Chapter One

Arthur Millman wears the shadow of his mortality like a shroud, and I know that our time together will be brief but profitable. I give this commitment two months, tops.

Grey wisps of hair do nothing to conceal the marigold tinge of jaundice on Arthur’s scalp. Glee bubbles up in my heart. Pancreatic cancer is a hard-hearted mistress, and she has had her way with this thin, nervous man. While my latest client reviews the contract, I count backward. Diagnosis six months ago, followed by immediate surgery, only to find the cancer had metastasized. Two aggressive rounds of chemo, both unsuccessful, and here we are. I'm surprised Arthur has lasted this long—tenacious old bugger.

My contract is a beautiful piece of work, rows and paragraphs all lined up like little soldiers ready to secure my retainer. The legalese within was created for me by a hot young lawyer I dated for a few weeks. In essence, the contract says that I will be Arthur’s boon companion until his death and in return, he will guarantee my set fee, regardless of how much time is left until his eventual exit. There are caveats to cover all sorts of possible hiccups, such as the emergence of a heretofore-unknown heir, or death by misadventure—just because you’re terminal, it doesn’t mean you won’t get hit by a bus before nature takes its course—but it boils down to the simple premise that once Arthur signs, I am his for as long as he has left.

Frankly, the densely-worded document was the best thing I got from the relationship with the lawyer—her penchant for arguing got old fast. Sure, it was fun when she was debating who should be on top, but sometimes one just wants to have the last croissant without one’s lady friend launching into a full-scale court case about who has already had more than his fair share of pastries.

Arthur pushes the completed document toward me wearily, as though the mere act of signing his name has worn him out. I am relieved that this will be a short contract. Arthur is one of the least interesting people I've ever met—insurance adjuster by trade, dreadful bore by nature—but his foibles make Arthur an ideal client. What he lacks in personality, he makes up for in scrupulous financial management. His bank account is healthy and fat, the ironic opposite of the frail shell before me.

This first meeting in his generic one-bedroom apartment has been revealing. When I arrived an hour ago, I saw a sparsely decorated one-bedroom with cheap furniture, the sort of bulky garbage you might pick up at a big-box store if you were utterly devoid of taste or style. Arthur's apartment personifies the colour beige, save for a lone photo tacked to his bedroom wall. The image was the only blaze of colour in a wasteland of apathy: a Spanish señorita with a Carmen Miranda-style turban. Her red mouth was wide with laughter, and her lips shone as though she had just licked them.

“Friend of yours?” I had asked, knowing full well that a stunner like that wouldn’t pal around with Arthur if he were the last hombre on earth.

“It's a postcard,” Arthur said. He hitched up his sagging slacks. “My boss went to Cuba last year. He sent one to everyone in the office.”

“Must be a nice guy.”

Arthur frowned at the photo and tugged on his pants again. Did the man not own a belt? “I think he was just showing off,” he said at last. “The card's blank. Not even a 'Wish you were here.’”

An opportunity glittered like sunlight on azure waters. “You want to go to Cuba?” I asked. “Show the boss man he's not the only one who can eye up those chicas?”

Maybe this contract wouldn’t be so bad. Mojitos and cigars, Havana with her sultry, slutty nights and faded decadence, a week away from Vancouver’s drizzly skies and grey November days . . . even Arthur would be palatable under the Cuban sun.

Arthur looked embarrassed and cleared his throat, a wet, rattling sound that set my nerves on edge. His pale tongue snooped around the corners of his mouth like a blind worm. For a brief moment I wondered at his anxiety, but understanding soon dawned.

We were not going to Cuba.

My expression remained passive but inwardly, I sighed. How frightfully depressing for someone like Arthur to have such a predictable fetish. Still, I saw my opportunity to clinch the deal, so I anted up and went all in. Either I was right and the contract was mine, or I was way off base and likely to be shown the door. Difficult to say which outcome was preferable.

“Great dress she's wearing,” I said. "And those stockings! You imagine they would feel amazing against your skin.” I trailed a finger down the image wistfully.

Arthur's eyes lit up and he clasped his hands together in front of his thin chest like a kid on Christmas. Ladies and gentlemen, we have a creepy crossdresser bingo.

