off. We agreed to meet for a late coffee at the same trattoria.

It was a glorious morning. I sat outside waiting for her, watching the children chasing pigeons, the birds’ iridescent wings as glorious as any of Michelangelo’s painted angels. I inhaled the briny, slightly fetid air from the canal and braced myself to be disappointed by her in the unforgiving light of day. But when I saw her long legs strides over the canal bridge, her white dress floating around her, I was smitten all over again.

Never had I met a woman so reserved, so controlled, so matter of fact, so much in possession of herself! She sat across from me poring over travel brochures, entirely unaware of the effect she had on me. She looked up at one point, cappuccino foam gracing her upper lip, and without thinking, I reached over and wiped it off with my napkin. She looked surprised, but then laughed. I told her to put those brochures away and let me be her guide. She considered again—she seemed to be always considering—then smiled at me and agreed.

I couldn’t believe she tolerated my presence, and I found myself feeling like one of those over-eager American tourists. I sweated over where to take her, not wanting to waste a moment. That first day, I introduced her to my favorite haunts: the Palazzo Labia, Ca’ Rezzonico, hidden gardens I had access to. She preferred the late Renaissance to the eighteenth century, the Tintoretto’s to the Tiepolo’s, which heartened me. She took notes everywhere we went, so I was able to observe her as she studied the paintings, amused by her earnestness. She caught me out and looked cross, but I made some quip and she laughed. I felt as if I had won the lottery.

“Clothilde,” I finally said, “put away your notebook and just look!” She scowled, but did as she was told.

The next day, I persuaded the Walters to take us in their yacht to Murano, Torcello and Burano. Clothilde was delighted with the islands, with the brightly painted houses and their matching boats. The weather favored us, and the usually sober Adriatic splashed gaily as we docked. I was impatient to show her Tintoretto’s famous painting in the church of the Angeli, “The Finding of Saint Mark’s Body.” She kidded me for my saint’s name, and asked me if I could live up to it. I couldn’t, I assured her. She left the dim church in front of me, and seeing her long, graceful thighs through her thin cotton dress, the arc of her arm as she removed the lace kerchief from her head, I knew I didn’t want to try.

I had settled into an avuncular mode with her, being just enough older and just enough better traveled to take on that role. We sat on the dock waiting for the Walters to meet us, Clothilde propped up on her elbows, her body as relaxed as a cat’s, her head thrown back, her eyes closed. The sun hung on the horizon, bathing us in golden light. I inhaled her scent, the citrusy fragrance she wore, her own muskiness underneath, and watched a vein ticking in her neck. If I could put my head on her breast and listen to her breathing in and out, that would be all I would ever need, I thought. The water slapped against the pilings, echoing her breath. My longing for her stopped my own breath. Then her eyelids fluttered open and she regarded me levelly. I stared into eyes the color of the sun on the water, then hastily looked away, afraid she would guess my feelings.

The night before she departed, I took her to Osteria da Alberto, and ordered all my favorite dishes: squid marinated in balsamic vinegar; risotto of clams, tender and crunchy in all the right places; the sea bass, baked with mushrooms and herbs, so that the meat, while still moist, falls off the bone just so. You have to understand, dear friend, that Clothilde was at best an abstemious eater, yet I was able, that night, to get her to eat all courses, including a chocolate confection she ate in its entirety.

Yet as I walked her home, I became bereft at the thought of her imminent departure. I stood at the door of her pensione, flooded by a watery grief. I could not find my footing. I did not even try to kiss her, although she grabbed my hand warmly and kissed me on the cheek, then disappeared. We had arranged that I would walk her to the train the next day.

Confused and angry the following morning, I found myself acting like a surly fourteen-year-old, grabbing her bag brusquely, not answering her questions or responding to her observations until she repeated herself. I resented her for making me feel awkward and unsure of myself, as if she had purposefully played a trick on me. She seemed, as always, herself—pleasant, neat, unperturbed. At the train station, I negotiated her ticket in my poor Italian. With my back turned to her, I pondered how I had treated her better than I had ever treated a woman, and that she hadn’t really noticed.

I turned back to Clothilde. Her hair was down that day and a breeze blew it across her face. We stood on the platform as her train pulled up. She put out her hand and I took it and somehow we did not let go. “You will be late,” I said. “Yes,” she said.

Her train left without her.

