The 2024 presidential election’s over: I’m starting to sleep better again; my blood pressure is returning to normal. It didn’t surprise me that Donald Trump won the election; it just appalled me.

It didn’t surprise me that during the campaign, Trump supporters saw those of us that opposed his election to president as the enemy; nor did it surprise me that we saw Trump supporters as stupid, naïve pawns.

It did surprise me, though, to learn that my girlfriend was the enemy.

Okay, she isn’t my current girlfriend, but she was for a while after high school. And maybe “enemy” is a bit of an exaggeration. But she did vote for Trump! Twice! And posted pro-Trump, anti-Biden, anti-Democrat, anti-social-policy messages on her Facebook page! This kind of thing:

Democrats kill a bill for tuition assistance for children of veterans killed in battle, then approve giving illegals free tuition! Why? Because we’ve served our country to protect the nation they HATE?

How could I have misread such an important person from my youth? Ever since I found out, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around it.

We were good friends, Carrie and I, all through high school back in the ‘60s. She and my buddy Dave dated for most of that time, so we double-dated a lot and hung out in the same group of people. She was in the band, and we band folks were cliquish in our own way. I went to parties in her basement rumpus room; she hung out at my house.

The summer after graduation, she and I started hanging out more, going to movies, going for walks, listening to music. And then we were a couple. We got burgers, fries, and Cokes at Parkmoor and soft-serve ice cream at the DQ. We drove around a lot. And at night, when we got back to her house, we’d make out in the driveway until the porch light turned on, meaning that her father knew we were out there.

Then, Labor Day weekend came, and I went off to college. We wrote to each other a couple times a week—this was decades before email and cellphones, even before dorm rooms had their own phones—and ended our letters with “amor & osculations,” which we quickly started abbreviating “a&o” and which we both thought was extraordinarily clever and erudite. She came to campus once or twice, and I saw her a couple times when I went home for the weekend. Then, I met the woman I would later marry, Carrie started dating the guy that she would marry, and that was that. We stayed friends but saw and talked to each other less and less.

I ran into her a couple times after college, but that was decades ago. At some point, I wrote to her, said I was going to be in town for a couple days, and maybe we could catch up over coffee. She wrote back, up for it, but it never happened.

I’ve always had fond memories of her, though, and always hoped she was happy and doing well.

Which brings me back to the more recent past. And internet surfing. Because I’ve reached a certain age, I embrace my memories with gusto and wonder about people from my past:

- Whatever happened to Dick Baroody that lived next door to me on Dumbarton Rd. and moved away to some city whose name I can’t remember?

- Whatever happened to Betty Minder that I team-taught with in 1971?

- Whatever happened to that kid that never did his homework done but was the brightest kid in the class?

- Etc.

And during those pandemic-induced cabin fever days, I’d sometimes look on Facebook for answers to those kinds of questions.

And that’s how I found Carrie.

Over 3,000 Americans were killed [on 9/11]. Not by “some people” but by Islamic terrorists! This is how many muslums [sic] serve in public office [followed by a list of about 75 names and home districts]. How do you feel now!

Pro-Trump? Anti-Muslim? I couldn’t believe it. Where had she gone wrong? When and why did she veer off the Highway of Sanity onto the Road Paved with Hatred?

And then my brain suddenly screeched to a halt. And then I realized that we had never talked politics.

People think of the 1960s as being full of activism and political unrest. But that was the late 60s. This was the first half of the 1960s, when middle-class white America was still living in the afterglow of the quiet, boring Eisenhower era. It wasn’t until later, with the antiwar and the Civil Rights movements, that high school kids in my part of the world were aware of what was happening. It makes complete sense, then, that—other than the excitement of having JFK in the White House and the tragedy of his death—we white kids didn’t think about politics.

It was a shock to see those awful posts on Carrie’s Facebook page, I guess because I’d assumed that our politics, our values, our versions of the world back then had been pretty much the same. If they had been, then she was the one that changed. But what if that was a faulty assumption? What if we really did have different political and social values back then but just didn’t talk about them? What if we’d always been on different sides of that line and just hadn’t realized it? Or if we had been the same, maybe I was the one that changed. Or maybe we started out in the same place, but then the circumstances of our lives caused our thinking to diverge.