“It does feel amazing,” he said. He shoved his hands in his pockets to keep them from falling off. “I—I've always liked to wear ladies’ clothes. Just in the apartment, you know, and not every day. Only on Friday nights, with a glass of wine—a treat at the end of the week.”

“Absolutely. Sounds like a great way to unwind,” I enthused, all the while thinking that shoveling myself into a strapless number sounded like hell. I could only hope Arthur didn’t want me to play dress-up with him, because I don't have the legs for a slinky number like Miss Chiquita Banana.

Everything I needed to know about Arthur became clear. He would be my next client and more importantly, he would pay a premium for my services. Let me tell you about a guy like Arthur: he keeps his cross-dressing a secret and isolates himself, sure that no one will understand his proclivities. When a terminal diagnosis comes, any friends or family he might turn to have long ago vanished. He faces dying alone—and that’s where I come in.

Bring me your socially inept, your closet girlie-men, your assholes, and your lonesome-cat ladies. If they're terminal and they have money, they can retain my services as A Friend until the End.

Rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it?

It's a simple service, and yet one most people couldn't provide. For the last eleven years, I have contracted myself out to the dying to be their companion until they die. Whatever they want to do in their final days, I'm there to facilitate it. Last road trip? I'm your wheel-man. Want to swim with the dolphins? I'll corral Flipper myself. Looking for a final act of vengeance against an old business rival? I've got a trunk full of solutions and an active imagination.

When some people hear what I do for work, they think I'm a bottom feeder. Others believe I’m a sainted man doing God's work but the latter, when they hear my fee, tend to agree with the former. I take a broader view of the situation. Sure, it might seem callous to charge the dying for the pleasure of my company, but that doesn't factor in the immense comfort I bring them in their final months. The people I serve are not your typical jolly-grandfathers-with-oxygen-masks or pretty-despite-chemo-baldness soccer moms. Those peacefully terminal individuals have no use for me; a warm circle of family and friends will buoy them up as they ascend to the Pearly Gates.

My clients are degenerates who, often through some fault of their own, have found themselves alone at the end of their lives. These are the folks who ruthlessly trampled others on their way to the top, the self-involved creeps, and the blustering malcontents.

Some of them are like Arthur; not bad people, but odd enough that society treats them as modern-day lepers, as though weirdness were catching. A bad diagnosis comes, and they realize they will most certainly die without a familiar face at their bedside. Their final days will be spent with faceless nurses and preoccupied doctors, devoid of true human connection as they watch the clock wind down. Once the horror of that reality has set in, they find their way to me with wallets gaping wide.

I came to my profession as many do—by accident, and against my better judgment. It was at a support group for the recently bereaved, and I was there to mourn my mother. Or rather, to attempt to mourn my mother. My grieving was a work in progress.

A therapist I tried to pick up at the bar suggested I might be “emotionally blocked.” According to her, referring to your newly dead mother as “the heinous old bat” meant you weren’t moving through the grieving process in a healthy way. When I suggested she help me navigate my time of need on her therapy couch, she gave me a saucy grin, handed me a slip of paper with an address and a time, and said it would be worth my while to show up.

I was a sucker back then. I arrived, half-hard with anticipation, only to find myself in a dingy church basement with a bunch of sad sacks talking about their feelings. Turns out the sexy therapist was in the habit of sending her patients to that support group. I wilted. It was not the evening I expected, but they had donuts, so I stayed.

We sat in a circle on metal folding chairs, the fluorescent lights buzzing and pinging maniacally overhead, and we proffered our wounds for all to see. One guy talked about how lonesome he was without his wife; he couldn’t find his keys anymore, he said, and the azaleas in the front yard had died. Another woman went on for thirty-two minutes about how much she missed Uncle Kevin. Family gatherings just weren’t the same without Uncle Kevin. It was always Uncle Kevin who changed the oil in her car, and now her husband said they should just have it done at the shop. No one else seemed to miss Uncle Kevin the way she did. She wondered if her family members were jerks.

The night wore on with the litany of mundane things that people missed about their dearly departed, and just as I had begun to think the donuts weren’t worth it, my turn came. I gulped and laid a hand on my stomach, which was doing backflips. I hadn’t realized sharing was compulsory.

All weepy, red-rimmed eyes were on me as I said, “My name is Johnny. My mother died last week, and all I feel is relief.”