Clothilde stayed in Venice an extra week, and I made arrangements to move to New Orleans as soon as possible. We had a church wedding at the cathedral, a High Mass. I converted. Not because I believed, but because it made Clothilde happy. She wore Burano lace.

I settled into the place comfortably enough, despite the fact that Clothilde’s father didn’t care for me. A sleek, successful lawyer, he would take every opportunity to stick it to me about my slothful ways, my habits of spending whole afternoons reading in the café. Clothilde told me not to take it personally, that he would have found fault with anyone she married. Besides, she said, she didn’t need me to make money. She was as driven as her father and made money as a matter of course, the way some people have a gift for language or a talent for sport. I still did translations in my desultory way, but Clothilde said she was happy to come home and hear about the people I’d met that day, the books I’d read.

She guided me through New Orleans as I had guided her through Venice, patiently explaining in a bemused voice about social aid clubs or jazz funerals that seemed to pop up out of nowhere, the musicians startling in their plumage. I missed Carnival in Venice, but it was more than made up for by my first Mardi Gras. I found it amusing that Mr. Soule the sober took it all so seriously, and I made the mistake one evening of making a joke about his membership in the Krewe of Comus, only to be given a wide-eyed look of horror by Clothilde. She would brook no jokes at the expense of her family, or her city.

The night of the annual ball, everything I thought I knew about this family seemed to shimmer and dissolve. As we gathered at the Soule mansion, I looked around at the strange masked creatures around me—Mr. Soule in green satin and strange pointed shoes, Mrs. Soule, no longer the quiet, retiring plump woman scurrying off to daily mass, but resplendent in golden taffeta, a tiara on her head, mysterious behind her feathered mask. And then there was Clothilde, my sweet, no-nonsense wife, draped in deep purple, diamonds at her neck and ears, her hair swept up elaborately, her eyes laughing at me behind her mask. As ridiculous as I felt in my rented tux and mask, as much as I wanted to poke fun at the whole business, I grabbed Clothilde’s hand and allowed myself to be swept away. We danced all night.

Except for Mardi Gras, Clothilde wasn’t much for playing. If I could get her in the right mood, plying her with whiskey sours, there was never a more enchanting companion.

We spent many long evenings that first summer gorging ourselves on oysters at Arnaud’s and crawfish étoufée at Brousard’s, on jambalaya at the Palace Café. We made a ritual of eating muffalatas at the Café Maspero every Friday. I’ve mentioned to you that Clothilde was by nature a light eater, but she indulged me then. She would have been happy staying home with grilled cheese, but I think she enjoyed “showing off” her city’s cuisine. Many nights we ended up at the Café du Monde, swigging cup after cup of the chicory flavored coffee, munching on beignets, walking hand in hand down Canal Street, as sated and content as two coddled cats.

It was on one of those nights, the air thick with heady scent of frangipani, the sweet notes of clarinets and pianos spilling into the streets, that we stumbled on a fortune teller. I had enjoyed generous libations, and when I saw the old black woman swathed in red reading palms, I couldn’t resist. Clothilde balked. I teased her, and she retorted that it was just a tourist trap, a sham.

“If that is the case, my dear, you have nothing to be afraid of,” I whispered in her ear, propelling her forward. “Come on, Clothilde, for fun.”

The woman read my palm first, telling me that I had a long life line, that I enjoyed the pleasures of life (that wasn’t a hard guess), but that I would be given a test. I laughed, feeling somewhat let down by the generic reading. I urged Clothilde on, hoping hers would be more interesting. I was half hoping for some insight into my bride, whom I found, even then, as elusive as the city she so loved.

Clothilde reluctantly held out her elegant, slender palm. The woman took it, peering into it, her face contorted in concentration. Then she looked up at Clothilde, her eyes wet, and pushed her hand away. She shoved the dollars I had given her back at me as Clothilde, her shoulders hunched in anger, stomped away. When I caught up with her, she was crying. “I told you I didn’t want to do it,” she hissed at me.

I grabbed her shoulders and turned her around. “I am so sorry….I had no idea.”

“Superstitious nonsense.”

“But, honey, if it is, then don’t be upset by it.”

“I’m just upset that I let you talk me into it. Don’t ever do that to me again!”

I couldn’t put the incident of the fortune teller, and Clothilde’s reaction, out of my mind. A rationalist, I have always supposed that fortune telling, voodoo and the like are clever devices used by the powerful to control the weak. Still, I found myself looking for the fortune teller in my rambles about the city. I never saw her again.