Confused by these questions I began contacting some old high school friends, and then other friends and acquaintances.

Almost all of them reminded me that one of the rules of etiquette in the 1950s and ‘60s was that “you don’t talk politics and religion!” It was a rule that existed to create and maintain civility in family and social gatherings. The currency of the land was politeness. Corollary rules included not making waves, not talking about income, not sharing personal information about relationships or most other things. It was more important to get along. It was only the outliers that talked about that stuff. Most people, at least on the surface, were full of sweetness and kindness and casseroles. It’s possible, then, and even probable that many of my friends’ families viewed the world in very different ways from each other’s and from mine; we just didn’t talk about it. Now, that rule of etiquette, like so many others, has pretty much disappeared, a result being that many more of our differences are out in the open.

My high school friend Tom reminded me that the southern Ohio community we grew up in was primarily working class, people who had lived through the Depression and World War II. They believed, he said, that despite the various safety nets created by FDR’s administration and the post-WWII GI Bill that helped returning veterans go to school, buy houses, and in other ways get back on their feet, that “if I succeed, it’s because I worked for it, not because someone or some government gave it to me.”

My friend Barry, who played sax in our high school band and point guard on the basketball team, reiterated that. He said he initially voted Republican when he turned twenty-one—that’s the way he was brought up; his family were all Republicans—but gradually became more independent, albeit still Republican, as he read more, moved from the suburbs into the city, and began to meet more different kinds of people. It wasn’t until much later that he started voting for non-Republican candidates. “It’s the Republicans that have changed,” he said. “It’s no longer that reasonable Republican party that we grew up with.”

Barry grew up in one of the larger Protestant churches in our community. He said his father always bought the already cooked hams for the annual church banquet from a restaurant downtown. And he said his father told him that if some of the women in the church knew that the hams were cooked by black people, they wouldn’t have eaten it. “But we didn’t consider ourselves racist,” Barry said, “because we lived in a segregated world and so didn’t have to deal with race in any significant way.”

Barry also asked, “Have you asked Carrie about it?”

Have I asked Carrie about it? No, of course not! That would mean connecting with her in some meaningful way after fifty-five years. I’m a conflict avoiding introvert: I don’t like calling Chewy.com to tell them they got my dogfood order wrong; I don’t like asking our neighbor if he can mow his grass before and not while our company is having dinner with us on our deck. And he says, “Have you asked Carrie about it?” He expects me to call or write to this woman out of the blue and tell her that her political and social values are abhorrent, and I want to know why?!

A political science colleague said that in the 1950s and ‘60s, the wealthy were paying substantial taxes, much of the money being used by Ike and JFK for infrastructure (the interstate highway system, airports, etc.) and middle-class growth. For better or worse, she said, Reagan reduced taxes in general, especially on the wealthy, and widened the gap between haves and have nots. She also reminded me that many blue-collar jobs have been eliminated due to technology, efficiency studies, and the increased dependence on a global economy, with many industries having moved to or been supplanted by those in other countries, taking the jobs with them. All of these things, she said, created fear among working class people that they were losing control of their lives.

My cousin Rick, the CEO of a large nonprofit, pointed out that for much of the 20th Century, because the Democratic Party generally supported labor unions that provided a more powerful voice for workers against management, union members tended to identify more as Democrats than Republicans. As the strength of unions has weakened, he said, that union-Democratic connection doesn’t count for as much.

“What did Carrie say?” he wanted to know...

My sociologist buddy Barb said that generally speaking, talented, curious people tend to leave their small towns in search of a wider range of opportunities. The people who remain depend on the old, comfortable systems. As the old ways have changed—factories close, small businesses are replaced by big box stores, mass media programming becomes more socially liberal, etc.—those people have felt more adrift, become more fearful for their survival, and look for a strong leader to take care of them.