Uncle Kevin’s niece stared at me with a naked expression of disgust. The guy with the dead azaleas, and all the other bereaved, regarded me similarly, as though I had slapped them in the face with a week-old mackerel. The group leader, Bob, sought to salvage the situation. He gave me a sympathetic smile and said, “We all grieve in different ways, Johnny. Sometimes, when someone has suffered for a long time, we’re relieved that their pain has ended. Is that what you meant?”

“Nope, no suffering,’ I said. “She had a brain aneurysm in the middle of her weekly poetry club meeting. Rilke, some deep, insightful commentary, and then she shuffled off this mortal coil and went face-first into a bowl of onion dip.”

Bob, determined to see the good in me despite rumbles of discontent from the others, tried again. “When someone passes suddenly, it can be a shock. It’s completely normal for your emotions to get a little jumbled. Sadness will come, once the shock wears off.”

I should have let it go. There was no reason not to nod in agreement with Earnest Bob. I would never see these panty-waisted whiners again. Nobody would be hurt by a little white lie, but I couldn’t help myself. I was like a prisoner released after twenty-seven years inside. I wanted to caper about and roll in the grass, drinking deep from the fountain of my freedom. So I said, “Bob, I have to tell you, I feel like I’m on top of the world. A week ago, my life sentence was commuted. I’m so damn happy, I could kiss you. Were it not for your mustache, Bob, I might actually do it.”

The mood turned ugly in that dank basement. Bob wisely decreed that we should break for coffee and donuts. Finally, the donuts! I decided I was going to make a run for it after liberating a cruller or two, but I was intercepted by the guy with the dead flowers.

“You really mean what you said about your mother?” he asked.

Nothing to lose now. “I meant it. If you had met her, you’d understand.”

Mr. Dead Flowers mulled that over. With the simplicity of one stating a plain fact, he said, “You’re one cold sonofabitch.” His words were devoid of judgement and filled with grudging respect.

Quickly, I re-evaluated the man. While he had been moaning about his dead wife, he was as pitiful as the rest, but one-on-one, he seemed to be a brother. We were like two members of a clandestine society who meet on the street and wordlessly exchange the secret handshake. He saw in me what I recognized in him: a ragged hole where a conscience, an inborn belief in human goodness, is meant to reside.

Words spilled out of him in a torrent, like he couldn’t wait to be rid of them. “I cheated on her. Before we were married until the day she died, I was never faithful to my wife. I was in bed with the lady next door when she passed.”

I didn’t miss a beat. “At least you had someone to comfort you in your time of need.”

He barked a humourless laugh and shook his head. “My kids found out. They disowned me. They say I’m dead to them.”

While half-listening to Mr. Dead Flowers, I inched toward the donuts. Uncle Kevin’s niece had put away an alarming number of pastries in the time I’d been waylaid by the Confessional Casanova. With perfect clarity, I thought, “If this does not end in donuts, my night will be utterly wasted.”

Burgeoning unease about the cruller situation had diverted my attention, but I refocused in a hurry when Mr. Flowers said, “I have a business proposition for you.”

Thus began my career as a friend-for-hire.

Mr. Dead Flowers, real name Gerald Rogers, had testicular cancer. One side effect of that particular affliction was impotence. He seemed more pissed off about the loss of his manhood than the fact that he was dying. Gerald believed God was punishing him for his infidelities by making sure his last days were nookie-free and miserable. His kids still didn’t want anything to do with him, his former flames were not interested in playing nursemaid to a sick man, and friendship was a commodity in which he had never bothered to invest. Gerald spent his life chasing tail and, with his raison d’etre gone, the day had too many hours and not enough to fill them. That evening, Gerald came to the support group for the bereaved because he was lonely, and because they had better snacks than the support group for the terminally ill.

The proposition was simple. Dying alone was boring, Gerald said. He wanted someone to hang out with in his final days. He had considered employing a prostitute but decided it would just remind him of his decommissioned equipment. Spending time with a prime piece of ass when you were impotent was like going to a Vegas buffet and only eating salad. What was the point?