Yes, I walked everywhere, often ending up in one of many old cemeteries. They take their cemeteries seriously here. The elaborate above ground tombs and crypts remind me of Pere Lachaise in Paris. Evidently, these “cities of the dead” were built because the frequent flooding caused caskets to float away. You would think these places would be grim, but they are not. Planted with flowering trees and enclosed from the bustle of the city, they are actually quiet lovely.

Unfortunately, my interest in the cemetery became more than academic. Clothilde’s mother, Marie, with whom I had a warm relationship, became sick soon after we were married, and died not two years later. She was interred in the St. Louis cemetery Number Two, in the Soule crypt, and it was only then that I finally came to understand that I had married into one of the oldest and most prestigious families in New Orleans. Not at our wedding, mind you, lavish though it was, but at Marie’s internment. There was a jazz band, and a huge party afterwards, where no emotion was spared, nor any drink.

Clothilde was quite shaken by her mother’s death—an only child, her mother had been her best friend. But she had her work, and Clothilde was practical, able to compartmentalize if need be. Only I saw how grief-stricken she was. I must tell you, I was worried about her. She wandered around the house with a distracted expression. She lost weight rapidly. She had no appetite, and I found myself using all my ingenuity to get her to eat. Gone were our light-hearted jaunts around the city. Irritable and reclusive, it took everything in me to patiently coax her back to life.

Little by little, she began to improve. The color returned to her cheeks, and she allowed me to take her out one night for dinner. I held my breath that first night, afraid she’d wilt and ask to be taken home. But she didn’t. When she began noticing the bougainvillea, or peeking into a courtyard garden, my heart lifted.

We were almost back to our post-nuptial bliss when Katrina hit.

You’ve seen it all on the news, I am sure. There is not much to add. Mr. Soule summoned us on Saturday, August 27th. We sat in his den and watched the storm gather force, all of us fortifying ourselves with generous helpings of Old Grandad. Mr. Soule declared we were leaving. You know my love of storms, and my need to resist authority. However, I bowed to his demand for Clothilde’s sake.

As anxious as the old man was to leave the city, he was doubly anxious to return. As soon as possible, we caravanned back. The first thing that hit us was the fetid stench—the sweetish smell of rotting bodies, brackish water and acrid smoke, mold and fire. We passed block after block of gutted, burned, or smashed frame houses, the ones still standing all marked by the same high water marks. Furniture, clothes, and cars were piled outside houses, making the city as insubstantial as a refugee camp. The water hadn’t entirely receded; patches of standing water created the effect of a floating world. Looking into the oily black water of the canal, I saw the bloated body of dog swirl by, a child’s pink hat, tree limbs and unidentified detritus. We passed a rescue unit with a ladder up a tree. A dead black snake, half rotted, its skeleton sparkling whitely, hung like counterfeit Spanish Moss from an oak branch.

Mr. Soule’s mansion sustained almost no damage other than a few downed trees and minor roof damage. Our house, while still standing, was a different story. Mold covered everything—the walls, the books, the furniture. We spent the first few days back salvaging what we could and throwing away almost everything else. We had to stay with Mr. Soule while floors and Sheetrock were replaced. The work went on and on, and everything taking twice as long as estimated. Clothilde didn’t mind being home; we were in her childhood bedroom, white canopy bed and all, but I was anxious to get back to our own digs and my own routines—the café, the bookstore, the neighborhood that now was mine.

Finally, our house was ready. Although Clothilde was reluctant to leave her father, I think it was a relief to both of us to have our home back. That first night home, I bought a bottle of good champagne to celebrate. After the second glass, we kicked off our shoes, and by the third, we were dancing slowly to Coltrane’s “While my Lady Sleeps.”

Yes, we were happy to be alone together again. Still, nothing was the same as it had been. My collection of characters that I had met daily for coffee and a chat at our neighborhood café had disappeared, as if the receding waters had swept them away. The bookstore never reopened; when I passed the place it reeked, and all the ruined books had been hauled away. I was no longer content, as I had been, with my desultory ways. For the first time in my life, I volunteered—in soup kitchens, temporary clinics, schools. I heard stories of stunning loss, each one newly shocking. I realized then that I was not the world-weary man I had fancied myself to be, but a hopeless naïf.