Many social systems, at least male-controlled social systems, another sociologist friend told me, are built on a “pecking order,” a clear power structure, at least partly represented by the police and military, the people who can maintain and restore order. When we’re feeling out of control—for whatever reason, he said—It’s common to revert to childhood, wanting to be protected and taken care of by parents, strong father figures, God, the forces that we believe took care of us in the past. Now, he says, there’s a fear of loss, and Trump’s “Make America Great Again” made people hope for a return to those more comfortable days back in the ‘50s and ‘60s, where—and this is one of the implicit messages—there was white control.

Most of my high school friends—and most of my current friends, for that matter—went to college. And all of them agree that college changes you. It introduces you to a broader range of people, a broader range of reading material and information, and a broader way of thinking about and viewing the world and your place in it.

Patti said, “My whole family was Republican. I voted for Nixon twice. Mom didn’t want me going to grad school. ‘Will you still come and visit us?’ she asked. She was afraid of things she didn’t know; she was worried about what would happen to my life.”

“If college doesn’t change you, it didn’t do its job,” Mike said. “Even though I went to a conservative Christian college, I still saw diverse people and was exposed to courses that required thought.”

College had another impact on society, as well. It put people on career tracks. Barb the sociologist said that young men who, for whatever reason, didn’t go to college often saw the military as a way to train for a career. Further, college students generally had an easier time than non-college males in getting military deferments that often led to their not having to join the military at all. Over time, these factors widened the cultural gap between those who went to college after high school and those who served in the military.

Barb couldn’t believe I hadn’t talked to Carrie. “You really should ask her. I mean she’s the one you’re wondering about. So why not just call her or write her and ask!” she said. By this time, the idea of calling Carrie was no longer a smack between the eyes; it had been rolling around in my brain for a while now and was feeling at least somewhat less outrageous.

“Nazis used to call it ‘control of information,’” I read on Carrie’s website last summer. “Today, the liberals call it ‘fact-checking.’”

Tennis great and feminist Billie Jean King, reflecting on her legendary 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” match in which she beat self-proclaimed male chauvinist Bobby Riggs, as well as her later outing as a lesbian, said, “People get nervous when something’s unknown to them. We’ve got to get comfortable with being uncomfortable and need to reach out to people who aren’t like ourselves.”

A couple of my friends pointed out that most people tend to gravitate toward people they feel comfortable with, people who look and act like they do, people who share similar beliefs, attitudes, and values. Over time, they said, you forget that you’re living in a closed system and assume that everyone—at least “normal” people—sees the world the way you do.

“For better or worse,” Barry said, “we had to get the hell outta Dodge. Our high school was all white, so most of us had little if any firsthand knowledge of black people other than the occasional cleaning woman who seemed perfectly nice.” He said his dad told him that “‘if you get to know people one on one, you can like everybody.’ Now that the country is more socially, culturally, racially, and ethnically integrated, people are forced to be with other groups. For some of us, that’s been a very good thing. For other people, though, not so much: they’ve become more tribal and isolated, and that translates into us against them.”

My more philosophical friends said that culturally, we’re in an existential crisis. Every day, we’re getting an overload of information and opinion that challenges our long-held beliefs and values. Patti said that this fear for survival is especially true for conservative Christians who rightly or wrongly believed that as [white] Christians, if they followed the rules, they would be protected and saved. Now the country is 13% black, plus an influx of brown people from south of the border, as well as people from Middle Eastern and Asian countries that aren’t Christian at all. (The clear rise in antisemitism is further evidence of this Fear of the Other.) Change is far more rapid. “We’re frightened by our inability to cope with the rapidity of change in the Information Age,” she said.

It reminded me of those rat lab movies we saw decades ago in our intro psych classes and the professor’s subsequent explanation. Just as a lab rat will eventually go into the corner of its cage and put its paws over its head to try to separate from a situation it can’t control, he said, people often try to wall themselves off against their feelings of loss of control, over the lack of predictability.

So, I did it. Finally. I emailed Carrie to wish her a happy birthday (yes, I admit it; I still remember her birthday), and casually (I’d like to think of it as “deftly”) mentioned that I’d seen a number of posts on her Facebook page that surprised me and that I’d like to talk with her sometime about them, not to argue or try to change her mind, but to get a better sense of where she lives politically and how she got there. I closed the email “a&o, jon.” She wrote back almost immediately, said she’d be happy to talk, and closed with “a&o, Carrie.”