Gerald offered me five thousand dollars to keep him company until he died. He became my first client, and I honed my craft with that emasculated womanizer. We bet on the ponies, drank great scotch, and smoked fat, fragrant cigars until our heads spun. He told me about his greatest conquests, and I guffawed at all the right parts and slapped my knee until I was speckled with bruises. When Gerald kicked the bucket, it was with a smile on his face and a twinkle in his eye, which is more than he deserved, but exactly what he paid for.

He may have been a lecherous old coot with poisoned balls but, in his will, Gerald left me an extra ten grand. Fifteen thousand dollars richer, I had found my calling.

Arthur won't be as much fun as Gerald, but I've factored that into my fee. My billing rate comes down to a basic equation. The amount of time I estimate the client has left, multiplied by how little I will enjoy our time together. For someone like Arthur, the time remaining is short, but the few months we spend together might be filled with telling each other how pretty we look and calling each other “Sally.” This satin-swathed nightmare will cost Arthur fifty thousand dollars.

Monday is my first day under contract to Arthur, and it is spent watching television. Hour upon tedious hour of soap operas, populated by women with huge hair and men whose pained expressions suggest digestive troubles. Had I known soap operas were another of Arthur's passions, I might have upped my rate.

In his high, breathy voice, Arthur catches me up on who is sleeping with whom, who is back from the dead, and who has impregnated his step-sister. Twilight creeps in through the blinds and, as our first day comes to a close, I feel myself slip one day closer to my own death.

When I ask what's on tap for tomorrow, Arthur looks perplexed. As though it’s the most obvious thing in the world, he says, “We watch again. Tomorrow, Stefania is going to confront Michael about his affair with Gloria.” Arthur, who appears personally invested in this fictional relationship, is puffed up with righteous indignation on Stefania’s behalf.

Sweet baby Jesus in His sheep-infested manger! Not another day of soaps!

“Listen, Arthur,” I say, “if that's what you want to do, then that's the plan—but do you really want to spend your final days watching TV? Isn't there anything else you'd like to do?”

Lest it be thought that I am a complete heel, let this demonstrate that I do consider the best interests of my clients—particularly when what they want to do makes me want to gouge out my eyeballs. Arthur has spent a lot to retain me, and I want him to get his money's worth. I network through word of mouth referrals; I need clients to rave about how incredible their last days with me have been. No one is going to pay fifty grand for me to loaf about on his couch—except maybe Arthur, but that's only because he's not thinking big.

This is a problem I occasionally encounter with the dying. Logically, they know their time is nigh, but part of their mind can't comprehend that they will soon be gone. Think about it. The average person understands the abstract idea that he will one day expire, but death is beyond his frame of reference. The mind can't wrap itself around the notion that it will blink out of existence, so people don't go for broke. They live conservatively, floss, pay taxes, and look both ways before crossing the street. They survive, but many of them don’t really live.

In his final days, Arthur is behaving as though he has another twenty years of mundanity in his bland apartment. What he needs is a blaze of glory. Gerald showed me the value in living like every day was your last, particularly when it probably was. Ol’ Gerald knew death was around the corner, so he smoked, drank, and gambled like he was the Sultan of Ball Cancer Land. When he lost a towering stack of chips that made me go weak in the knees, Gerald only laughed. He made his peace with the Reaper breathing down his neck; his last few weeks were his blaze of glory, and Gerald went out on his own terms.

The wilted man before me is at a loss. Arthur knows he should want something but has kept his desires pent up for so long that he can’t remember how to achieve release. Arthur is the human equivalent of blue balls; he needs the right thing to push him over the edge. My thoughts fire rapidly.

He likes dressing as a woman. Why? Is it sexual? Does he actually want to be a woman? I hope it’s not the latter—Arthur’s remaining time is not long enough for a gender switcheroo. Still, Arthur’s cross-dressing seems as good a place as any to start.

I ask, “When was the first time you dressed as a woman?”

Arthur’s eyes slide sideways as the tips of his ears turn pink. He hasn't mentioned cross-dressing since our first meeting, aside from a few tentative remarks about the glitzy gowns worn by the soap opera ladies, but I sense that he has been waiting for me to broach the subject.

“I'm not here to pass judgement, Arthur,” I say. “You would not believe the things I've heard in my line of work. Getting fancied up once in a while is very low on the totem pole of things that will shock me.”