We had only been back in our house a month when we heard a noise downstairs. Or rather, Clothilde heard it—she slept lightly. I sleep like the dead. All I know is that Clothilde in her can-do way, went down to investigate. I woke to the sound of gunshot. Half thinking it was a dream, I groped my way to the bottom of the stairs. Clothilde lay face down in her white gown, a red rose blooming on her back.

I won’t burden you with the details of the days and weeks after the shooting. Clothilde never saw her assailant. The bullet damaged her spinal cord; the prognosis was not good. The doctors told her she probably would never walk again. She became depressed and angry, and who could blame her? First her mother, now this. Her father wanted us to move back with him, but Clothilde, to my surprise, refused. Her father, it seems, took it upon himself to pay for more protection for us, for we suddenly had a security guard. I don’t know if Mr. Soule hired him for protection, or as a way to remind me daily that I had failed to protect my wife.

I can recount this to you, dear friend, now, somewhat dispassionately. But at the time I wondered what I was doing in this absurdist drama.

Clothilde took a leave of absence from work while she devoted herself to rehabilitation. The loss of her work was as devastating as her actual paralysis. I tried everything to make her feel less despondent, but nothing helped. She resented her loss of dignity when I lifted her onto the toilet or put her to bed. She resented that I could get out of the house, even if getting out of the house meant only that I was taking out the garbage or going to the grocery store. I had stopped my volunteer work in order to take care of her, but found myself missing it. At least other people’s stories were not my own. The air in the house was stale, smelling faintly of mold, and heavy with unhappiness. She was right, I would use any excuse to get away.

Yet when I took her for a “walk” on a good day, pushing her wheelchair outside, she seemed to only endure the outings. Some days I took her to our old haunts, to Audubon Park, which had survived surprisingly intact, or to City Park, but these outings took all my strength and there was no payoff. It seemed that Clothilde had resolved she would allow nothing to give her enjoyment, she would allow nothing to dilute her pure, freezing anger. It was the last thing that was hers; it was the one thing no one could take away.

I could not get her to eat, and her doctors warned she would not make progress if she didn’t eat properly. I made dishes I knew she liked, I brought her muffalatas, expensive cheeses and fruits, but nothing enticed her. It seemed to me she enjoyed, maliciously, refusing my blandishments. Finally, I lost my appetite as well. We resorted to canned soups and crackers, to protein drinks and vitamins. I had to measure her intake and outtake, to keep track of her bowel movements. I began to see the body—hers, mine, everyone’s—as a recalcitrant machine, not the fount of pleasure I had mistaken it for, and it horrified me.

Time seemed both in short supply and yet every moment was endless. Our days were consumed with “activities of daily living.” Just getting up, washed and dressed took forever. Clothilde was a small woman, but in her inert state, she was surprisingly heavy. My back went out lifting her from the bed to the wheelchair. She was catheterized, and I had to change her bag. Nothing got rid of the faint trace of urine in the house. Although I kept her washed, she smelled stale. Gone was her citrusy, musky scent. Most days I would sponge her down while she looked away, as if she could not bear to see me looking at her naked. Her shoulders collapsed forward, her small breasts sagged, the hair grew thick under her arms. She endured all my ministrations, complaining only if the water was too hot or too cold. It was as if she had vacated her body altogether, as if she had hidden herself away somewhere. I longed for any flash of life from her—even hatred for me would be better than this absence.

Clothilde, always so regular in her habits, wouldn’t let me wash her hair, no longer cared what she wore, never put on lipstick. Clothilde’s one vice had been her love of luxurious clothing; she had been as epicurean about clothes as I had been about food. One day I pulled out a black cashmere sweater I knew she loved and held it up. I told her how pretty she always looked in it, trying to tease out some spark of desire. She looked at me with exasperation, so that I felt like a child exposed in an elaborate and silly ruse.

“Mark, it doesn’t matter what I wear. No one will see me.”

“I will.”

She sniffed derisively, but put on the sweater, her eyes averted from me.

“You look great,” I said and tried to mean it, but the truth was that she looked gaunt and old, her face jaundiced.

“Will you stop,” she cried, and wheeled angrily out of the room.

I often had cabin fever.