A few days later, I called her. After the requisite niceties—there was so much to cover about our pasts and our presents that we didn’t even try—we got to it. I reiterated that it appeared that we were pretty far apart politically, I was curious about whether one of us had moved and the other stayed in the same place, or if we’d both moved further from center, and I assured her that my purpose wasn’t to try to convince her that she was wrong or to argue about any of the specifics of her beliefs or Facebook posts.

She said her parents and at least one of her grandfathers were “diehard Democrats.” But at that time, she said, “Democrats were the working-class party. Now, it’s the Republicans,” and that since she lives in a working-class world, it makes perfect sense that she’d be a Republican. She said that as she’s gotten older, she’s become more outspoken about the rights of working class and everyday people. She said she knows that most politicians are rich, “but Trump has gone out of his way to help other people.” She said we need to protect traditional American values against people from within the country who want to subvert them and also from people from outside the country who want to come in and reap the benefits—at our expense—that we’ve worked so long and so hard to achieve. And finally, she said that except for becoming more outspoken about her views (she thinks older people have fewer filters and so tend to be more outspoken about many things; I agreed), she doesn’t think her basic political position has changed since she was old enough to have one.

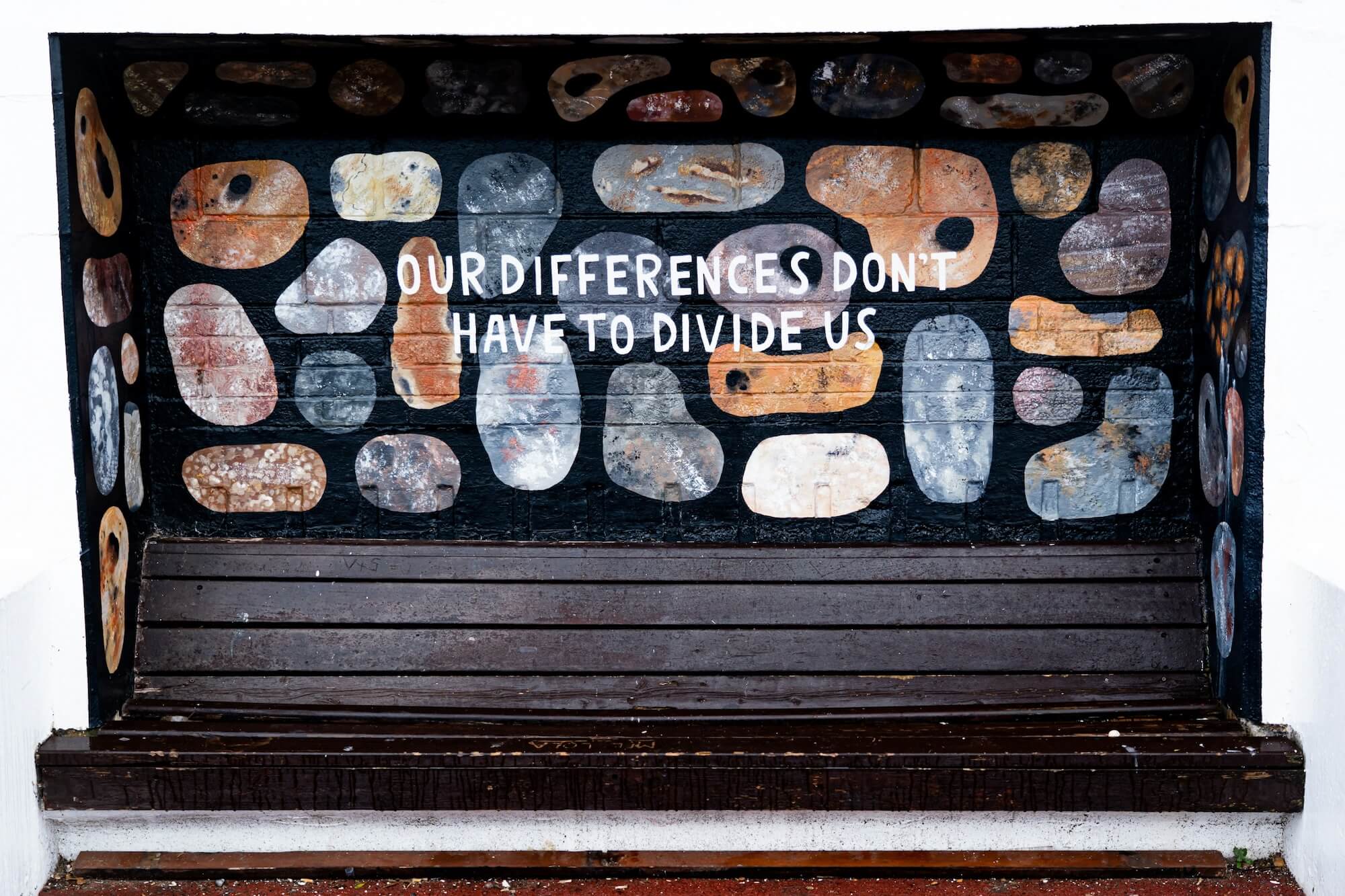

I started this rambling essay by describing my old girlfriend as “the enemy.” Maybe the real problem isn’t that she’s more conservative and I’m more liberal on the sociopolitical spectrum. Maybe the real problem is that I labeled her “the enemy.”

It reminded me of the Nathaniel Hawthorne short story “Young Goodman Brown,” in which a young Puritan man comes to believe that all of the people that he respected from his village—his teachers and clergy, the tax collector, his neighbors, even his wife—are in cahoots with the devil. As readers, we understand that he couldn’t see beyond absolute goodness and purity, that because everyone was imperfect, had made mistakes, had “sinned” in some way, they had given up their right to godliness and, therefore, by default, must be devil worshippers. And because he perceived them as “the other,” he died a lonely and bitter old man.

It reminds me of the Israelis and the Palestinians.