Arthur takes a deep breath and, haltingly, he tells me.

Arthur's father left before he was born, so it was always just him and his mother. In retrospect, Arthur supposes they were poor but, back then, he didn’t know it. His mother was a talented dressmaker, and she always had work. At night, in their little house, he lay on the living room floor and did his homework with the comforting whir of his mother's Singer sewing machine in the background. Each day was much like the one before it, quiet and reassuringly ordinary—until Friday.

Every Friday night, they went to the movies. Arthur came home from school to find his mother in a beautiful dress, lipstick on, smiling and swaying to the radio. She wore the pearl necklace her parents gave her for her eighteenth birthday, and the smooth, lustrous orbs were luminous against her pale skin. After dinner was eaten and the dishes were cleared, no matter what the weather, Arthur and his mother walked downtown hand in hand to see a show.

It was the highlight of the week. The time spent with his mother where she didn't look tired and wasn't hunched over another dress for some rich, faceless client, was priceless. On the walk home, she invented silly stories about characters from the movie, suggesting new endings and creating side stories that should have been told but weren't.

They stopped holding hands as Arthur got older, but the weekly ritual continued, year after year. As a teenager, each Friday evening, Arthur picked wildflowers from the roadside on the way home and shyly presented his mother with a bouquet. Her eyes sparkled when she received them; she pecked him on the cheek and called him “a perfect gentleman.”

Arthur knew it was a little strange, someone his age choosing to spend Friday night at the movies with his mother, but Arthur was an odd and reclusive boy who had trouble making friends. His mother was the only person who understood him and loved him despite his awkwardness. They were inseparable, and in their own small world, Arthur never felt like an outcast.

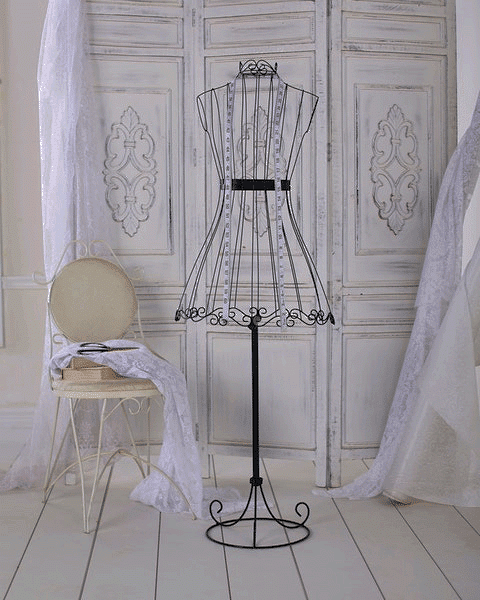

Their simple, unremarkable life came to an end one Friday in May. Arthur, age seventeen, came home to find his mother lying motionless on the floor. On the dummy was a finished dress; the hem fluttering in the breeze was the only movement in a room that was eerily still.

Frightened, Arthur touched her arm. It was stiff, rubbery. She was already cold.

“I don't know why I did it,” he says. “I guess I was in shock. I stripped down to my underwear in the middle of the living room, took the dress off the mannequin, and put it on. I never was particularly masculine, and even less so back then. Once I put on mascara, her red lipstick, and her pearl necklace, I didn't even look like me anymore. I looked just like a photo of her when she was nineteen, just before she met my father.”

The flowers Arthur had picked were wilting on the living room floor, next to his mother's body. Arthur filled a vase with water, retrieved the flowers, and arranged the blooms with care. Catching sight of himself in the hall mirror, he stroked the reflected curve of his cheek and whispered, “A perfect gentleman.”

“They said it was her heart—a pre-existing condition. The doctor called it a defect. I always hated that—them saying her heart was defective. It made her sound insignificant but, to me, she was the whole world.”

Hidden in the angular features of an old man, I glimpse the boy Arthur once was. An outsider, painfully shy, and his mother was his only source of affection and love. Finds her dead one day and can't stand being himself, so he becomes her, gets close to her in the only way left to him. He inhabits her, wraps the last dress made by her hands around himself like a cocoon. Arthur is a sad, strange caterpillar who dreams of being a butterfly.

A little too “Norman Bates” for my tastes, but I can empathize.

Mothers. They always find some way to fuck you up.