I was no saint. I hated her sometimes, blamed her for her condition. I wanted the old Clothilde back, whole, naked, her elegant arms and legs wrapped around me. I stayed up nights looking at our photo albums, trying to imagine my way back to what we had felt for each other. And I did. With Clothilde in a drugged sleep in the next room, I would conjure up who she had been, who we had been. I could feel her hand in mine, smell her hair, see her laughing again at a joke. And I would believe it, only to be that much more shocked by the reality in the morning. Then the whole wretched routine began again.

I began to slip out of the house to score drugs, anything to relieve the boredom, anything to make me feel again. You know I’ve never felt any compunction about my recreational drug use. Yet for some reason, I began to. Even worse, I couldn’t find relief. For the first time in my life, I saw how easily I could become a junkie, and it scared me. It disproved everything I believed about myself. So, regretfully, I closed that door.

Instead, I found another addiction. I planned trips. Meticulously. Trips to Greece, Finland, Brazil, Thailand, New Zealand—I would get lost in research and then more research about a place, filling up notebooks with information, pictures, etc., half-convincing myself that these were real. I picked out accoutrement for each trip: cameras, shoes, backpacks, money belts, hats, a coat for Finland, sandals for Thailand, hiking shoes for New Zealand. I bought phrase books and CDs and learned enough of each language to get by. There was relief in that, in just the possibilities. It made the days’ routines less deadly.

Did I plan with Clothilde in mind? No, I did not. I wanted to forget about her, to remember what it was like to be free. And yet, at night, in my confused dreams, she was with me, whole, hiking a fjord, or walking through a Turkish bazaar.

We spent our days together, but every day we knew each other less. Our conversations— which had always been lively, easy, full of teasing, or heated exchanges of ideas—became merely exchanges of information: when the next doctor’s appointment was, had the insurance forms been filed, etc. Suddenly, I was in charge of all the quotidian details, wrangling with the insurance company, keeping track of the bills, cleaning the house. It was as if there was a ball of string to be untangled every day, and just when I thought I had it sorted, it would be a mess again. And it became apparent that I would have to find work soon, that between her loss of income and the medical bills, we would soon be broke. I talked with Clothilde about this, and she agreed. I was afraid that she would suggest we go to her father, but she didn’t, to my relief. As much as I hated work, I believed I had enough pride left not to be on the dole, especially his.

For the first time in my life, I was not able to magically procure employment. The art museum, universities and libraries were closed. What was needed in the city were strong backs and arms and I loathe physical labor. I ended up doing a patchwork of editing, writing and translating jobs via computer in order to be able to take care of Clothilde. I didn’t mind the work at all—most of it was tedious, but satisfying enough. It was the lack of colleagues I missed. Or maybe I just missed conversation, period. Clothilde now considered talking a waste of energy. Which was probably just as well.

After a year, it had become clear that Clothilde would never walk again. I thought she needed to go back to work, to have some diversion, but whenever I brought it up she looked at me with such a devastated expression that I backed off. She couldn’t bear for people to see her like this, she said, she couldn’t bear to be an object of pity.

I knew that decisions needed to be made, that I needed to think through what was happening to us, that this was not a life. But instead, I would pour a large Scotch and settle down in the evenings to YouTube travelogues.

Then, out of the blue, her doctor called to say that he had talked with a colleague in Dallas who felt that Clothilde would be a candidate for a promising new surgery. Clothilde took the call, and then handed the phone to me, her hand trembling. We looked at each other fully, perhaps for the first time since the accident. The air between us was thick with the questions and possibilities. There was some risk. It would be expensive. It might not work. But if it did? We could get back to what we had been. I thought of Finland. I thought of Greece.

I don’t know which of us was more excited as the date arrived. Clothilde became less resistant to eating, to washing. She even ordered some new clothes online. On the way to the airport, her hair in a French twist, her lipstick on, the air fragrant with bergamot, she said she was thinking of going back to work, one way or the other. I was stunned—and happy, knowing that work would stimulate her.

“Are you sure you are ready?”

“No, I’m not ready. I’ll never be ready to have people see me like this. I don’t want to be treated as a cripple. But we aren’t bringing in enough money.”

I felt myself blush. It was generous of her to say “we.”

“The operation may not work, Mark. I don’t want you to count on it.”

I glanced at her, surprised. “Me? What about you?”

“I want it, of course. More than anything.” She stared out the windshield, but I could see the moisture in her eyes. “You don’t have to stay with me, Mark. You don’t have to do this the rest of your life. My father will take care of me. I know this isn’t what you signed up for.”