Once I see Carrie as “the enemy” or “the other,” the connections between us dissolve, replaced by barriers, our openness to consider and discuss other ideas, other styles, replaced by our need to attack the other or at least defend ourselves against that invading force. Talking with her on the phone and reading some of her nonpolitical Facebook posts (she continued posting pro-Trump, anti-Harris messages right up ‘til Election Day) reminded me that she was a nice person when we were in high school, and she seems to be a nice person now even if we disagree on some key values issues.

I also said at the beginning of this essay that “ever since I found out, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around it.” But why? Why does it matter to me? It certainly isn’t because I want to get back together with her as a couple. It isn’t even that I want to renew our friendship in any significant way. And although I thought it was just that I wanted to understand what accounted for that seemingly radical change in her and the concomitant gap that developed between our points of view, that isn’t it, either. Now, I think I do understand the reasons for that political gap, and it’s not enough.

I’ve read quite a bit recently about forgiveness. Do I need to forgive her? No. Does she need me to forgive her? No. So maybe it’s not about forgiveness, either.

So, what do I want? Maybe I want closure. Sometimes closure comes from “winning;” it can come from losing, too. Peace of mind? Maybe I thought that talking to Carrie would bring about some sort of resolution, that we’d have this deep conversation that got to the emotional and intellectual roots of our differences, and out of that would come understanding. But our conversation wasn’t like that. We didn’t go deep at all. She talked about her beliefs in a superficial way, and I didn’t push her beyond that. In all the years we were friends as teenagers, we talked about our friends and about movies and music we liked but never talked about religion or politics or family dynamics in more than a very superficial way. We’re not characters in a well-written novel or play, after all. We don’t go deep. I don’t know why I would have expected this phone conversation to be any different.

And where am I now? It’s been a long election season; I need to stop fighting; I need to rest. I guess I’m trying to make peace in my mind with Carrie, to accept the fact of our current (and maybe past) differences. We share a history, after all, not a present. I don’t have to like those political positions of hers in order to still have a residual fondness for her based on the years we did spend as friends. Maybe that’s the way I reconcile our conflicting beliefs and values and my conflicted emotions about them. And maybe that internal reconciliation is enough.