I should have been relieved; I was being given an out. But I felt rejected, my pride hurt. I was angry and on the verge of ripping into her with,“ I guess you don’t like the quality of care?” or “do you really think so little of me?” but I didn’t. I held my tongue. She knew me so well. Of course she did. No, it wasn’t what I signed up for. I would never have called it so clearly myself. So, in a stab at levity, I said, “I could never leave you; we were married in the Catholic faith.” She turned to me then, a tear tracking slowly down her beautifully made-up face. She was not buying.

“I mean it, Mark,” and she fixed me with those toffee-colored eyes. She was back, my old Clothilde. A thrill went through me.

I wanted to protest that I loved her so much that I could not leave her. Yet, what she had released could not be put back in its cage. It seemed to settle in the seat between us, alive and muscular, that thing I had not wanted to look at. She was offering me my freedom, my chance to hike in New Zealand, to explore the Greek Islands. It was as if she had finally shaken herself out of her stupor and taking one long look at me, had unmasked my puny soul. Or else, she wanted one of us, at least, to be free.

I looked at her hollowed-out cheeks in the cold blue light of that early morning, at the tears silently sliding down them. She held her head very erect, and did not look at me. I thought of my first sight of her, of that same profile softened then by girlish roundness, and my heart twisted.

I pulled the car over, into a gas station, turned off the motor and pulled her to me.

She didn’t resist. I kissed her, realizing that it was the first time I’d really kissed her in months, and I was grateful for the tears, for the yielding, for the suddenly swirling waters we found ourselves in. I saw the two of us, holding each other on a roof or a floating piece of debris as the winds raged around us and the waters rose. Holding on for dear life.

Finally she said, “I can stand anything but the thought that you are staying with me out of duty. I can bear being crippled. But I can’t bear that.”

I licked the salt from the corner of my wet mouth. “I hate what’s happened to you, Clothilde. I hate it. I can’t stand what’s happened to our life.”

She patted her face, nodding, sighing noisily.

“And you know how bored I get, in the best of times.” She nodded again, and then the tears came again, quietly, steadily.

“It’s OK, Mark, I just want us to be honest with each other. That’s all.”

“I can’t leave you, Clothilde, and I don’t even know why. I want to leave, more than anything. But I can’t.”

She sniffed, patted her face with more wadded Kleenex she fished from her purse.

“I believe you,” she said finally, looking at me with her grave, direct gaze.

And I believed me too.

We arrived in Dallas with two days to spare, and we spent one at the Dallas Museum of art, where Clothilde couldn’t get enough. I wheeled her, unflagging, through the European and American collections. It was as if we were back in Venice, and I reminded Clothilde of how she’d teased me about St. Mark’s body. We had a superb meal that night, which we dubbed as the last supper, since she would have to fast before the surgery. It was as if we had been given forty-eight hours by some fairy godmother to be the Mark and Clothilde of old. We met with her doctors and when she went in for the surgery, I kissed her and squeezed her hand, whispering that this was only the beginning of the rest of our wonderful adventure.

The surgery lasted over eight hours. When the doctor came in and told me that it had been a success, I was ecstatic. She would be in recovery for about three hours, he said, then I could see her.

No one knew that Clothilde was sensitive to anesthesia. She died in recovery.

Mr. Soule and I buried her in the family crypt with her mother. The old man was inconsolable, but did me the favor of letting me know he did not blame me.

I took a job at the New Orleans Museum of Art when it reopened a few months later. Those early months passed like a dream. I couldn’t shake the belief that Clothilde was at home waiting for me, and I saved up small funny stories to tell her. Then I would walk into the house and be met by a loud silence. Slowly, I became accustomed even to that. I finally was able to bring myself to give away most of her clothes, although I kept a few pieces. Sometimes I sleep with them, inhaling her.

I still look at my travel notebooks, but strangely, I haven’t been moved to make any trips. I have colleagues now, and routines. I’m often invited to my friend Dave’s house, to be fed by his sweet, plump wife. I’ve come to be called Uncle by their pack of brats, if you can believe it. I go often to the “cities of the dead,” finding it consoling to visit Clothilde’s resting place. I bring one white Calla lily. They were her favorite.

I find, oddly enough, that I have never felt more alive.

Glad you found me, old friend. Do keep in touch.

Mark.